NIEHS grantees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a new toxicity test that can directly and accurately measure the impact of chemicals on cell survival in a matter of days. The discovery, reported in the journal Cell Reports, could allow academic researchers and drug companies to more rapidly evaluate environmental contaminants and new drugs for possible harmful effects.

“This new method solves a major problem in toxicity testing today,” said Daniel Shaughnessy, Ph.D., program officer in the NIEHS Exposure, Response, and Technology Branch. “It takes a difficult and time-consuming process and makes it easier, faster, and more efficient.”

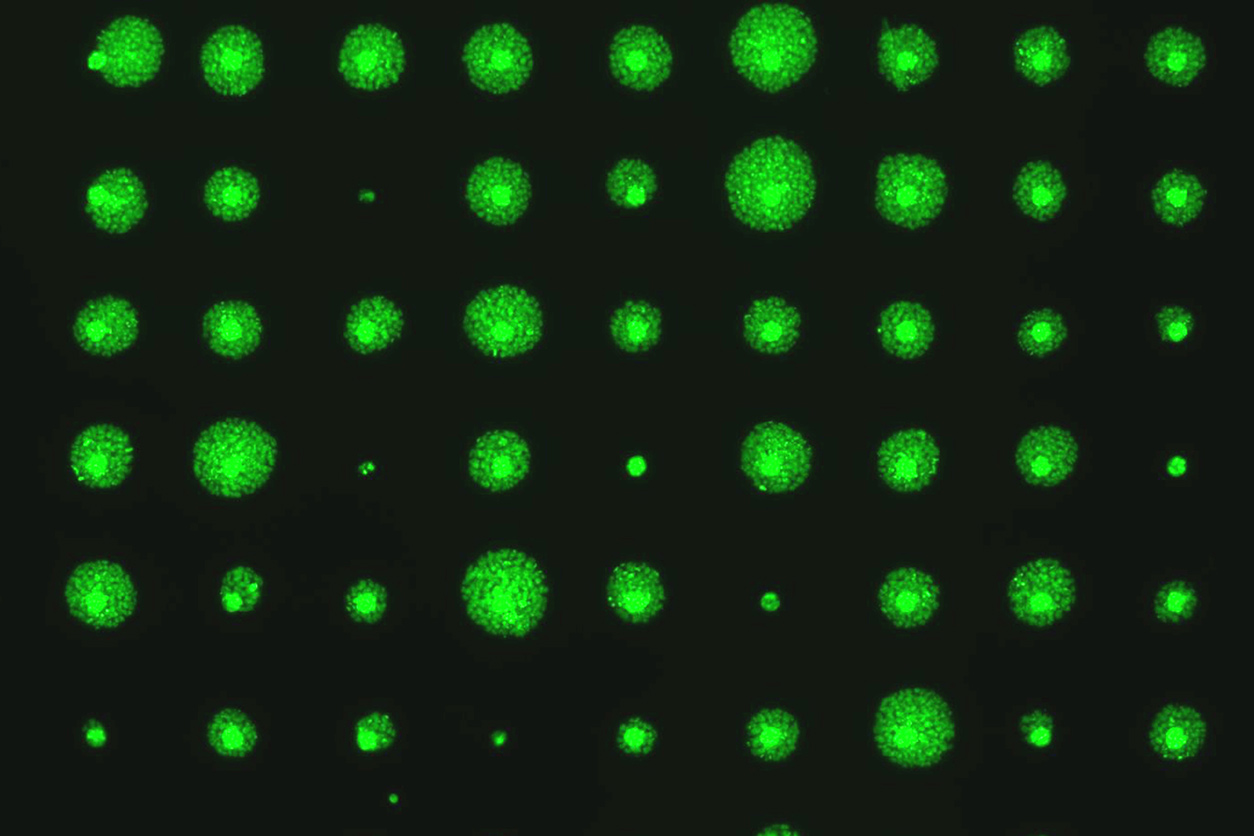

NIEHS grantees at MIT have developed a way to rapidly measure cell survival rates by growing microscopic cell colonies and imaging their fluorescently labeled DNA. (Photo courtesy of Le Ngo)

NIEHS grantees at MIT have developed a way to rapidly measure cell survival rates by growing microscopic cell colonies and imaging their fluorescently labeled DNA. (Photo courtesy of Le Ngo)A time sink

Cell survival, compared with cell death, is a common measure used in biology. Cell survival tests can tell scientists a lot about the health of cells, and, in turn, their environment. Cells that survive when they should not could point to the origins of cancer. Cells that die after exposure to drugs or chemicals could reveal toxic side effects.

For decades, the gold standard for measuring cell survival has been a test called the colony formation assay. This technique, according to a MIT press release written by Ann Trafton, grows cell colonies on Petri dishes for two to three weeks after exposing the cells to a chemical compound or potentially harmful agent, such as radiation. A researcher then counts the number of colonies by eye to determine how the treatment affected the cells’ survival.

Senior study author Engelward is program director of the MIT Superfund Research Program Center. (Photo courtesy of MIT)

Senior study author Engelward is program director of the MIT Superfund Research Program Center. (Photo courtesy of MIT)“Few people use the colony formation assay anymore because it’s difficult, way too slow, and requires huge amounts of cell growth media, so you need a lot of the compound being tested,” said Bevin Engelward, Sc.D., in the press release. Engelward is a professor of biological engineering at MIT and co-senior author with Leona Samson, Ph.D., also from MIT.

So scientists turned to alternative methods that promised faster results. Instead of measuring cell growth directly, these tests rely on other measures that indicate cell survival, such as the rate of cellular metabolism or levels of a molecule called ATP, also known as adenosine triphosphate, which cells use for energy. As a result, the alternative tests are not as accurate as the cell counting technique.

Size matters

In their study, Engelward and her team set out to develop a test as accurate as the traditional assay and as quick as newer methods. The result is a tiny, automated system called the MicroColonyChip.

First, the scientists deposited cells onto a microwell array with thousands of miniature wells on a single rectangular plate. After a few days, they attached fluorescent labels to DNA in the treated and untreated cells that they wanted to study. Then, they placed the plates under a microscope and took pictures of the colonies that emerged. Using a computer algorithm that accounted for the average amount of fluorescence per cell, differences in the distribution of colony sizes were calculated to reveal the extent of cell growth.

Best of both worlds

When the researchers compared results of the MicroColonyChip with both the traditional colony formation assay and newer, indirect tests, they found their invention performed as well, and in some cases better, than current approaches. For example, when measuring cell survival after exposure to radiation, the MicroColonyChip was several times more sensitive than a popular cytotoxicity test called the XTT assay.

“The new test provides the best of both worlds — results that are accurate and sensitive, and in a couple of days, instead of weeks,” said Shaughnessy. “It is an exciting advance.”

The researchers say the test could be used for a wide variety of applications, such as drug development, environmental regulation, and personalized medicine. They have filed for a patent on their new technology.

Citation: Ngo LP, Chan TK, Ge J, Samson LD, Engelward BP. 2019. Microcolony size distribution assay enables high-throughput cell survival quantitation. Cell Reports 26(6):1668−1678.

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)