When the wind whips up the soil of the lakebed of the Salton Sea, now retreating due to ongoing drought, fine particulate matter sweeps through towns, under doors, and across playgrounds, bringing with it puzzling respiratory problems.

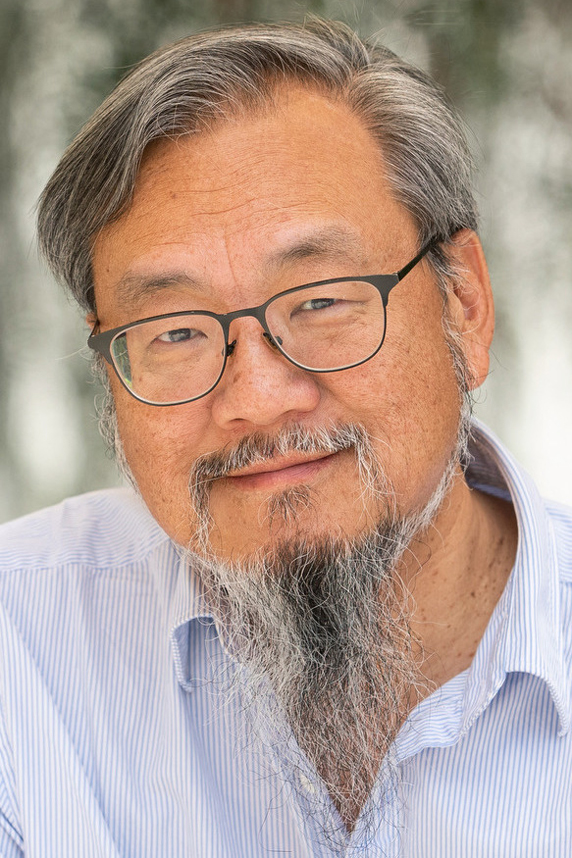

The mystery of whether aerosolized dust around the southern California lake is causing asthma and other health issues for nearby low-income and migrant communities was the subject of an Oct. 13 seminar by David Lo, M.D., Ph.D. His presentation was part of the NIEHS Division of Translational Toxicology (DTT) Seminar Series.

Lo is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences, and he received the Grand Challenges in Global Health Award from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. (Photo courtesy of David Lo / University of California, Riverside)

Lo is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences, and he received the Grand Challenges in Global Health Award from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. (Photo courtesy of David Lo / University of California, Riverside)Lo is a professor of biomedical sciences at the University of California, Riverside, where he directs the Bridging Regional Ecology, Aerosolized Toxins, and Health Effects (BREATHE) Center and the Center for Health Disparities Research which is supported by the National Institutes of Health.

According to Lo, it is clear that the Salton Sea is leaving behind aerosolized environmental toxicants as it recedes. His purpose in studying the health issues experienced by communities around the inland sea is to ask what in that mixture of left-behind pesticides, residues, decomposing organic material, and newly exposed microbial communities might be the culprit.

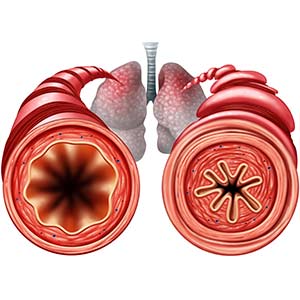

Chronic conditions

Lo is studying a form of asthma in children who live around the lake that is producing a chronic innate immune inflammatory response, rather than an acute response more typical of the disease. His working theory is that the health problems are caused by changes in the lake’s ecology and the resulting aerosolized material that becomes airborne as the lake recedes.

His research team collects dust and playa samples, either passively from what blows in the wind or by harvesting the dirt from the lakebed. Lo’s lab then pushes the particles through large environmental chambers fixed with baffles to ensure uniform distribution. Using a mouse model, the scientists measure exposure response over a four-week period.

They found that in tissues exposed to the Salton Sea dust, there was a spike in neutrophils, which are the white blood cells that are the body’s first line of defense. However, by day seven of exposure, that count dropped, and adaptive immune response was not triggered in the mice.

An aerial view of the Salton Sea and nearby agricultural fields. (Photo courtesy of Tim Roberts Photography / Shutterstock.com)

An aerial view of the Salton Sea and nearby agricultural fields. (Photo courtesy of Tim Roberts Photography / Shutterstock.com)“We assumed [reaction to the dust] to be an allergic, adaptive immune response,” said Lo. “Instead, it’s an innate inflammatory response. What do we attribute that to? The microbiome from the sea? Exposed playa? What materials are getting into the dust?”

Lo’s team is beginning a metagenomic study of different microbes found in the Salton Sea to better understand the concentration of pro-inflammatory components being inhaled by the residents. He hopes their research may lead to more focused way of diagnosing symptoms and a different kind of treatment regimen.

But beyond sampling and testing the dust, Lo’s team also needs better access to health data and to community members themselves.

“We need to understand not just their experience and how they identify associations, but also key into which symptoms we need to look at and how they relate to environmental conditions and clinical issues they face,” he said.

Overcoming challenges

It is difficult for the researchers to gain access to health data from members of the lakeshore communities. Many people who live along the Salton Sea are undocumented migrants of low socioeconomic status or members of Native American tribes, and they are wary of the scientists. There are also language barriers, and health care options are sparse unless families travel to the wealthier communities of Palm Desert and Palm Springs, north of the lake.

To overcome those challenges, the researchers are conducting a community survey to connect residents’ symptoms to exposures in the environment, with the eventual goal of empowering the community to be able to ask for the health care services they need from policymakers and health officials. They have held public forums and have even published a comic book to explain the connection between aerosols and asthma symptoms.

Community outreach combined with biomedical science is bringing the researchers closer to uncovering the mystery of the Salton Sea aerosols.

“Understanding the real-world and human context for the hazard assessments we do in DTT helps us optimize the human translational relevance of our research,” said DTT Scientific Director Brian Berridge, D.V.M., Ph.D. “Dr. Lo’s presentation and work not only help us understand the growing human health implications of climate change but also help us learn how people in affected areas are responding to unique environmental exposures.”

(Kelley Christensen is a contract writer and editor for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)