NIEHS-funded researchers recently installed filtration systems in Native American communities to reduce exposure to and the health effects of arsenic-contaminated drinking water. Led by the Columbia University Northern Plains Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University, and in partnership with Northern Plain Tribal Nations and the Indian Health Service, the team installed arsenic filters under household kitchen sinks and launched a corresponding educational campaign.

“The intervention study was motivated by the finding that arsenic exposure in the Strong Heart Study — the largest and longest prospective study in American Indian communities — was associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, premature mortality, chronic kidney disease, and some forms of cancer,” said Ana Navas-Acien, M.D., Ph.D., who directs the Columbia University Northern Plains SRP Center.

Arsenic is a highly toxic, naturally occurring element commonly found in contaminated drinking water. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has established a safety limit of 10 micrograms of arsenic per liter for public water supplies. However, those regulations do not apply to private wells — the primary drinking water source for many rural communities, including Native American populations.

Community-informed study design

Navas-Acien and Christine George, Ph.D., of Johns Hopkins University, collaborated with colleagues at Missouri Breaks Industries Research, Inc., to design and implement the drinking water intervention in households participating in the Strong Heart Study in North and South Dakota. Missouri Breaks is a Native American-owned research organization that has worked with Tribal Nations for more than 25 years and leads the Strong Heart Study in those communities.

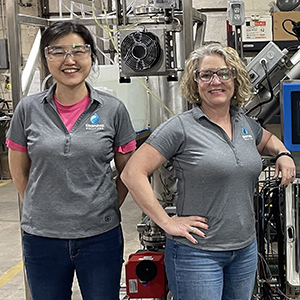

In collaboration with the Indian Health Service — a health care system for federally recognized Tribal Nations — and the Tribal Housing Authority, the team installed the arsenic filtration systems under kitchen sinks. They also provided households with a replacement cartridge and the manufacturer’s instruction manual on how to use the filter and change the cartridge.

The team randomly selected households for either simple or more intense educational support. Participants in the former group received phone calls at two weeks, three months, and five months after installation, reminding them to use the filter. Households selected for intensive support received the same phone calls, plus home visits one month and six months after installation.

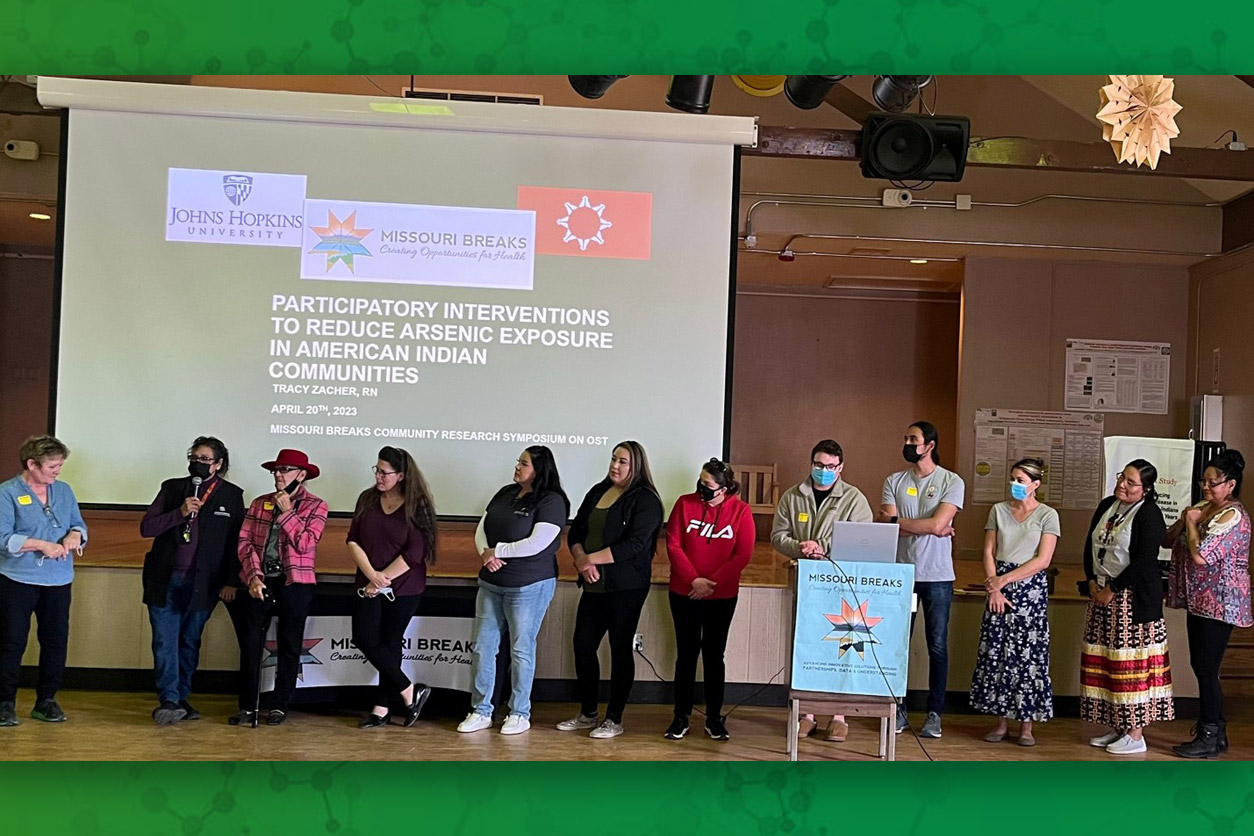

“We used phone calls, site visits, and videos to reinforce filter use and help families with installation and replacement," George said. “Every single step of our educational approach was developed with community input.”

Evaluating successes and barriers

To assess the effectiveness of the arsenic filters, the research team sampled filtered water and compared it to unfiltered water from other faucets in the household. They found that the filter successfully reduced arsenic concentrations to below the EPA limit in all households, with no difference between households that received simple or intensive support. Their results suggest that an intensive educational component may be unnecessary to ensure filter effectiveness.

A strength of the study, according to participants, was that the filters and educational interventions were delivered by trusted Tribal members familiar with the community customs and traditions. The researchers recommend that future interventions involve support networks, such as identifying a family member or neighbor who can help with filter changes.

“This intervention is an exemplary model that can help many other communities facing similar issues with arsenic contamination of drinking water in private wells,” said Tracy Zacher, who directed the fieldwork for Missouri Breaks.

“We are planning on continuing to support these efforts through community engagement, research translation activities, and planning new projects that can help scale up the efforts to provide arsenic-safe drinking water to the Northern Plains communities,” noted Zacher.

(Mali Velasco is a research and communication specialist for MDB Inc., a contractor for the NIEHS Division of Extramural Research and Training.)