A paternal high-cholesterol diet leads to fatty plaque buildup inside the arteries of female, but not male, offspring, according to an NIEHS-funded study in mice. The study, published Sept. 10 in the journal JCI Insight, sheds light on the role paternal exposures play in offspring health.

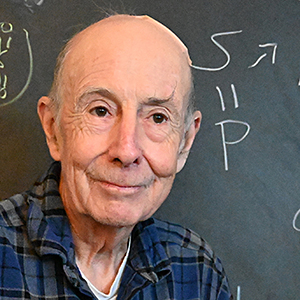

“A father's unhealthy eating can lead to heart disease in his daughters later on,” said senior study author Changcheng Zhou, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical sciences at the University of California, Riverside.

The findings prompted Zhou to offer the following advice. “Men who plan to have children should consider eating a healthy, low-cholesterol diet and reducing their own cardiovascular disease risk factors,” Zhou said. “These factors appear to affect their sperm in influencing the health of their female offspring.”

Intergenerational inheritance

Atherosclerosis is a complex condition characterized by the accumulation of cholesterol in large arteries, leading to plaque development (see sidebar). Despite major advances in diagnoses and treatments, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is still the leading cause of death worldwide. Although many modifiable risk factors such as smoking, diet, and obesity are well known to contribute to atherosclerosis, genetic and epigenetic factors can also increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

Previous studies have suggested that paternal factors affect offspring metabolic health, but there has been a lack of animal studies investigating the effect of paternal diets on offspring heart health.

“Most studies in the field have focused on the effects of maternal factors,” Zhou said. “The impact of paternal exposures on offspring health is poorly understood.”

Sex-specific transmission through sperm

To fill this knowledge gap, Zhou and collaborators investigated the effects of paternal high-cholesterol diets on offspring atherosclerosis development in mice. They found that this diet increased atherosclerosis and stimulated atherosclerosis-associated genes in female, but not male, mice. The researchers also identified two potentially novel genes called Ccn1 and Ccn2 that may contribute to increased atherosclerosis development in female mice.

“This study adds to the mounting evidence that demonstrates a parent’s environmental exposures, lifestyle choices, or genetic factors before conception can influence the health and development of their offspring,” said Thaddeus Schug, Ph.D., a health scientist administrator in the Population Health Branch at NIEHS. “In this case, daughters born to males who ate an unhealthy high-cholesterol diet had increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Importantly, Dr. Zhou and his team were able to show that unhealthy dietary factors can alter small RNAs in sperm, and these changes can be passed onto the offspring.”

According to Zhou, future research will focus on understanding how the sperm small RNAs mediate this intergenerational inheritance, and why only female offspring are affected with cardiovascular disease.

(Janelle Weaver, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)