Electrically charging certain filtration materials can increase their ability to remove PFAS from water, according to Molly Frazar Lahey, Ph.D. The former University of Kentucky (UK) Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center trainee spoke about her doctoral research and unexpected career trajectory during the April 15 Karen Wetterhahn Memorial Award Lecture held virtually.

PFAS are a group of persistent compounds that are used in a wide variety of products, from dental floss to pesticides. Exposure to PFAS is linked to several harmful health effects, including diabetes, certain cancers, and liver disease.

“PFAS can leak into waterways from chemical plants or landfills, exposing people via drinking water or fish consumption,” said Lahey. “Recent regulation has set limits on PFAS in water, but we need a better way to remove these chemicals from contaminated water sources.”

Activated carbon filters are commonly used to remove PFAS and other chemicals from water. However, these filters lose their absorption abilities over time and need to be heated to high temperatures to restore them, which is costly and difficult. As a result, used filters often end up in landfills.

Charging forward with hydrogels

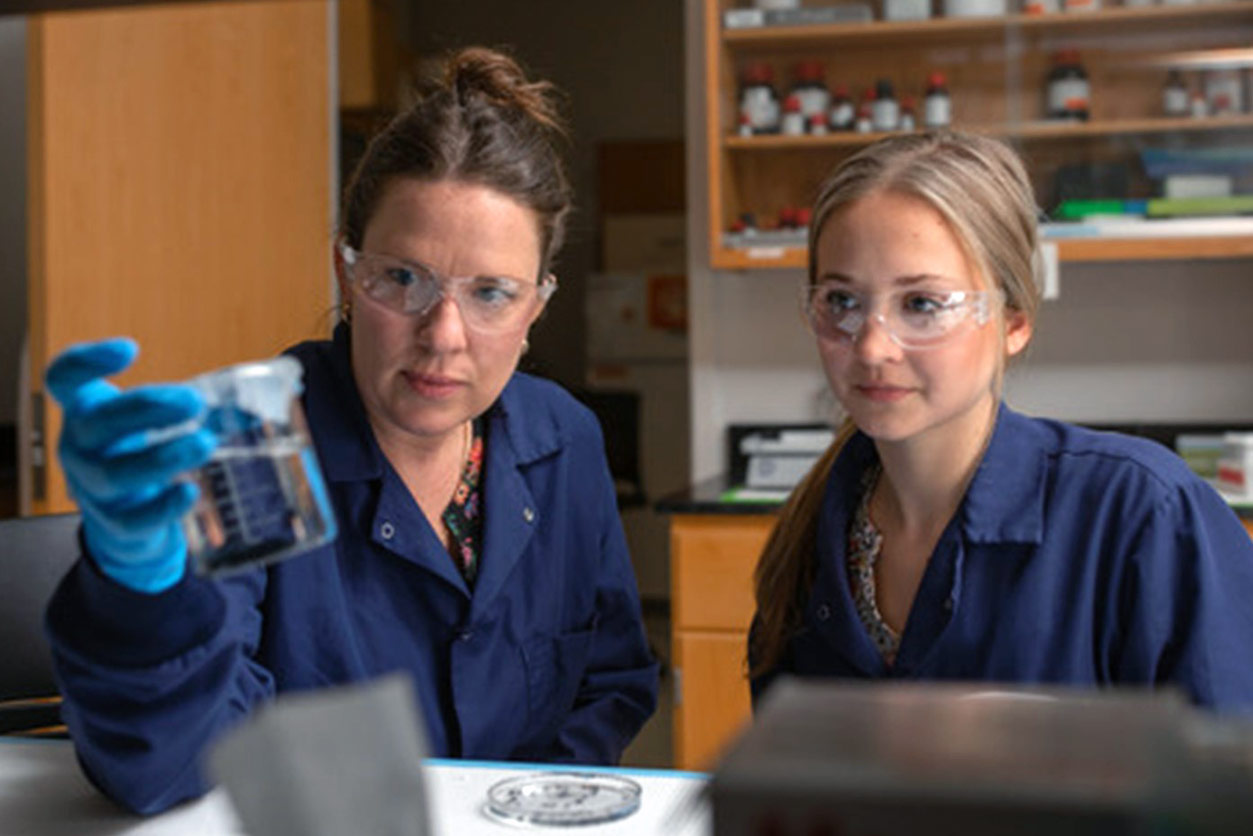

Lahey developed a low-cost filter using hydrogels — a water-absorbing material made from long chains of molecules, or polymers — that can absorb PFAS from water.

“PFAS molecules contain a group of negatively charged atoms, which can be attracted to molecules with positive charges,” said Lahey. “I hypothesized that, if the hydrogels could stay positively charged, even in various pH conditions, they could selectively attract PFAS molecules and contain them.”

She created hydrogels with positive molecules embedded into the polymers. Then, she tested their ability to remove PFAS from water samples collected from contaminated sites in Kentucky. Lahey found that the charged hydrogels absorbed almost all the PFAS in the samples. In some cases, the hydrogels can be regenerated to their original state by heating them with a specialized magnetic field.

“The charged hydrogels could remove the majority of PFAS in a sample in about two hours, much more quickly than activated carbon, which can take 40 to 60 hours to achieve similar results,” said Lahey. “If deployed as part of PFAS remediation plans, these charged hydrogels could be a lot more efficient than existing methods.”

From remediation to rockets

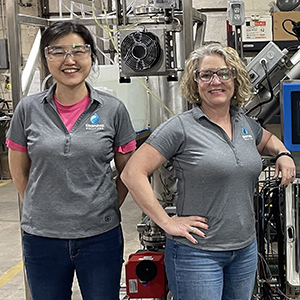

Lahey’s career trajectory took an unexpected turn after she received her doctorate. Boeing hired her to support development of the Space Launch System (SLS) for the Artemis program, NASA’s mission to return people to the moon for the first time in 50 years.

UK SRP gave her the confidence to make such a drastic career change, said Lahey. After working at Boeing for five months, she was promoted to lead the contamination and cleanliness control group, which ensures SLS hardware meets strict cleanliness requirements to prevent damage.

“My leadership experience at UK SRP is one of the reasons I threw my hat into the ring for that position,” said Lahey. “Now, I’m leading the group and I love it. I couldn’t be happier with where I am in my career right now.”

(Michelle Zhao is a science writer for MDB, Inc., a contractor for the NIEHS Division of Extramural Research and Training.)