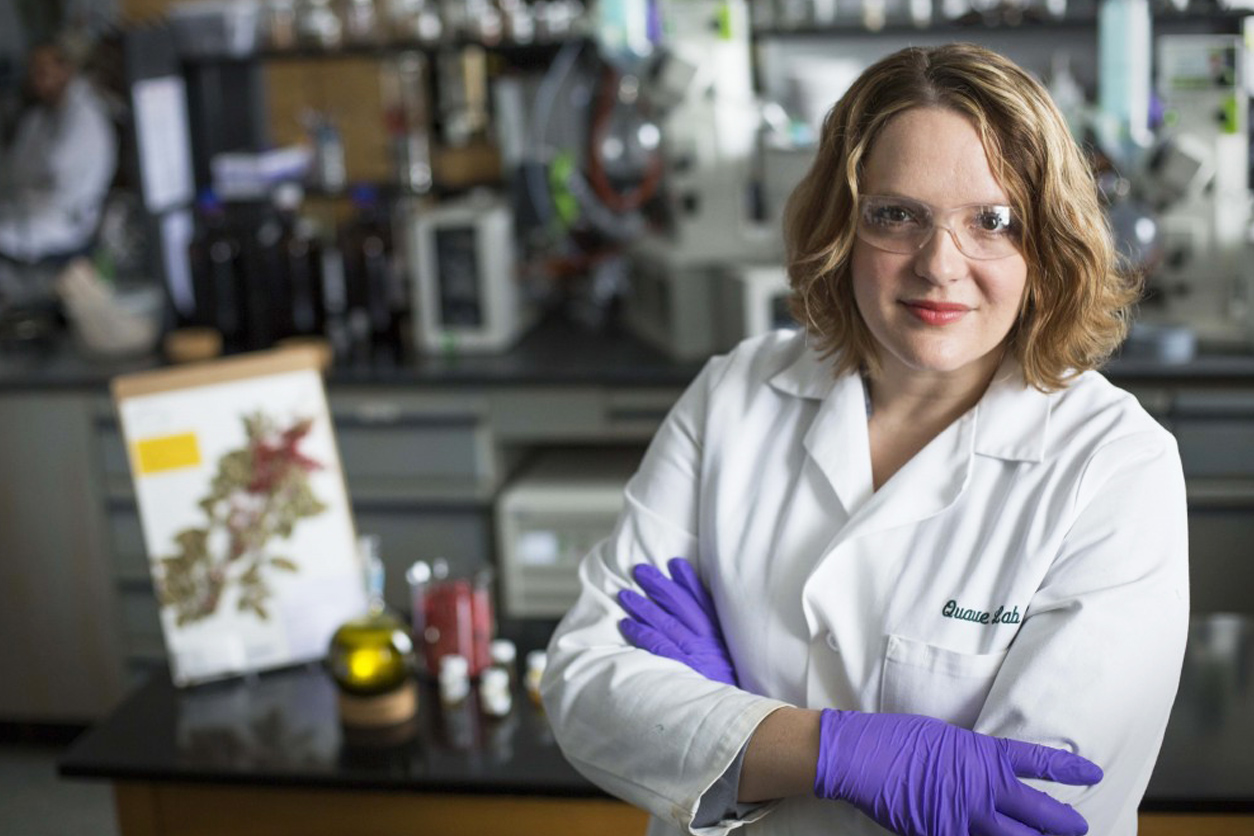

Pursuing a scientific career as both a woman and a person with a disability is not easy, says Cassandra Quave, Ph.D., but a passion for discovery is her guiding light. Quave, an Emory University associate professor and herbarium curator, spoke about her journey during the Spirit Lecture held virtually and at NIEHS March 26. The Spirit Lecture honors outstanding women in science in recognition of Women’s History Month each March.

As a medical ethnobotanist, Quave travels to remote places in search of plant extracts with human health benefits, relying heavily on the knowledge and expertise of Indigenous groups. She has published more than 100 scientific articles, two books, and 20 book chapters, and she holds seven patents.

NIEHS Postbaccalaureate Fellow Abra Granger introduced Quave at the Spirit Lecture, calling her “a steadfast mentor who fosters and encourages curiosity, and faces challenges head on, not only in research, but as a daughter, sister, and a mother.”

The annual lecture, which is part of the NIEHS Diversity Speaker Series, highlights inspiring scientists who successfully navigate finding balance among the workplace, family, and other responsibilities.

Early challenges

Born with skeletal defects that caused chronic ankle breaks and mobility challenges, Quave explained that physicians amputated part of her leg when she was 3 years old so that she would have a better chance of walking with a prosthetic leg. After developing a Staphylococcus infection, Quave was rushed back to the hospital where she underwent intensive antibiotic therapy and additional surgeries.

Spending so much time in the hospital and at home recovering was tough, Quave said, given her innate love of nature. But when her mother brought home a microscope, everything changed.

“That moment of looking through the microscope was a revelation,” recalled Quave. “While I couldn't go out and enjoy the macroworld, I could enjoy the microworld.”

Her growing curiosity led her to enter the world of science fairs, where she described herself as a fierce competitor.

“For me, science became like a sport,” said Quave. “I grew up in the 1980s when there weren't opportunities for disabled children. But I started getting into science and realized, ‘Wow, I'm really good at this.’”

Finding focus

At first, Quave attended Emory University to become a pediatric orthopedic surgeon, following in the steps of those who cared for her as a child. But a medical anthropology course opened her eyes to new perspectives. She learned that although some cultures view disability as something to be pitied or intentionally ignored, disabled people are considered special and possessing of spiritual power in other cultures.

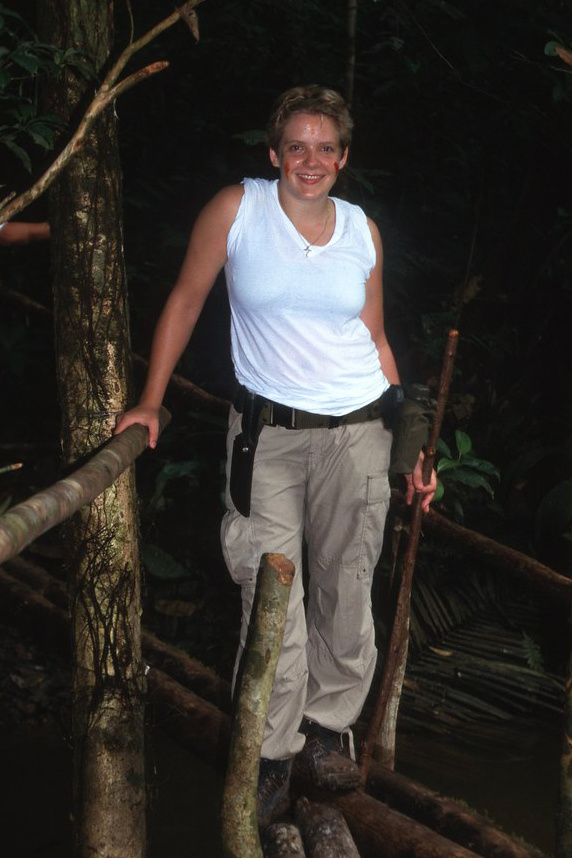

Quave began to think about herself — and medicine — in a different way. Double majoring in biology and anthropology, she traveled to the Amazon rainforest after her junior year to study medical practice in Peruvian culture. There, she met a community healer treating patients with various ailments using plants and holistic techniques.

“He taught me that medicine is about so much more than pharmacy or surgery,” said Quave. “It is about your connection with others.”

The experience led her to forego medical school and begin a research career in ethnobotany — the study of the relationship between plants and humans — instead. After college, and before starting a biology doctorate at Florida International University, she participated in a project documenting traditional names for wild foods in southern Italy. There she met her future husband, with whom she now has four children.

Although Quave admitted that remote fieldwork with a prosthetic leg and sometimes a family in tow requires creativity and sacrifice, she emphasized that it is ultimately “all about the attitude and the spirit with which you approach your work.”

Developing solutions

Quave’s research group, which receives grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, uses ethnobotany to inform drug development for a wide range of conditions, from eczema to antibiotic resistance. Her team operates a chemical library, the Quave Natural Products Library, that houses more than 2,500 extracts from more than 750 species.

For one project, Quave is developing a drug for eczema using extracts from the Brazilian pepper tree and the European chestnut tree. Quave seeks to pharmaceutically mimic the trees’ ability to turn off bacterial cells’ communication networks. In this way, the trees, and potential drug, would prevent bacteria from effectively colonizing and releasing toxins that cause significant tissue damage in people with eczema.

In another project, Quave found that an extract from the roots of the elmleaf blackberry plant is effective in fighting off the bacteria Staphyloccus aureas, the cause of staph infections. The plant is used to treat skin conditions in southern Italy, and Quave discovered that its effectiveness is related to its ability to inhibit bacteria’s production of biofilm, a slimy matrix produced as a protective barrier. She continues to study the extract for its potential to shut down bacteria involved in other common infections in the ear and sinuses. Quave believes that it could be added to antibiotic drugs in the future to better treat resistant infections like the one she developed as a child.

In addition, Quave has launched two companies to bring potential drugs to market, and she was recently inaugurated into the National Academy of Inventors. She urged young scholars to consider nature-based drug development as a career path, noting that less than 1,000 of the more than 374,000 plant species on Earth have been examined for human health benefits.

“If you were born after the mid-1980s, no new class of antibiotic has been discovered and brought to market in your lifetime,” she said. “We really need to fill this pipeline, and my big question is, could plants be the solution? I’m a bit biased, but I think they could.”

(Lindsay Key is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)