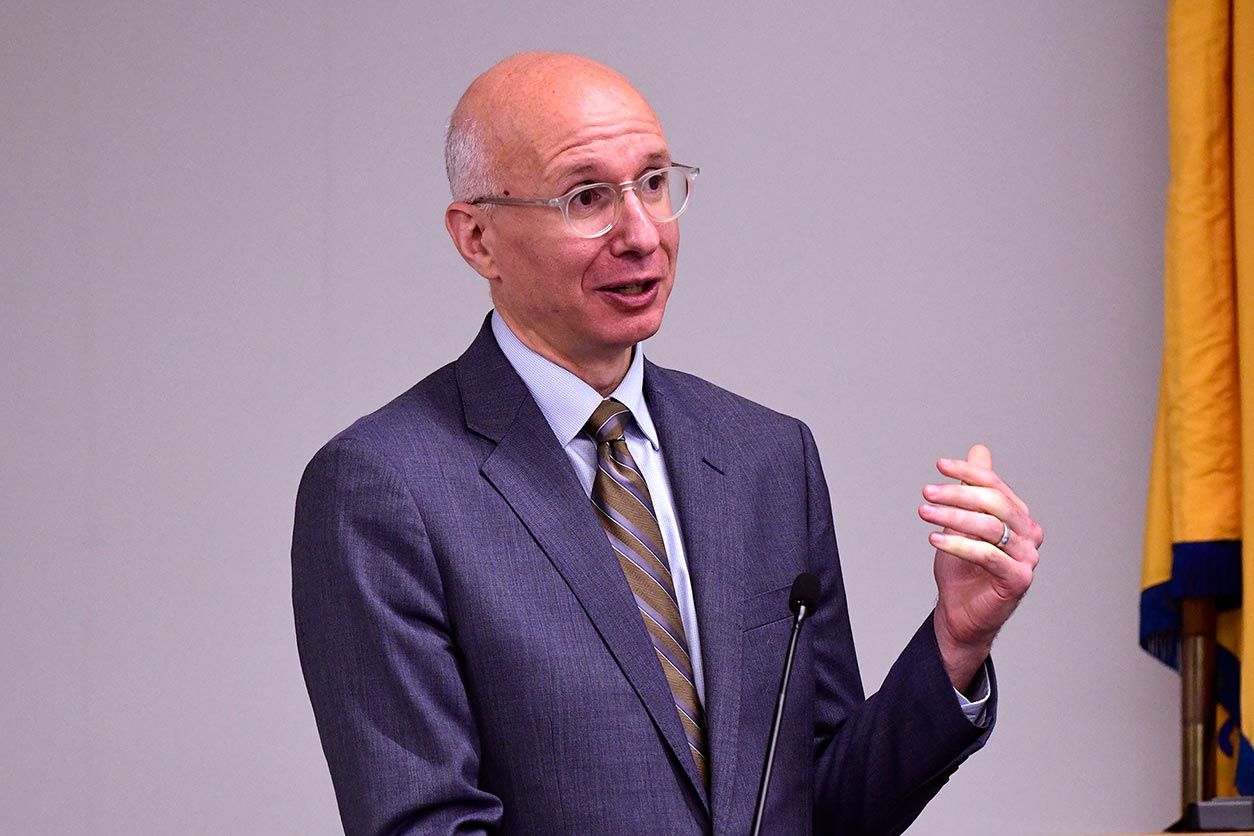

In a wide-ranging talk May 6 in Rodbell Auditorium and online, Aaron Bernstein, M.D., spoke on topics from plastics to power outages to the economics of environmental health research. But the overarching purpose of his visit was to pursue the promise of better health care outcomes through collaboration.

“I came to CDC to try to forge ways to work together across disciplines,” Bernstein said.

Bernstein directs the National Center for Environmental Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (NCEH/ATSDR) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

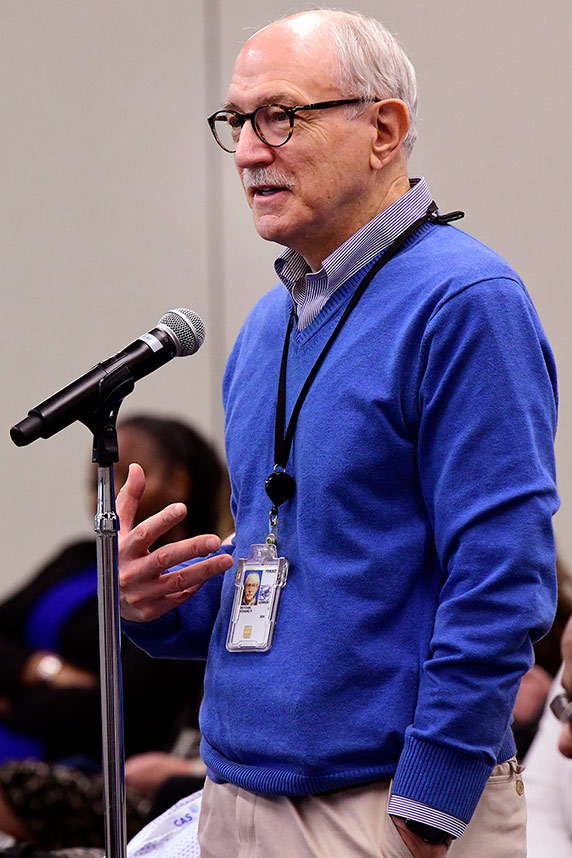

“Is better collaboration an ATSDR responsibility, an NIH or NIEHS responsibility?” asked NIEHS Director and lecture host Rick Woychik, Ph.D. “Who can Congress and the American public point to for supporting this phenomenal research infrastructure and generating answers?”

“We’ve got to figure this out together,” said Bernstein. “We need to work with NIEHS, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Environmental Protection Agency, to address the most pressing public health issues, particularly for communities that have been left behind.”

Unasked questions

Public health emergencies, said Bernstein, can reveal how better institutional cooperation might help us see research blind spots. For example, he said that when research questions fall through the cracks unasked, agencies may be underprepared to respond effectively. He pointed to the following recent events that he said disproportionately affected environmental justice communities.

- Last year, seawater intrusion up the Mississippi River led to questions about how much salinity, or salt in drinking water, was safe for children. “We knew salinization happened, but we hadn't asked that question,” he said.

- Following the 2023 wildfires in Canada and Hawaii, researchers realized they had no data about whether masks protect from wildfire smoke in community populations. “It makes a lot of sense that N95s are probably effective at filtering out particulates,” he said. “But the scientific answers were unknown.”

The wildfire in Lahaina incinerated and aerosolized many sources of toxins, from lead acid batteries to foam insulation. “Wildfire smoke may be more toxic than traditional fossil fuel particulates,” Bernstein said. “Questions like how hot a fire is, and whether that affects toxicants, need investigation.” He noted that post-wildfire soil tests found less dangerous compounds were present than was expected.

- The linear scale of the EPA’s Air Quality Index (AQI) shows increased risk at higher doses of air pollution, but recent studies suggest exposure at lower levels may be just as harmful. “This is a huge public health question, especially now that the AQI is on everyone's phones,” Bernstein said.

- Weather-related power outages have risen dramatically since 2000, Bernstein said. Dependence on electric medical devices, especially those that run on batteries (oxygen concentrators, wheelchairs, etc.) has become a major public health challenge.

“This is an opportunity for collaboration, because there is real data collected around power outages, particularly from utilities,” he said.

Microplastics

Plastics represent a burgeoning disease burden, Bernstein said, and research into how they get into our bodies and how they impact our health will be enhanced by collaboration.

He cited a study in the New England Journal of Medicine showing the incidence of cardiovascular events is higher in people with high burdens of micro- and nanoplastics. Interestingly, the authors didn't study the chemistry, but rather the morphology — how the shape and size of these small plastic particles cause damage through abrasion.

“This is not a toxic event, per se,” Bernstein said. “But, when particles get into blood vessels, things get sticky and form clots to defend themselves.”

The environment’s place in health care

During his talk, Bernstein also noted that environmental health is often not top of mind in the U.S. health care system.

“People get sick, then we spend a lot of money trying to make them less sick,” Bernstein said. “But all of us here are charged primarily with trying to keep people from getting sick in the first place.”

Woychik lauded Bernstein’s eagerness to collaborate, and said he was excited about NIEHS working more closely with the CDC.

“As an environmental health scientist and pediatrician, Dr. Bernstein brings a lot to the table,” Woychik said. “I’m looking forward to working with him to bridge research gaps that will ultimately improve health.”

(John Yewell is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)