Experts from the environmental science and health communities met Jan. 27-28 in Washington, D.C., to discuss microplastics, the tiny pieces of plastic now being detected throughout the environment. The workshop was organized by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) and sponsored by NIEHS.

“The goal was to bring together diverse viewpoints and stakeholders to talk about this complex and evolving issue,” said Nigel Walker, Ph.D., deputy division director for research at the National Toxicology Program (NTP), who helped plan the event. “I believe we succeeded and have generated a lot of enthusiasm for developing new research approaches.”

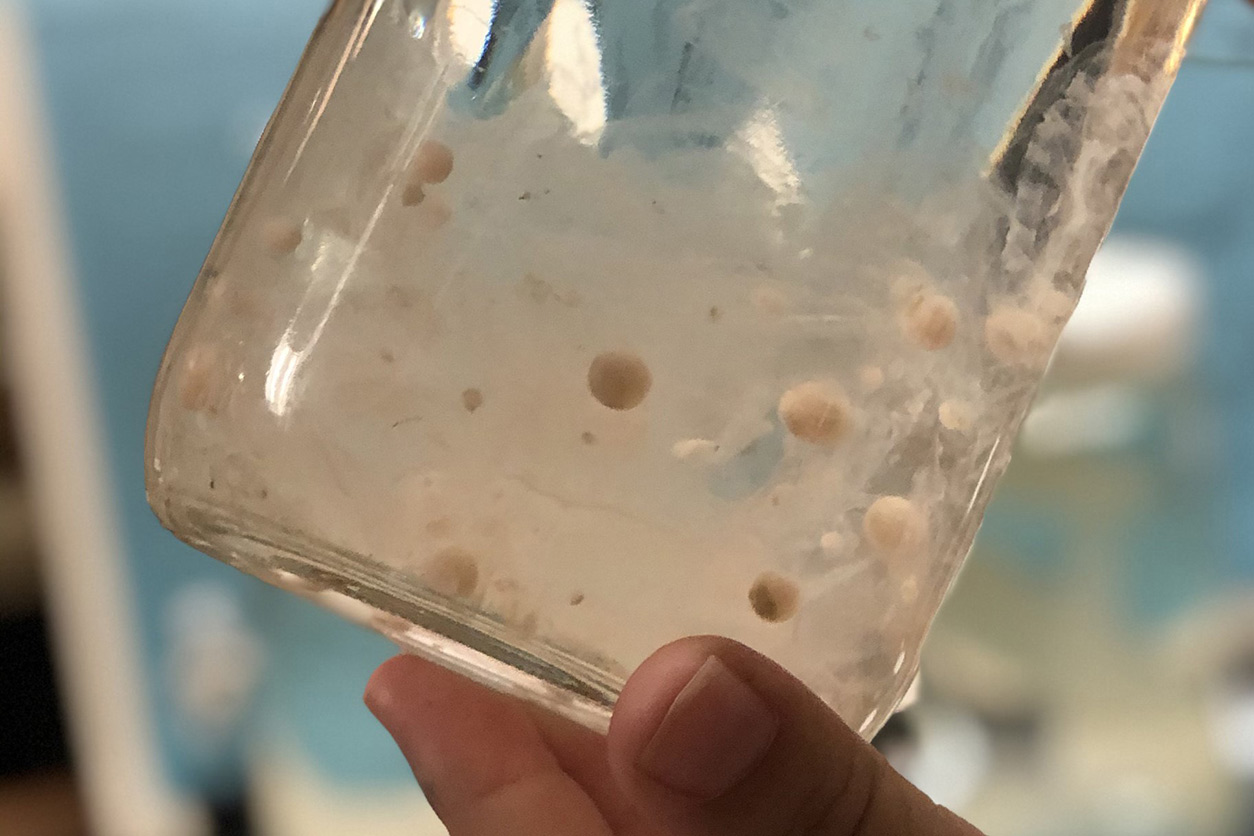

In late 2019, researchers funded by the National Science Foundation reported that microplastics were found in 100% of the tiny organisms called salps, pictured here, that they tested — a far greater abundance than previously thought. (Photo courtesy of National Science Foundation)

In late 2019, researchers funded by the National Science Foundation reported that microplastics were found in 100% of the tiny organisms called salps, pictured here, that they tested — a far greater abundance than previously thought. (Photo courtesy of National Science Foundation)A plastic world

For many decades, the production of plastics has outpaced that of any other bulk material, including steel, cement, and aluminum. In her keynote address, Kara Lavender Law, Ph.D., a research professor of oceanography at the Sea Education Association, estimated that amount as 8.3 billion metric tons to date.

“That number is so huge that I can’t give it to you in Empire State buildings, or blue whales, or Super Bowl stadiums,” she said. “It is really hard to wrap your brain around.”

Law explained that 70% of these plastics quickly become waste, breaking down into smaller and smaller bits of colorful, irregularly shaped debris. These particles scatter throughout the environment and have been found in the air we breathe, the food we eat, and the water we drink.

Walker agreed with Law, saying more research is needed before the field can move into such areas as animal studies of microplastics toxicity. (Photo courtesy of NASEM)

Walker agreed with Law, saying more research is needed before the field can move into such areas as animal studies of microplastics toxicity. (Photo courtesy of NASEM)Unknown health impact

Organisms as small as plankton and as large as humans take in those bits. Law said that many of the foods and beverages we consume are contaminated with microplastics, including honey, seafood, salt, sugar, tea, beer, bottled water, and tap water. These widespread exposures may be well documented, but their effects on human health and the health of the environment are less clear.

“The path to solutions should be informed by the best available science,” Law told the audience. “That is why we are here today: to see where we are in our understanding and how we can move forward to answer questions about the impact of microplastics.”

Several speakers noted that human health may be affected by particles small enough to be inhaled, which range from less than 3-4 microns down to nanoparticles. Microplastics at that scale have not been well characterized in terms of exposure routes, toxicological studies, and chemical makeup.

Multiple angles

Workshop participants highlighted knowledge gaps about microplastics along with possible solutions, in four main areas.

- Detecting and quantifying microplastics in food and the environment.

- Studying the effects of microplastics on the health of humans and wildlife.

- Designing ways to reduce microplastics in the environment.

- Leveraging science to inform public health and policy questions.

Jennifer Lynch, Ph.D., a research biologist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and Hawaii Pacific University, described several tools the research community can use.

In particular, she highlighted Open Specy, a spectral analysis tool specifically developed for microplastics research. The open source tool is available free online, and it allows researchers to upload and analyze their data, then share it with other researchers.

Lynch said comparing her data from Hawaii to that from other places in the world is complicated because every published study uses a different unit of measure. (Photo courtesy of NASEM)

Lynch said comparing her data from Hawaii to that from other places in the world is complicated because every published study uses a different unit of measure. (Photo courtesy of NASEM)Searching for solutions

Many of the speakers stressed the need for a standard definition of microplastics, as well as a standardized method for studying them. For example, Law suggested that automating the process of picking out plastics and identifying them, rather than relying on the human eye, could bring more objectivity to studies.

“Studying microplastics is hard because [they are] not a single contaminant like lead or a uniform contaminant like PCBs [polychlorinated biphenyls],” said NIEHS grantee Mark Hahn, Ph.D., a senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “It is a diverse and complex mixture of materials.”

“We need to have a federal strategy for funding research on this topic,” Hahn said. (Photo courtesy of NASEM)

“We need to have a federal strategy for funding research on this topic,” Hahn said. (Photo courtesy of NASEM)Workshop organizers defined microplastics as any pieces of plastic smaller than five millimeters, which is about the width of a pencil. Over time, these pieces can fragment, changing in color, shape, and size as they are exposed to oxygen, friction, and ultraviolet radiation from the sun.

Videos of presentations and slide decks are available on the workshop website.

Citation: Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL. 2017. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv 3(7):e1700782.

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)