'We need to change the conversation and start talking about health disparities in a way that involves income inequality,' Olden said. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

'We need to change the conversation and start talking about health disparities in a way that involves income inequality,' Olden said. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Kenneth Olden, Ph.D., served 14 years as NIEHS and National Toxicology Program director (1991-2005) and three as senior investigator and head of the Metastasis Group. When he left in 2008, he knew he would come back to visit, but did not expect it would be as the honoree of a named lecture.

The Olden Distinguished Lecture: Promoting Diversity, Inclusion, and Scientific Excellence was webcast Sept. 21(https://www.niehs.nih.gov/news/video/diversity/#900897). Olden’s lecture, titled 'Economic Inequality and Health,' spoke to the reasoning behind establishing the series.

'The series will showcase outstanding scientists from underrepresented groups doing innovative research in environmental health, environmental justice, and environmental health disparities,' said NIEHS and National Toxicology Program Director Rick Woychik, Ph.D. 'These are topics Dr. Olden is passionate about and has championed throughout his career, especially during his tenure at NIEHS.'

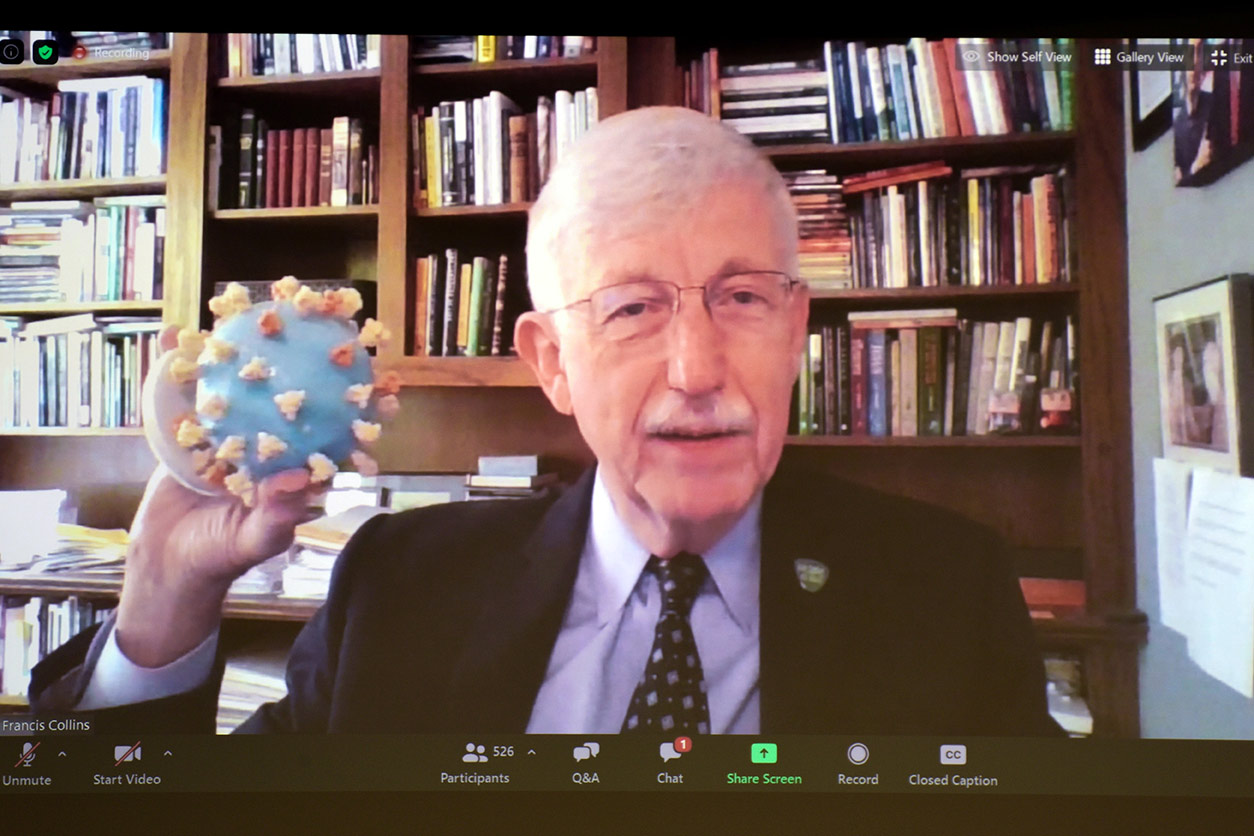

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D., also provided remarks. From his home office, Collins addressed the socially distanced attendees in Rodbell Auditorium and more than 100 watching online.

'Congratulations to NIEHS for initiating this distinguished lecture,' Collins said. 'It is a wonderful way to recognize Ken’s enduring legacy of excellent science and to focus on the ways excellent science is connected to diversity.'

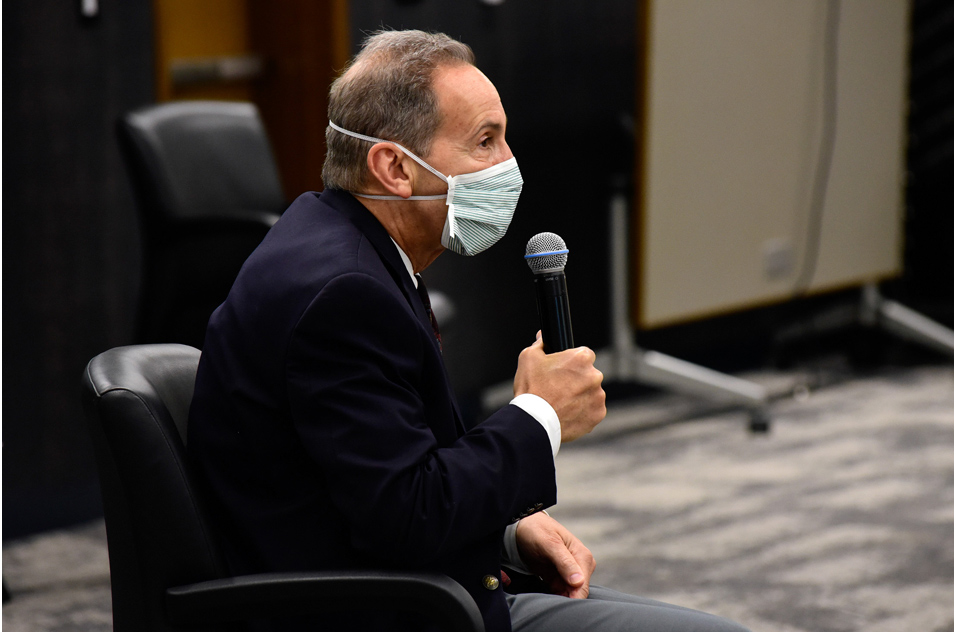

During his remarks, Collins held up a model of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

During his remarks, Collins held up a model of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)A tale of two cities

Olden said public health researchers have produced a substantial body of literature documenting the link between income and life expectancy in the U.S. He said during the past century, life expectancy for men increased from 48 years to 74 years, and for women from 52 years to 80 years.

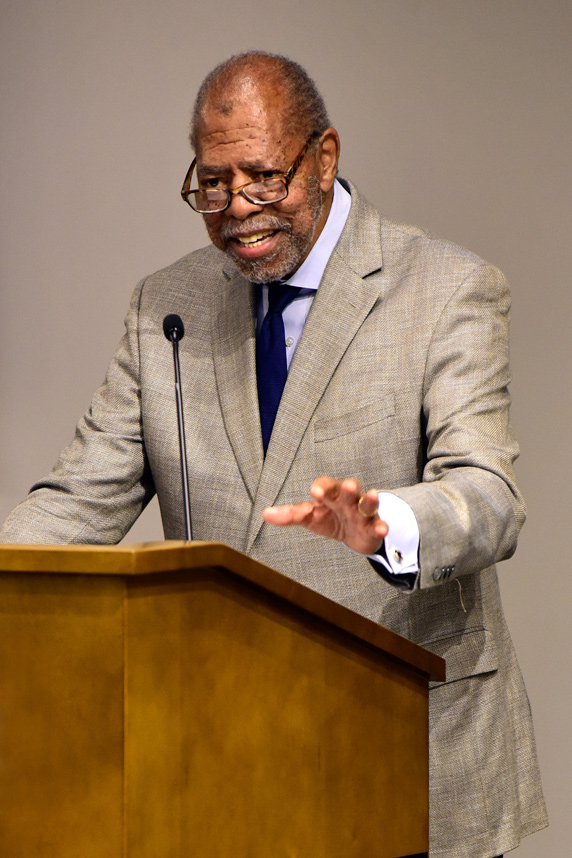

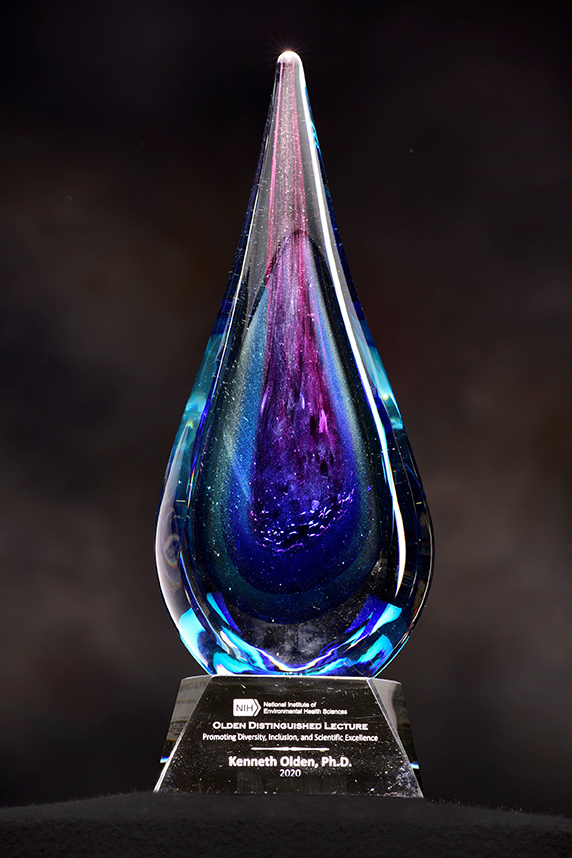

Olden received this beautiful award, and every future presenter of his namesake lecture will receive one, too. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Olden received this beautiful award, and every future presenter of his namesake lecture will receive one, too. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Olden stressed that these remarkable gains have not benefitted all Americans and offered data from two neighborhoods in the Los Angeles area, by way of example. A young man living in zip code 90002, which is Watts, has a life expectancy of 72 years, but if he was born in 92606, which is Irvine, he could expect to live 86 years.

This difference of 14 years is not the only discrepancy. The average income for people living in Watts is $31,000, while those in Irvine make an average of $108,000. Seventy-two percent of the Watts population are people of color. Irvine is 48% white and 42% Asian.

The distance between the two communities is about 37 miles, so Olden and his colleagues wondered if they compared neighborhoods that were geographically closer within a large metropolitan area if they would find the same disparities. His team examined neighborhoods in New Orleans and New York City and saw the same gaps.

'The data we gathered indicated that Blacks and low-income earners live in the neighborhoods that are disparaged,' Olden said. 'The data also suggests that health disparities are caused by a combination of all of the social determinants.'

Healthy People 2020, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, describes social determinants of health as including economic stability, education, social and community context, health and healthcare, neighborhood and the built environment, and more. Olden’s data suggested economic inequality is the driver of all the social determinants of health.

Income and life expectancy

After reviewing data from the past 40 years, Olden found the richest men live 15 years longer than the poorest men. For women, the difference is 10 years. He said $2.5 trillion is coming out of workers’ pockets and going to shareholders in our capitalistic society. Unless we change our economic disparities, health disparities will continue to grow.

Olden closed by stressing that although most Americans view health disparities as an issue that only impacts poor, racial, and ethnic minorities, we are all in the same boat. Our income bracket determines how much our life expectancy decreases.

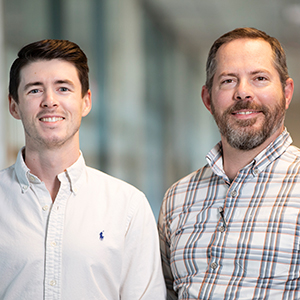

Like others attending the lecture in person, Woychik, right, and Archer, left, were tested for the novel coronavirus twice, wore masks, and were seated at least six feet apart. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Like others attending the lecture in person, Woychik, right, and Archer, left, were tested for the novel coronavirus twice, wore masks, and were seated at least six feet apart. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Trevor Archer, Ph.D., chief of the Epigenetics and Stem Cell Laboratory and an NIH Distinguished Investigator, moderated the question and answer session. Archer proposed that NIEHS establish the Olden Distinguished Lecture as part of its ongoing commitment to diversify the scientific workforce and use research to address racial health disparities. His idea brings NIEHS closer to its inclusion goals.