Researchers funded by NIEHS reported that inhalation of the widely used pesticide paraquat reduced the sense of smell in male mice for several months after exposure. Moreover, the chemical entered the brain and other tissues. These results underscore the importance of studying effects of inhalation of neurotoxicants, to protect public health.

Loss of sense of smell, or olfactory impairment, is an early sign of Parkinson’s disease. The findings, published Dec. 29, 2020, in the journal Toxicological Sciences, suggest paraquat may contribute to such neurodegenerative diseases.

A farm worker sprays a mist of pesticide in a rice field. Rice is one of the crops on which U.S. farmers use paraquat. (Photo courtesy of Kanokarn K / Shutterstock.com)

A farm worker sprays a mist of pesticide in a rice field. Rice is one of the crops on which U.S. farmers use paraquat. (Photo courtesy of Kanokarn K / Shutterstock.com)Direct path to the brain

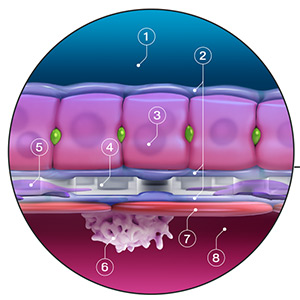

Researchers at the University of Rochester modeled inhalation of low concentrations of paraquat. Using the university’s Inhalation Core facility, they exposed mice to aerosolized paraquat. Then the team measured levels of the pesticide in lung, kidney, and four regions of the brain — olfactory bulb, striatum, midbrain, and cerebellum.

Anderson said that the potential for paraquat to be inhaled and then impair smell or contribute to neurodegenerative disease needs more attention by scientists. (Photo courtesy of Steven Brown, University of Rochester Medicine Web Services)

Anderson said that the potential for paraquat to be inhaled and then impair smell or contribute to neurodegenerative disease needs more attention by scientists. (Photo courtesy of Steven Brown, University of Rochester Medicine Web Services)“Inhalation can provide a direct route of entry to the brain,” explained first author Timothy Anderson. “If you inhale something and it goes into your nose, it can actually enter the neurons responsible for sense of smell, and travel into the brain.” Anderson is a graduate student in the University of Rochester lab of Deborah Cory-Slechta, Ph.D., where the study was conducted. Cory-Slechta is deputy director of the university’s NIEHS-funded Environmental Health Sciences Center.

Co-author Kevin Welle measured the highest brain levels in the olfactory bulb, suggesting paraquat entered the brain through nasal-olfactory neurons.

“The sex-dependent olfactory impairment observed after paraquat [PQ] inhalation exposure is intriguing and parallels important features of Parkinson’s disease [PD], including early loss of sense of smell and greater prevalence in males,” said Jonathan Hollander, Ph.D., health scientist administrator in the NIEHS Genes, Environment, and Health Branch. Hollander oversees research grants for neurodegenerative diseases and other areas.

“Given that paraquat is a known risk factor for PD, and inhalation is a prevalent source of exposure, this study may lead to a more useful animal model of PQ-induced neurodegeneration,” he added.

Males-only impact

Intriguingly, of the mice exposed to paraquat, only males failed to discriminate between scents afterwards. “These findings correspond to the fact that Parkinson’s disease is far more prevalent in males, and olfactory impairment is one of the early manifestations of the disease,” said Cory-Slechta.

Cory-Slechta was named the 2021 Distinguished Toxicology Scholar by the Society of Toxicology. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Cory-Slechta was named the 2021 Distinguished Toxicology Scholar by the Society of Toxicology. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)The scientists observed that olfactory impairment persisted as many as 200 days after exposure ended — even though paraquat was no longer detected in brain tissue.

Pesticides, loss of smell, and Parkinson’s

“There have been many epidemiological studies that directly implicate pesticides in the development of Parkinson’s disease,” said Anderson. “These findings have been supported by rodent studies, where an acute exposure to paraquat leads to hyposmia and other symptoms consistent with Parkinson’s disease.” Hyposmia is the loss of some or all of the sense of smell.

Pesticides have also been linked with the loss of smell alone. Just last year, NIEHS Agricultural Health Study data suggested that farmers who experienced a high pesticide exposure event were more likely lose their sense of smell decades later.

Inhalation route understudied

“Inhalation is a more translationally relevant route of exposure for paraquat than [is] injection, and critical to assess,” stressed Anderson. “Inhalation of nonvolatile pesticides is understudied because people think the likelihood of inhaling them is low. However, pesticides can become airborne when sprayed, creating the opportunity for inhalation.”

Cory-Slechta agreed. “From a broader perspective, we need to recognize that numerous studies have documented the presence of various pesticides in ambient air, and it is important to consider what health consequences might arise from those exposures,” she said.

Further study to clarify Parkinson’s link

Anderson wants to learn how paraquat alters specific brain regions. “I’m most interested in looking at the basal ganglia and the striatum,” he said. “The defining pathological feature of Parkinson’s disease is the loss of certain neurons in a network that involves those two regions.”

In addition to comparing numbers of neurons in those brain regions in exposed and non-exposed mice, the researchers want to analyze motor function. Impaired movement is another hallmark of Parkinson’s disease.

Citations:

Anderson T, Merrill AK, Eckard ML, Marvin E, Conrad K, Welle K, Oberdorster G, Sobolewski M, Cory-Slechta DA. 2020. Paraquat inhalation, a translationally relevant route of exposure: disposition to the brain and male-specific olfactory impairment in mice. Tox Sci; doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfaa183 [Online 29 December 2020]. (Summary(https://factor.niehs.nih.gov/2021/2/papers/dert/#a2))

Shrestha S, Kamel F, Umbach DM, Freeman LEB, Koutros S, Alavanja M, Blair A, Sandler DP, Chen H. 2019. High pesticide exposure events and olfactory impairment among U.S. farmers. Environ Health Perspect 127(1):17005.

(Ashley Peppriell is a Ph.D. candidate in toxicology at the University of Rochester.)