Environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs) may reduce people’s ability to fight respiratory infections, according to Stephania Cormier, Ph.D., of Louisiana State University (LSU). Cormier, director of the LSU Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center(https://tools.niehs.nih.gov/srp/programs/Program_detail.cfm?Project_ID=P42ES013648) spoke to NIEHS on March 31, as part of the Keystone Science Lecture Seminar series.

Cormier studies how pollutants lead to cellular and molecular changes important in respiratory disease. (Photo courtesy of LSU SRP Center)

Cormier studies how pollutants lead to cellular and molecular changes important in respiratory disease. (Photo courtesy of LSU SRP Center)“Dr. Cormier studies whether exposure to early life environmental factors can predispose people to respiratory disease,” said NIEHS Health Scientist Administrator Danielle Carlin, Ph.D., who hosted the talk. “Ultimately, this research may lead to novel interventions and therapies to prevent disease.”

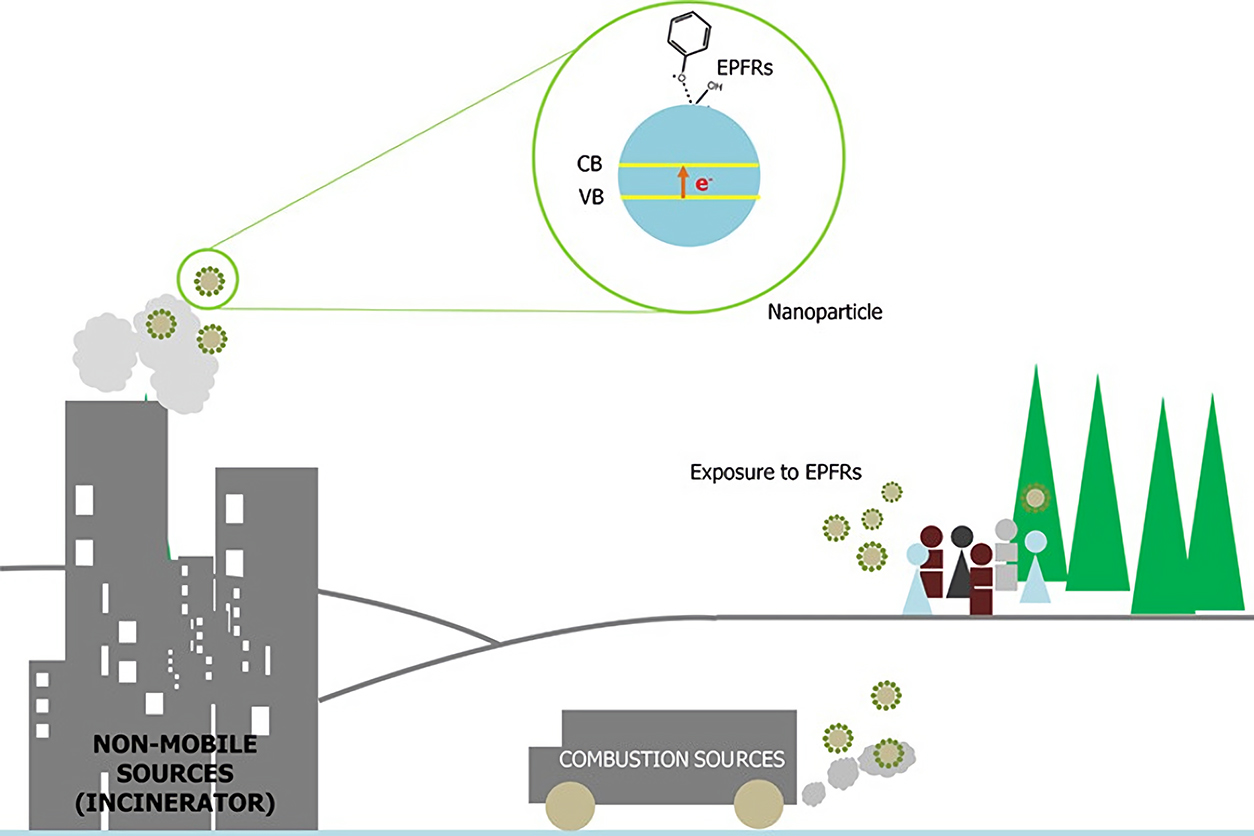

EPFRs, a relatively recently recognized class of contaminants, are generated when hazardous wastes are combusted or thermally treated. The compounds form when byproducts of organic material combustion interact with metal particles, such as copper or iron. EPFRs are highly stable and persist in the environment for weeks and even months.

“EPFRs represent an unidentified threat,” said Cormier. “While we know they may be present at a Superfund site, we may not know if they are present at a nearby community, or even in someone’s backyard.”

Since 2011, studies by Cormier and her team have uncovered important information about how EPFRs may harm health, including possible effects on the heart and lungs.

About 30% of Superfund sites use thermal treatment for waste disposal waste, which might explain why significant amounts of EPFRs are found at Superfund sites and in nearby communities. (Reprinted with permission from Vejerano EP, Rao G, Khachatryan L, Cormier SA, Lomnicki S. Environmentally persistent free radicals: insights on a new class of pollutants. Environ Sci Technol 52:2468–2481. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.)

Early life vulnerability

According to Cormier, every year nearly two million people die from acute respiratory tract infections as a result of air pollution. Children under the age of five are particularly vulnerable. “Children’s immune systems and lungs are still developing, which means they respond to air pollution differently than adults,” she said.

In animal studies, Cormier observed long-term negative effects on lung function after early life EPFR exposure. Such changes may result in more severe respiratory disease. In infant mice exposed to EPFRs, Cormier and team saw a dramatic increase in mortality after infection with the influenza virus. They observed a decrease in the abundance of cells critical to immune protection in the lungs of EPFR-exposed mice, which lowered their ability to defend against influenza virus.

Strengthen immune response

Carlin noted that Cormier has been a key member of the LSU SRP Center for nine years and has served as the center’s director since 2014. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Carlin noted that Cormier has been a key member of the LSU SRP Center for nine years and has served as the center’s director since 2014. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)Cormier also discussed strategies to protect against the effects of air pollutants on respiratory infections. For example, she and her team are looking at ways to encourage the body to produce IL22, a protein critical for developing immune responses to stressors, like pollutants and viruses.

“We saw an increase in IL22 immediately after exposure to EPFRs, meaning the lung was trying to repair itself,” she said. “After flu infection, the mice failed to make this protein. But if we can add IL22 to the organism, we can reduce lung injury and improve survival.”

Community EPFR measurement

“We are also studying a cohort of children from Memphis [who were] exposed to EPFRs, to explore whether air pollution increases the risk of developing respiratory diseases like pneumonia,” said Cormier. She and her team looked at visits to the emergency department, admission to the emergency unit, and length of hospital stays to identify communities with the highest burden of pneumonia.

They also worked with the local community, including school kids, to collect air pollution measurements across Memphis. Cormier and her team observed clusters of children with pneumonia in North and South Memphis, two areas of the city where the highest concentrations of air pollutants, including EPFRs, were measured.

Cormier stressed that the existence of EPFRs represents a new paradigm for evaluating toxicity of hazardous waste, and she pointed to the need to change monitoring practices so they include these contaminants.

“The interdisciplinary nature of the NIEHS SRP is tremendously valuable as we work to address this problem. By bringing people together who normally wouldn’t collaborate, we’re able to reveal new insights at the molecular, cellular, individual, and population levels that can help identify real solutions,” said Cormier.

Citations:

Lee GI, Saravia J, You D, Shrestha B, Jaligama S, Hebert VY, Dugas TR, Cormier SA. 2014. Exposure to combustion generated environmentally persistent free radicals enhances severity of influenza virus infection. Part Fibre Toxicol 11:57.

Jaligama S, Patel VS, Wang P, Sallam AA, Harding JN, Kelley MA, Mancuso SR, Dugas TR, Cormier SA. 2018. Radical containing combustion derived particulate matter enhance pulmonary Th17 inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Part Fibre Toxicol 15:20.

Vejerano EP, Rao G, Khachatryan L, Cormier SA, Lomnicki S. 2018. Environmentally persistent free radicals: insights on a new class of pollutants. Environ Sci Technol 52(5):2468–2481.

(Mali Velasco is a research and communication specialist for MDB Inc., a contractor for the NIEHS Superfund Research Program.)