Living in green neighborhoods could reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease in susceptible individuals by decreasing the body’s stress and boosting its ability to repair blood vessels, according to new research funded by NIEHS.

The study, which was published Dec. 5 in the Journal of the American Heart Association, also suggested that greener neighborhoods might provide greater benefits for women and individuals at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease.

High levels of residential greenness are linked with decreased biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk.

High levels of residential greenness are linked with decreased biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk.Neighborhood green spaces may protect heart

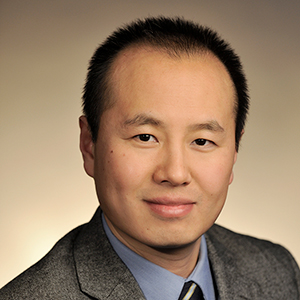

“These measurements provide the first line of direct evidence of physiological changes in people as a result of living in green spaces,” said senior author Aruni Bhatnagar, Ph.D., from the University of Louisville. “The overall significance of our findings is that they support the transformation of urban greenness from a pleasant nicety to an essential health requirement.”

Bhatnagar is interested in better understanding how oxidative stress affects cardiovascular function. (Photo courtesy of Aruni Bhatnagar)

Bhatnagar is interested in better understanding how oxidative stress affects cardiovascular function. (Photo courtesy of Aruni Bhatnagar)Extensive evidence suggests that many features of the environment can affect cardiovascular disease risk. However, the health effects of neighborhood green spaces have received relatively little attention.

Past studies that showed a link between green spaces and cardiovascular health mainly relied on subjective questionnaires rather than objective biological measurements. As a result, the body’s processes that are involved in the protective response remain unclear.

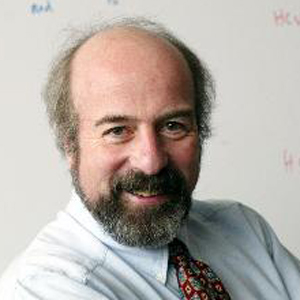

“In addition to specific findings of the effects of neighborhood green spaces for cardiovascular health, this study is an example of research that focuses on environmental factors that can prevent or protect health, rather than addressing only illness or disease,” said Symma Finn, Ph.D., a program officer in the Population Health Branch at the NIEHS. “This focus on health promotion, which is rigorously explored in Dr. Bhatnagar’s study, is an important movement in biomedical and environmental health sciences research.”

The benefits of going green

Finn has been a scientific research administrator since 1984, and has worked in academia, for a rare genetic disease organization, and at the National Institutes of Health. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Finn has been a scientific research administrator since 1984, and has worked in academia, for a rare genetic disease organization, and at the National Institutes of Health. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)To address this gap in knowledge, Bhatnagar and his collaborators measured biomarkers of cardiovascular disease in individuals who lived in neighborhoods that varied widely in greenness. The study participants included 408 outpatients from a preventive cardiology clinic.

The greenness of their neighborhoods was estimated based on satellite data related to the coverage and density of vegetation.

Greenness levels within a 250 meter and 1 kilometer radius around participants’ residences were associated with lower urinary levels of a stress-related hormone called epinephrine. This effect was stronger in several populations — women, participants who were not taking blood pressure medications called beta-blockers, and individuals who had not previously experienced a heart attack.

Higher vegetation density was also linked to lower urinary levels of a molecule called F2‐isoprostane, which serves as a biomarker of oxidative stress. This finding suggests that exposure to green spaces might be associated with a decrease in oxidative stress. Moreover, blood cell measurements revealed that living in green neighborhoods was associated with a better capacity for wound healing and repairing blood vessels.

“The findings should encourage individual exposure and interactions with nature,” Bhatnagar said. “Our results could also spur city developers and urban planners to enhance urban greenery, which not only has significant aesthetic value, but also has quantifiable health benefits.”

Citation: Yeager R, Riggs DW, DeJarnett N, Tollerud DJ, Wilson J, Conklin DJ, O'Toole TE, McCracken J, Lorkiewicz P, Xie Z, Zafar N, Krishnasamy SS, Srivastava S, Finch J, Keith RJ, DeFilippis A, Rai SN, Liu G, Bhatnagar A. 2018. Association between residential greenness and cardiovascular disease risk. J Am Heart Assoc 7(24):e009117. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009117.

(Janelle Weaver, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)