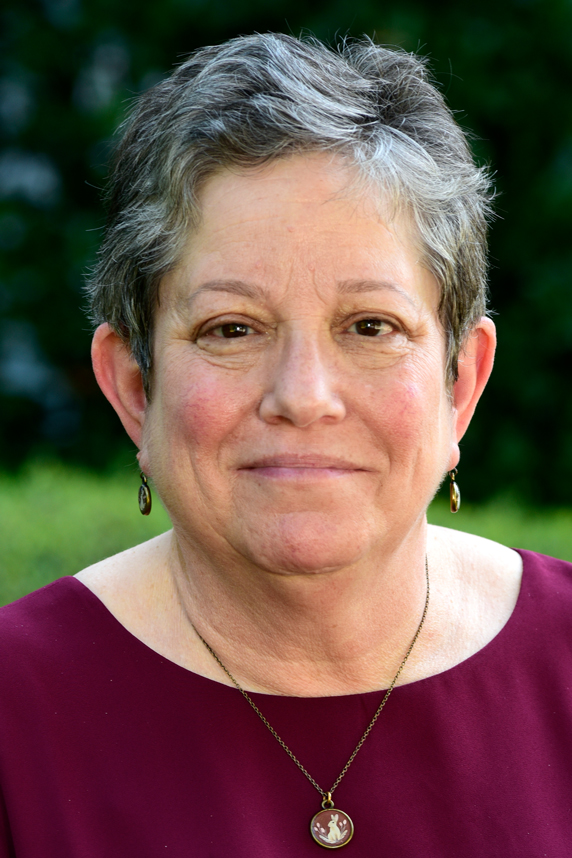

Dori Germolec, Ph.D., once could have been found lying among the ground foliage at the Duke Primate Center watching lemurs eat plants, marveling at whether the newly released animals knew which plants were toxic and which were safe to eat. Today, she looks beyond animal models for scientific discovery and explores new methods for studying toxicology, or the human health effects of potentially toxic exposures.

Environmental Factor recently sat down with Germolec to learn more about her scientific journey and her work to establish scientific confidence in new approach methodologies (NAMs).

Environmental Factor: How did your scientific journey begin?

Dori Germolec: For my master’s project, which was my first publication, I watched what lemurs ate after being newly released into an enclosure in Duke Forest, and then I collected those plants. I conducted chemical analyses to see the kinds of things, whether harmful or safe, that were in the leaves. That was my first exposure to toxicology. I got involved in immunology before that when I worked as a research technician in an immunology lab at the Shriners Hospital in Galveston, Texas.

I ended up marrying the two and working in an immunotoxicology lab at NIEHS. After I earned my doctoral degree, I became group leader of the Environmental Immunology Laboratory, where I supervised postdoctoral fellows, technicians, and students investigating the effects of environmental, industrial, and pharmacologic agents on the immune system.

EF: How has science evolved during your journey?

DG: We have transitioned away from projects that simply present toxicities and then record the immune response. For screening studies that we now do, we look at the effects of chemicals on certain aspects of the immune system. Having a research lab allows us to understand the biological mechanisms underpinning adverse effects.

EF: How are you reshaping immunotoxicology today?

DG: I have two main foci in my daily work as an immunology discipline leader and toxicologist in the NIEHS Division of Translational Toxicology [DTT] and the National Toxicology Program [NTP].

I am a project officer on an interagency agreement with the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), in which we are examining the potential effects of mold exposures. In collaboration with the project lead, Tara Croston, Ph.D., we are looking at general toxicology, neurotoxicity, and cardiovascular toxicity as well as the immunology, which Tara and I share as a research interest. In the DTT, I oversee contract laboratory research specific for immunotoxicology. So, I am still involved with the research, but instead of working in the lab, I direct the research based on DTT programmatic needs.

The second focus of my work is the development and application of alternative methods for immunotoxicity screening. When Brian Berridge, D.V.M., Ph.D., joined NIEHS, there was a programmatic shift toward using more translational and human-relevant methods. Immunotoxicology had already been at the forefront of this with the development of alternative methods to evaluate whether chemicals have the potential to cause skin sensitization [i.e., allergy]. I feel like that was one of the earliest and most prominent application of NAMs.

Although I was not personally involved in the development of any of those methods, we did lead a large effort to apply them. Working with NTP partners, we looked at how the test methods would work with mixtures and complex chemicals. We evaluated NTP chemicals that we had done in vivo [animal] screening for and applied in vitro [cell-based] screens to look at whether these compounds had the potential to cause allergic responses in the skin, and to help establish scientific confidence in those methods.

EF: When you look back over these four decades, which accomplishments do you feel are your biggest contributions to science?

DG: I feel like the shift toward the alternative methods in immunotoxicity testing will be my biggest scientific accomplishment. It is not complete yet, but I really feel like the transition away from the standard laboratory animal assays and the move towards being able to better predict in a more human-relevant model is something to which I am immensely proud to have contributed.

I am now part of a research group that is looking at the development of alternative methods for screening for developmental immunotoxicity. We hosted several workshops and have another coming up in May. Again, the idea is to foster the implementation of alternative methods to be able to screen for developmental immunotoxicity. It is really, I think, the way of the future, and it will allow us to be more mechanistic, more human-relevant, and more predictive.

EF: What is next?

DG: We are working on establishing scientific confidence in other NAMs, and we are developing an in vitro screening panel to look at immune suppression, not using experimental animals. Our work through the NTP Interagency Center for the Evaluation of Alternative Toxicological Methods recently resulted in a large-scale partnership with other federal agencies and commercial product manufacturers to explore some of the newer alternative methods to detect chemicals that can cause allergic reactions in the skin.

Allergic responses from skin exposure is one of the most common occupational illnesses. Evaluation of whether cosmetics, pesticides, or industrial chemicals cause either allergic or irritant responses in the skin is a major testing requirement in all countries. It is a significant problem in the general population, but hard to accurately measure just how much because it is difficult to distinguish between things that cause true allergy or just irritate the skin based on self-reporting and without specific tests. Respiratory allergy can manifest as something as simple as a runny nose or as severe as asthma and anaphylaxis. We try to predict which chemicals may induce allergic responses so that we can eliminate or minimize such exposures.

We have tested chemicals using in vitro methods and then compared that data with information on known skin sensitizers in humans to establish scientific confidence in those methods. Some of these methods are based on gene signatures — they use a specific set of genes to predict skin sensitization. In a new project, we are using a similar platform to evaluate potential respiratory sensitizers.

Citations:

Anderson SE, Meade BJ. 2014. Potential health effects associated with dermal exposure to occupational chemicals. Environ Health Insights 8(Suppl 1):51−62.

Strickland J, Truax J, Corvaro M, Settivari R, Henriquez J, McFadden J, Gulledge T, Johnson V, Gehen S, Germolec D, Allen DG, Kleinstreuer N. 2022. Application of defined approaches for skin sensitization to agrochemical products. Front Toxicol 4:852856.

(Jennifer Harker, Ph.D., is a technical writer-editor in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)