During his Diversity Speaker Series lecture Antonio Baines, Ph.D., called for everyone to have a seat at the table to help find cures and solutions to many environmental health problems. The Feb. 23 lecture was sponsored by the Office of Science Education and Diversity in honor of Black History month.

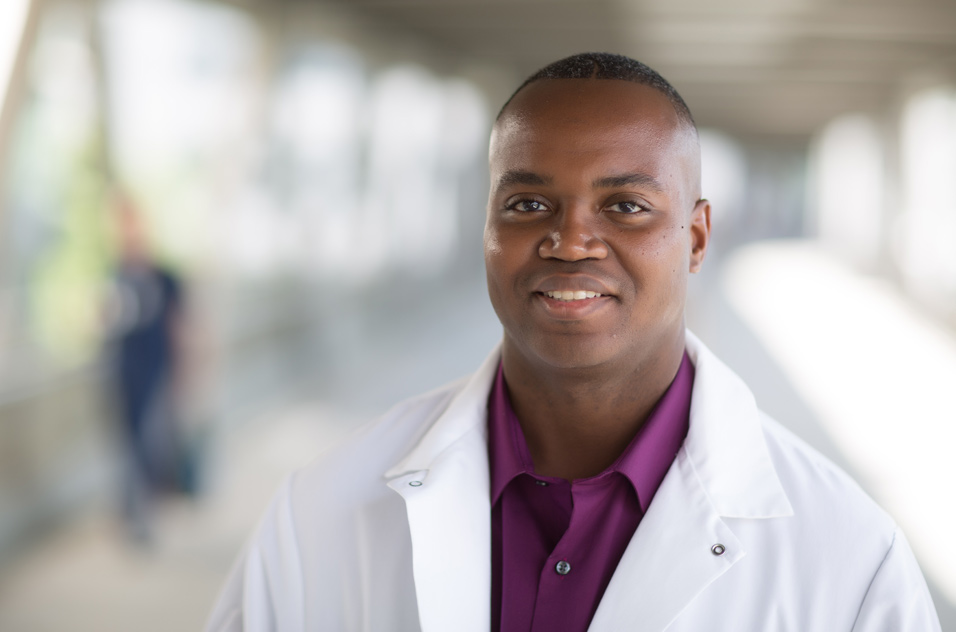

Baines is an associate professor in the Department of Biological & Biomedical Sciences at North Carolina Central University (NC Central) and an adjunct associate professor in the Department of Pharmacology and a member in the Curriculum in Toxicology and Environmental Medicine in the School of Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-Chapel Hill). He earned his undergraduate degree from Norfolk State University and became the second African American to earn a Ph.D. from the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Arizona.

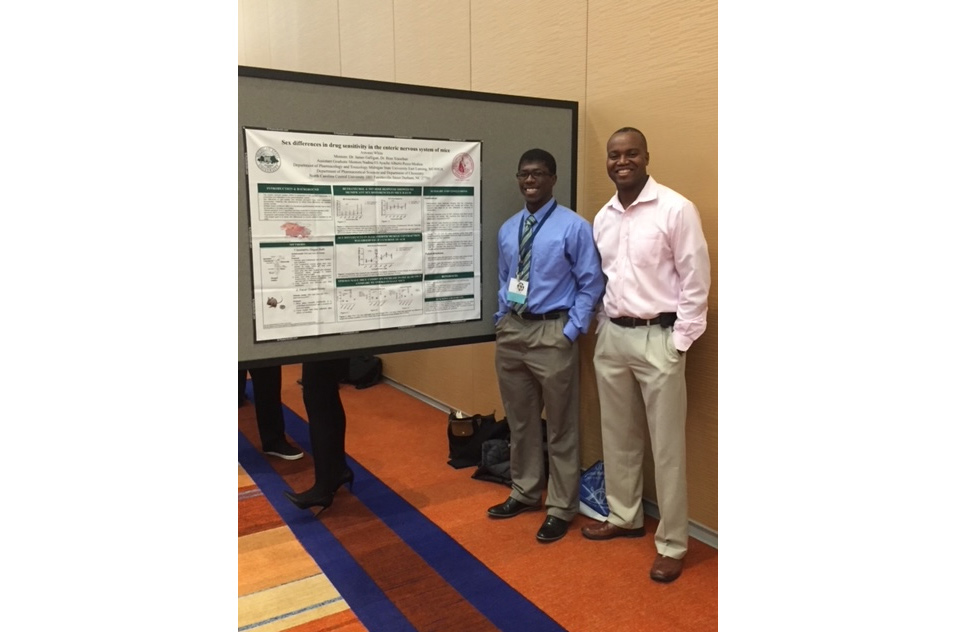

During his talk, Baines explained his current research efforts to alleviate drug resistance in pancreatic cancer and his passion for encouraging more students of color to take an interest in environmental health sciences. His energy and enthusiasm for teaching were evident as he described his research and the success his former students have achieved — from earning advanced degrees to teaching at top academic universities.

Before the lecture, Baines spoke with Environmental Factor about his academic and professional journey and his efforts to increase diversity among the next generation of environmental health researchers.

EF: Can you tell us about how your scientific journey began?

Baines: I grew up in a small town in rural Virginia. I always loved science, especially biology. What really put me on the path to making science a career was a high school biology teacher. He was like Robin Williams in “Dead Poets Society.” He once performed a chemistry experiment that blew holes in a light fixture. This and other experiences in that class really connected with my interest in science.

EF: There's nothing like blowing things up to get a teenager's attention.

Baines: Definitely. I was awarded a full STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] scholarship in a competitive honors program at Norfolk State University in Norfolk, Virginia, which is an HBCU [historically black college or university]. During my second year, I won a travel award to attend a Society of Toxicology meeting in New Orleans that changed my life. I met graduate students and professors from the University of Arizona. Ultimately, they helped me to decide that I wanted to go into toxicology and pharmacology. I wanted to be the one asking the questions and finding answers when it came to making novel drugs. In the University of Arizona Ph.D. program, I conducted research and wrote my dissertation on the chemoprevention of colon cancer. Then, I did a postdoc fellowship in the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at UNC-Chapel Hill studying pancreatic cancer.

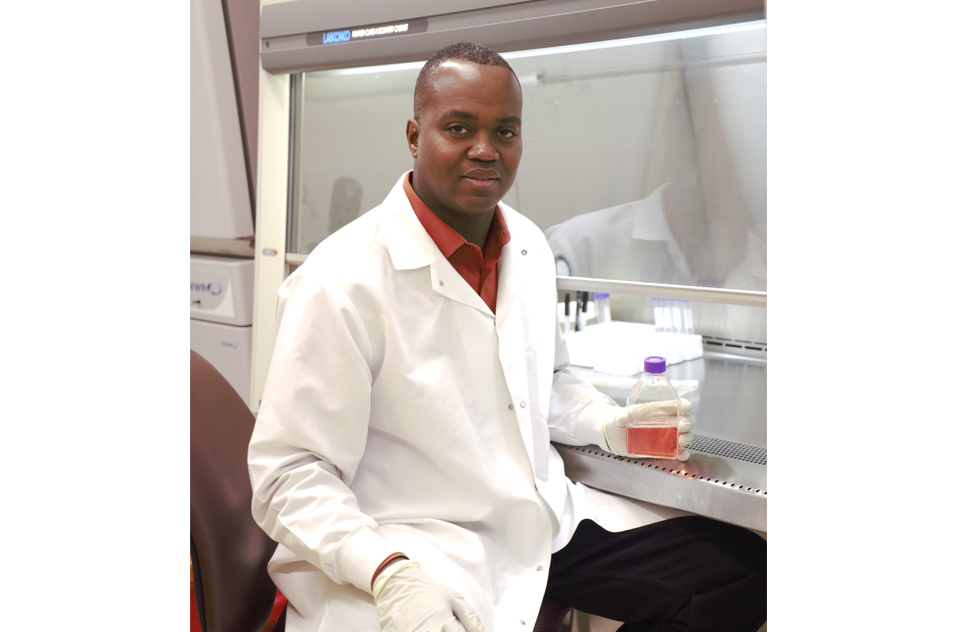

EF: How would you describe your work today?

Baines: I research novel drug targets and drugs that can potentially be used therapeutically against pancreatic cancer, which is the third most common cause of cancer deaths in the U.S. The five-year survival rate is just 12%. There’s also a health disparity issue. African Americans are diagnosed with more aggressive forms of the cancer and succumb to it more. Also, they are not as able to benefit from the limited treatments as other ethnic groups.

EF: What got you interested in trying to attract more young scholars of color to the environmental health sciences?

Baines: There's a disproportionately low number of people of color in the STEM field. I believe when everybody is at the decision table, benefiting from decisions, we will find treatments and cures for diseases, such as cancer, much quicker. Also, minority groups disproportionately live in environmentally hazardous areas. With diversity, folks who do environmental health research can help decrease environmental racism and increase justice.

EF: Tell us about your 21st Century Environmental Health Scholars program?

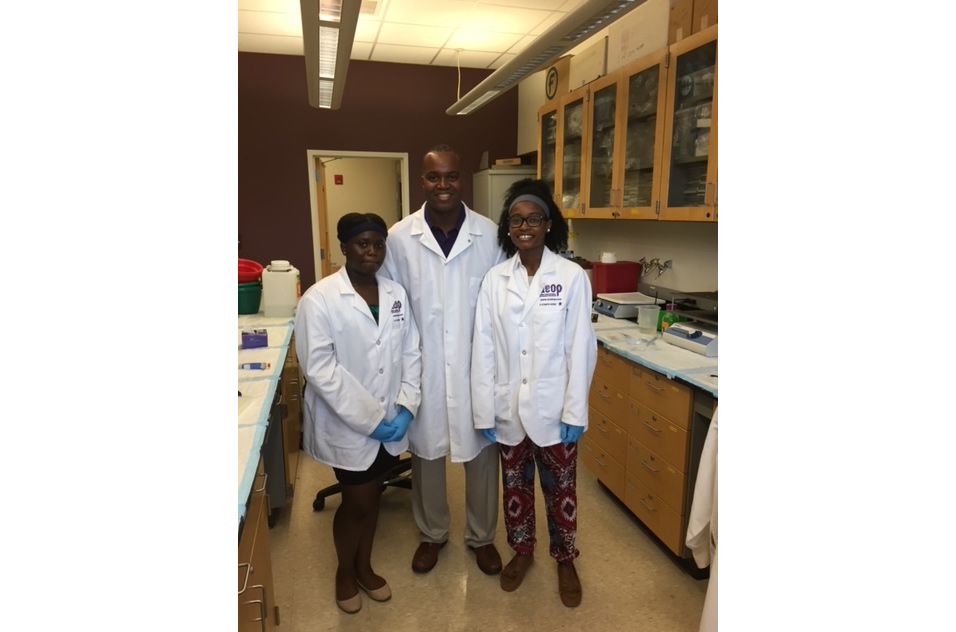

Baines: With this collaboration, diverse students from NC Central and UNC-Chapel Hill conduct environmental health sciences and toxicology research and participate in professional development opportunities between both universities. Many come to us unfamiliar with what environmental health is and why it matters. Our goal is to expose them to the field with the hope that some will make it their career. Most of the scholars in the program who have completed the program and graduated go on to graduate school, including Ph.D. programs, or medical school.

EF: What led to your joint appointment?

Baines: My goal was to have an academic and scientific career at a small institution, but still be connected to a larger research institution. Although I teach and mentor students at UNC-Chapel Hill, especially minority students, my primary responsibilities of teaching and research are at NC Central, an HBCU. For me, it's the best of both worlds, but I enjoy having an impact on students no matter where they are and who they are.

(John Yewell is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)