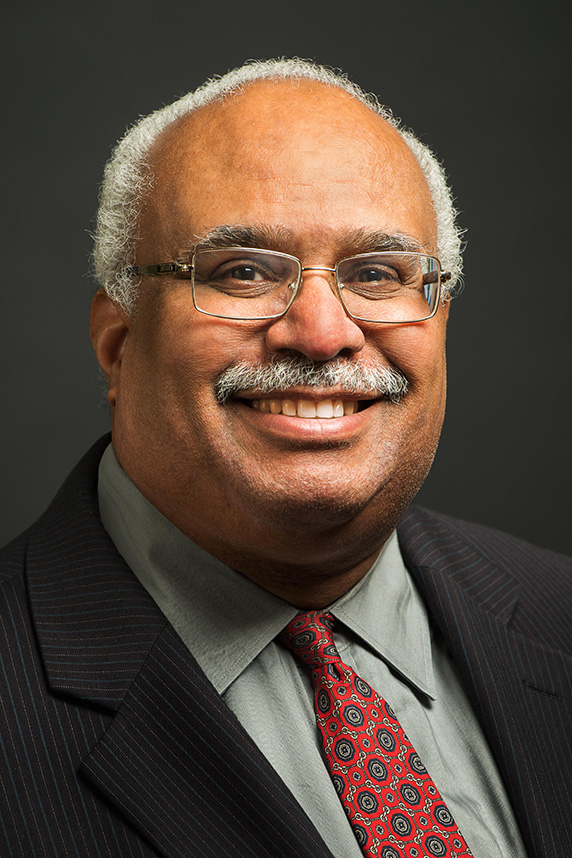

“Underserved communities tend to be disproportionately impacted by climate change,” said Benjamin. (Photo courtesy of Georges Benjamin)

“Underserved communities tend to be disproportionately impacted by climate change,” said Benjamin. (Photo courtesy of Georges Benjamin)How climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic have increased health risks for low-income individuals, minorities, and other underserved populations was the focus of a Sept. 29 virtual event. The NIEHS Global Environmental Health (GEH) program hosted the meeting as part of its seminar series on climate, environment, and health.

“People in vulnerable communities with climate-sensitive conditions, like lung and heart disease, are likely to get sicker should they get infected with COVID-19,” noted Georges Benjamin, M.D., executive director of the American Public Health Association.

Benjamin moderated a panel discussion featuring experts in public health and climate change. NIEHS Senior Advisor for Public Health John Balbus, M.D., and GEH Program Manager Trisha Castranio organized the event.

Working with communities

“When you couple climate change-induced extreme heat with the COVID-19 pandemic, health threats are multiplied in high-risk communities,” said Patricia Solis, Ph.D., executive director of the Knowledge Exchange for Resilience at Arizona State University. “That is especially true when people have to shelter in places that cannot be kept cool.”

“There's two ways to go with disasters. We can return to some kind of normal or we can dig deep and try to transform through it,” Solis said. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Solis)

“There's two ways to go with disasters. We can return to some kind of normal or we can dig deep and try to transform through it,” Solis said. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Solis)She said that historically in Maricopa County, Arizona, 16% of people who have died from indoor heat-related issues have no air conditioning (AC). And many individuals with AC have malfunctioning equipment or no electricity, according to county public health department records over the last decade.

“We know of two counties, Yuma and Santa Cruz, both with high numbers of heat-related deaths and high numbers of COVID-19-related deaths,” she said. “The shock of this pandemic has revealed how vulnerable some communities are. Multiply that by what is already going on with climate change.”

Solis said that her group has worked with faith-based organizations, local health departments, and other stakeholders to help disadvantaged communities respond to climate- and COVID-19-related issues, such as lack of personal protective equipment.

“Established relationships are a resilience dividend we can activate during emergencies,” she said. “A disaster is not the time to build new relationships.”

Personalizing a disaster

“We have to make sure everybody has resources to prepare for and recover from a disaster,” Rios said. (Photo courtesy of Janelle Rios)

“We have to make sure everybody has resources to prepare for and recover from a disaster,” Rios said. (Photo courtesy of Janelle Rios)Janelle Rios, Ph.D., director of the Prevention, Preparedness, and Response Consortium at the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Public Health, recounted her experience during Hurricane Harvey in Houston in 2017. Rios and her husband had just bought a new home there and were in the process of moving.

“We had flood insurance and a second house, but friends with fewer resources were traumatized,” Rios said. A lab tech friend lost her home and lived for months with her husband and dog in Rios’s garage apartment. A member of the health center cleaning staff had to be rescued by boat and ended up in a crowded shelter. Rios discussed those experiences in the context of concepts such as equality and equity.

“Imagine moving large numbers of people into shelters during a pandemic,” Benjamin said. “Some 40% of people with COVID-19 have no symptoms.”

According to Rios, local public health officials and decision-makers would benefit from learning more about the science behind climate change and related health effects, including those involving mental health.

Climate change adaptation and mitigation

Nicole Hernandez Hammer recently became a staff scientist at UPROSE, a Latino community-based organization in the Sunset Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York.

“My position is unique because a lot of community organizations don't have an on-staff scientist,” said Hernandez Hammer. “We're developing a new model.” (Photo courtesy of Nicole Hernandez Hammer)

“My position is unique because a lot of community organizations don't have an on-staff scientist,” said Hernandez Hammer. “We're developing a new model.” (Photo courtesy of Nicole Hernandez Hammer)She said that many Sunset Park residents cope with climate-sensitive underlying health conditions. According to Hernandez Hammer, those individuals understand the need to address climate change to lessen their vulnerability to COVID-19.

“Immigrant communities know about resilience and adaptation,” she said. “We are in a position to lead on climate change adaptation and mitigation.”

Before joining UPROSE, Hernandez Hammer studied climate-related tidal flooding in frontline, low-lying Miami neighborhoods. High levels of Escherichia coli have been found in the water there.

“Sunny-day flooding happens about a dozen times a year in south Florida,” she said. “According to Army Corps of Engineers sea level rise projections, by 2045, in many places in the U.S., it may happen as many as 350 times a year.”

Scientists should work harder to collaborate and share research with communities facing climate- and COVID-19-related health problems, according to Hernandez Hammer.

(John Yewell is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)