Ewan Birney, Ph.D., delivered a talk July 21 titled “Using Genetics to Understand the Environment: A Story of Fish and Humans” as part of the NIEHS Distinguished Lecture Series. He is deputy director general of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) and director of the EMBL European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI). NIEHS Health Scientist Administrator Kimberly McAllister, Ph.D., hosted the virtual event.

Birney said the study of social-genetic effects also has involved chickens, pigs, and mice. (Photo courtesy of Carrie Tang)

Birney said the study of social-genetic effects also has involved chickens, pigs, and mice. (Photo courtesy of Carrie Tang)Birney received an NIEHS grant in 2019 to study how environmental chemicals affect Japanese rice fish, also known as medaka fish. Since that project is still in its infancy, he talked instead about another one of his studies in a field called social-genetic effects, which examines the ways genetic variation can change how animals behave when they are around others.

Tried and true model

Scientists first used medaka fish as a model for studying genetics more than 100 years ago, according to Birney. Like other model organisms used in research, such as the fruit fly and plant Arabidopsis thaliana, medaka fish from the wild can be inbred and made homozygous, meaning they have two copies of the same variations, or alleles, of a particular gene.

Collaborating with scientists such as Kiyoshi Naruse, Ph.D., at the National Institute for Basic Biology in Okazaki, Japan, and Jochen Wittbrodt, Ph.D., and Felix Loosli, Ph.D., at Heidelberg University in Germany, Birney was the first to establish an inbred line of medaka fish. He and his colleagues currently have 80 medaka fish lines, each with its own genetic signature. Only female fish are used in experiments (see second sidebar).

Scared and antisocial

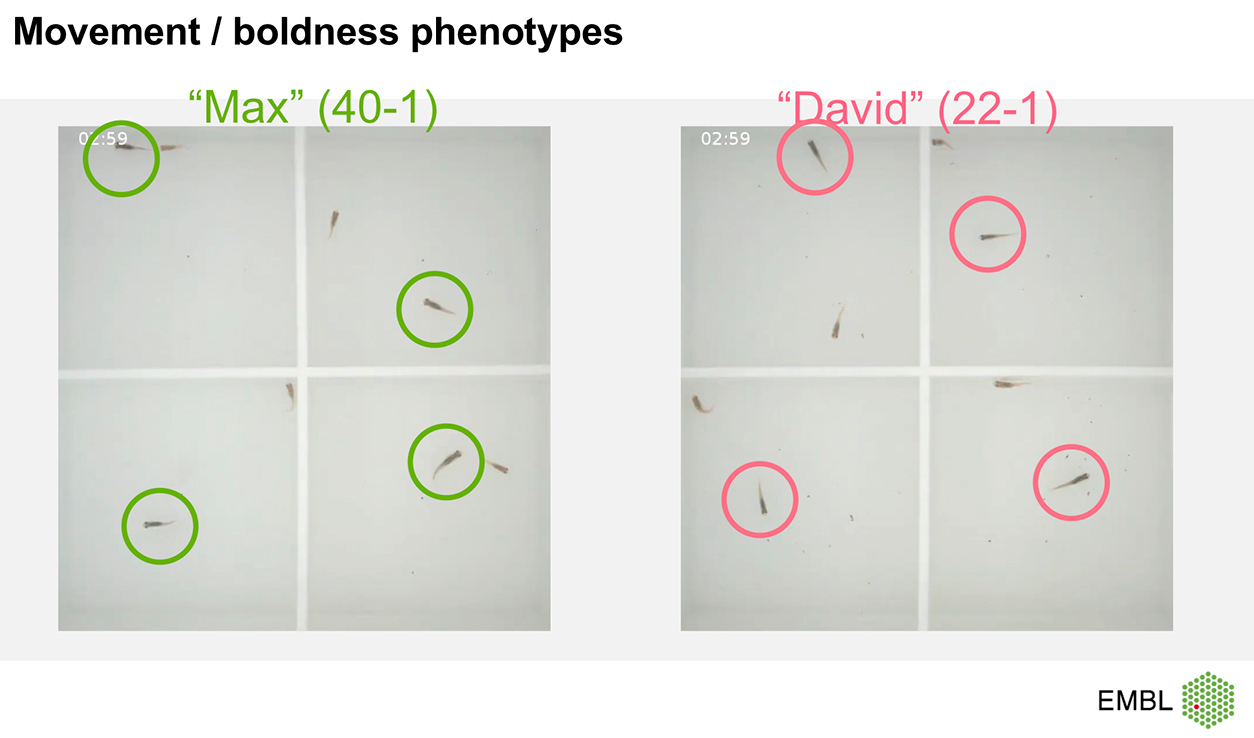

Medaka fish lines were tested using eight tanks. Four contained a female from a medaka line called Max, paired with a fish from a reference line called iCab. All fish in that reference line are genetically the same. The other four tanks contained a female from a medaka line called David and a fish from the iCab line. Water in each four-tank setup was separated by a partition, so pairs of fish could not see other pairs. A computer tracked each fish’s movements.

The research team observed that Max and iCab fish actively explored their tanks, but David fish were perfectly still.

This image shows actively moving Max fish circled in green, left, compared with the still David fish circled in red, right. The other fish are iCab. (Photo courtesy of Ewan Birney)

This image shows actively moving Max fish circled in green, left, compared with the still David fish circled in red, right. The other fish are iCab. (Photo courtesy of Ewan Birney)'The David fish are alive and will mate, but in this setting, they are petrified and are still,' Birney said. 'David and Max set up an environment for the other [iCab] fish, but it isn’t a physical or chemical environment — it is a social one.'

Mesmerizing medaka

This socialization could be seen when Birney compared David fish to another medaka line named Elsa. Female fish from that line also stayed frozen, but surprisingly, they convinced their iCab partners to follow their lead and remain relatively still.

According to Birney, David and Elsa fish set up their own social environments, with Elsa being charismatic and David less so. Birney’s team is looking forward to crossing these extremes — for example, a boring line with a charismatic line — to genetically map and understand how these social environments are created.

'Birney’s work with medaka fish illustrates the advantages of this system for studying social environmental factors and how this resource could be used for other environmental health research as well,' McAllister said.