Toxicologists, policy analysts, industry and community representatives, and North Carolina state legislators met Oct. 23-24 in Durham, for a summit on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Those man-made chemicals exist in many products, such as nonstick cookware and firefighting foam.

Research shows possible links between some PFAS and a variety of negative health outcomes, such as increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of thyroid disease, and reduced fetal growth. The conference, co-sponsored by the Research Triangle Environmental Health Collaborative and the North Carolina PFAS Testing Network, focused on how scientists and policymakers can work together to reduce potential harm from the substances.

In recent years, high levels of PFAS have been discovered in some drinking water systems in North Carolina.

In recent years, high levels of PFAS have been discovered in some drinking water systems in North Carolina.Collaboration and debate

The meeting highlighted work from the testing network, a research partnership that includes NIEHS grantees. It was formed after the Cape Fear River, the water source for Wilmington, was found contaminated with a type of PFAS called GenX in 2017. State lawmakers provided funding for university scientists to measure the chemicals’ concentrations in water and air samples across North Carolina, analyze potential health effects, and develop treatment solutions.

“For me, as a scientist, it’s been very interesting and rewarding to grow and develop relationships with people from impacted communities,” said grantee Jamie DeWitt, Ph.D., of East Carolina University (ECU), who is supported by the network. Among other projects, her team at ECU looks at understudied PFAS to better grasp their effects on the immune system.

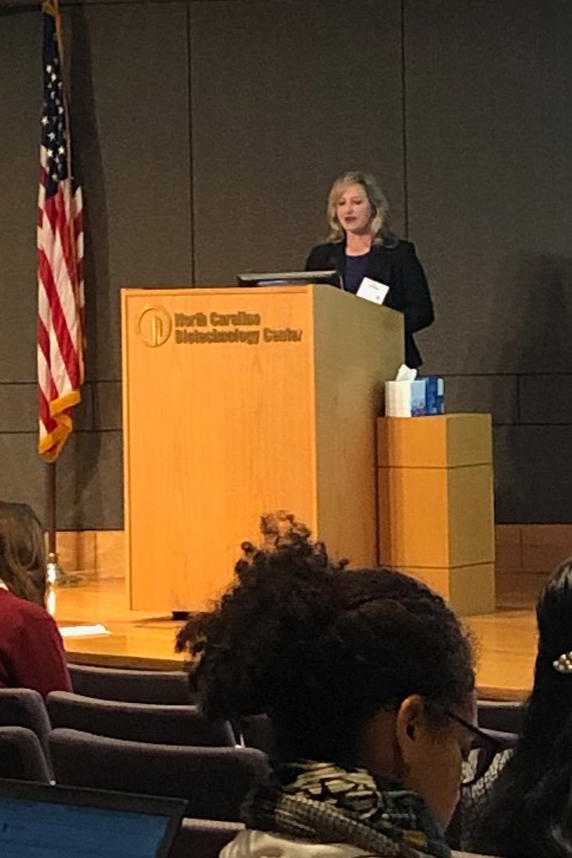

Fenton is head of the National Toxicology Program’s Reproductive Endocrinology Group. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Fenton is head of the National Toxicology Program’s Reproductive Endocrinology Group. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)DeWitt participated in a working group at the conference that included National Toxicology Program scientist Sue Fenton, Ph.D. Fenton presented research comparing different PFAS’ effects on pregnant mice. Attendees explored many other topics, such as the following.

- Patrick Breysse, Ph.D., director of the National Center for Environmental Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, highlighted federal efforts to monitor PFAS exposure across the country.

- A working group that included grantee Scott Belcher, Ph.D., of North Carolina State University, examined ways PFAS can spread in the environment and persist for long periods.

- Five state senators and representatives discussed how the chemicals have affected different communities across the state.

- Heather Henry, Ph.D., health scientist administrator for the Superfund Research Program, spoke about new research aimed at improving remediation and cleanup (see sidebar).

- Representatives from the Chemours Company emphasized the complexity of PFAS and why they think the chemicals should not be lumped together in scientific or policy debates.

“Kind of scary”

At the end of the conference, some participants expressed desire to see more funding for PFAS research, more collaboration between government and private entities in North Carolina, and more educational outreach, especially to susceptible groups such as pregnant women.

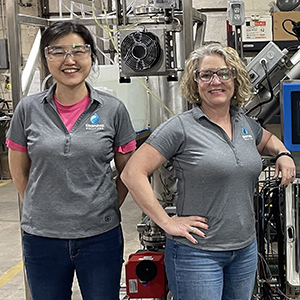

Henry noted that several grantees are developing technologies to absorb and destroy PFAS. (Photo courtesy of Jesse Saffron)

Henry noted that several grantees are developing technologies to absorb and destroy PFAS. (Photo courtesy of Jesse Saffron)“I used to tell my citizens that their water is safe to drink — we are state-tested, federal-tested, and we’re meeting all regulations. Now, I’m a little cautious of saying it’s safe,” said Schumata Brown, town manager for Maysville, North Carolina. He participated in a discussion about how communities in the Tar Heel State are addressing PFAS contamination.

Earlier this year, PFAS concentrations above the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s advisory levels were detected in Maysville and the town had to switch to a nearby municipality’s water system. The North Carolina PFAS Testing Network discovered the contamination.

“It’s kind of scary what’s out there that we don’t know about,” said North Carolina Senator Rick Gunn. “I think we’re in a good time in our state to have the right expertise [and] the financial support from not only state but private concerns. I think that moving forward, we should have positive results.”

(Jesse Saffron, J.D., is a technical writer-editor in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)

The audience listened closely as experts discussed the chemicals.