Texas A&M University scientists developed a skin cream that may protect people from contaminants in floodwaters, such as benzene, toluene, and xylene. The cream, which forms a barrier between human skin and contaminants, is the culmination of several studies, partially funded by the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (SRP), which have explored materials that can adsorb and immobilize toxicants to reduce human exposures.

A mixture of benzene, toluene, and xylene (BTX) is used in oil refining and gasoline formulation. Exposure to these chemicals can harm the nervous system and has been linked to some cancers, including childhood leukemia.

Flooding caused by natural disasters can move contaminants such as BTX from industrial sources to more populated areas. Human skin also becomes more porous, weakening its ability to block pollutants, the longer it is in contact with water. Although personal protective equipment (PPE) can prevent some exposures, more tools are needed to further protect people near disaster sites.

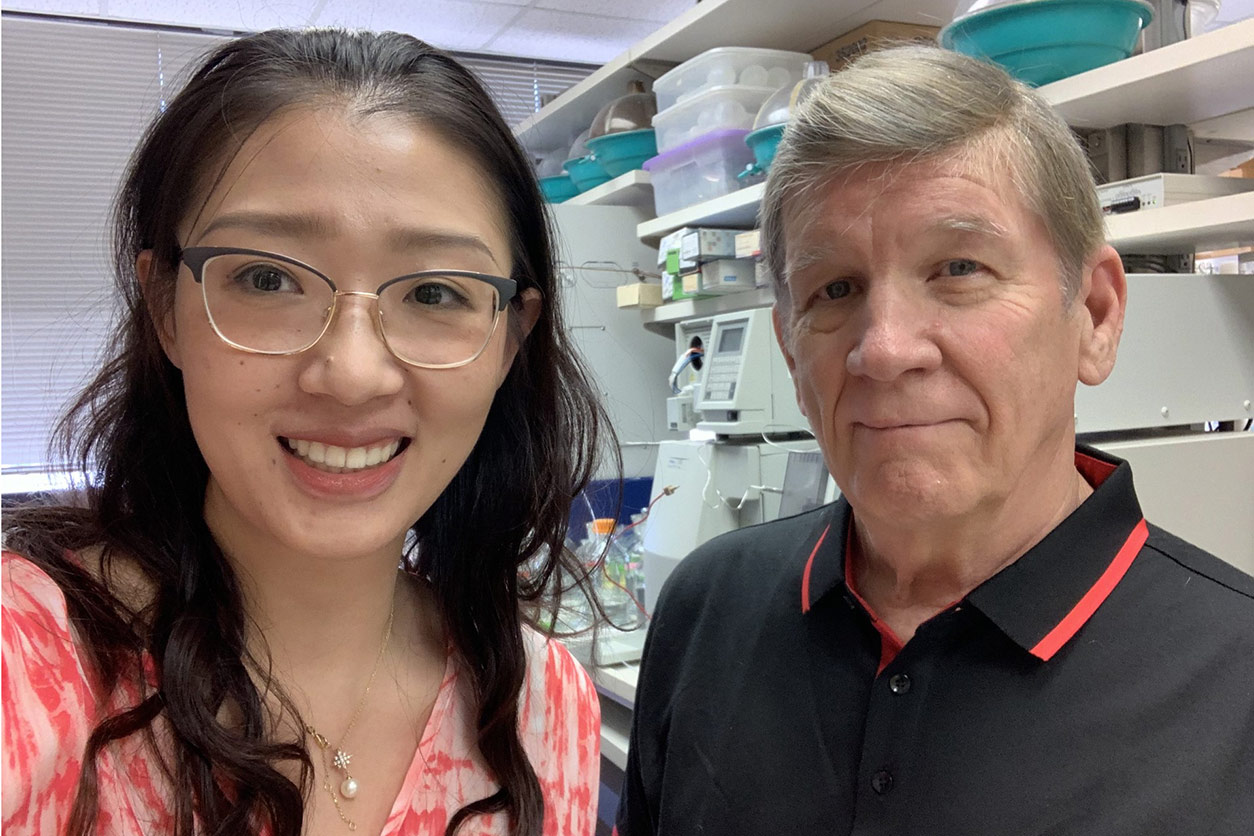

“There is a critical need for protective measures against BTX,” said Meichen Wang, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow and SRP trainee. “This barrier cream can be a new approach for preventing exposure through the skin.”

SRP solutions

Wang co-led the study with principal investigator Tim Phillips, Ph.D. Together, they have worked on a variety of sorbents — materials that can attract and adsorb certain molecules — to be used by people working at disaster sites. They previously studied how montmorillonite clay mixed into a base cream could block chemicals dissolved in water from penetrating the skin.

Wang and Phillips, with Ph.D. student Kelly Rivenbark, also developed a chlorophyll-amended clay. When added to clay, chlorophyll — a compound that gives plants their green color — enhanced the clay’s ability to bind benzene in water.

The researchers analyzed how well the cream bound BTX within a four-hour period, which is the average length of a first responder’s shift. Compared to clay-only barrier creams, the chlorophyll cream adsorbed more BTX for a longer period. The barrier cream also protected aquatic plants and animals from the effects of BTX when the cream was added to their environment.

A new kind of protection

The Phillips lab is still improving the cream and studying sorbents with different properties. The team is exploring antimicrobial additives, and Wang is researching natural additives that can block heavy metals. The lab plans to formulate a barrier cream that protects against a variety of contaminants, including PFAS and E. coli bacteria.

“This cream can be tailored for different scenarios,” Wang said. “It can be paired with PPE to provide more protection for vulnerable communities and first responders during disasters. I think it represents an advancement in environmental remediation.”

(Michelle Zhao is a science writer for MDB, Inc., a contractor for the NIEHS Division of Extramural Research and Training.)