Mobile applications have enhanced our lives in a multitude of ways. They enable us to translate languages, get directions to avoid traffic delays, and learn about the plants and animals in our backyards. Mobile apps can also be used to advance environmental justice, according to research presented Aug. 23 during a webinar hosted by the NIEHS Partnerships for Environmental Public Health (PEPH) network.

The webinar was the second of two PEPH sessions featuring NIEHS grantees and their efforts to develop mobile apps that improve environmental public health. Researchers shared how they partnered with community members in Chicago, Southern California, and Flint, Michigan, to devise apps that enable them to track and report a variety of environmental exposures.

“The projects highlighted in this two-part series exemplify the innovative work taking place in partnership with community residents and workers,” said moderator Liam O’Fallon, health specialist in the Population Health Branch. “The PEPH webinar series is a valuable platform to raise awareness of efforts to advance environmental public health.”

A tool for empowerment

To report environmental concerns such as spilled oil or strange odors, Chicago residents have historically called 311, the number for non-emergency services. But the wait times can be between 45 and 90 minutes, and there is often no follow-through from the city, according to Nadia Pack, program manager for the ChicAgo Center for Health and EnvironmenT (CACHET).

Pack said the idea for an app came from members of the Southeast Environmental Task Force Community Advisory Board in Chicago, who felt there must be an easier way for residents to report environmental issues they witnessed in their communities.

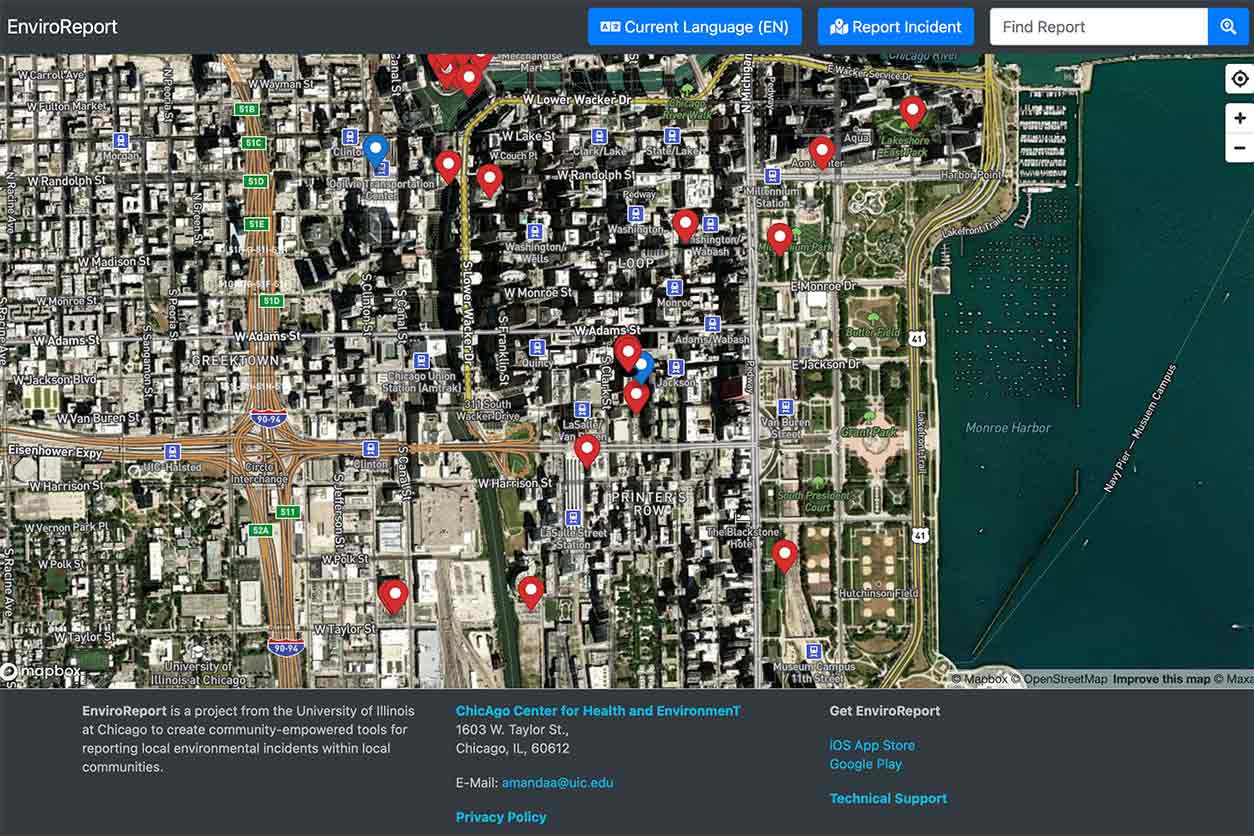

The solution that CACHET Community Engagement Core leader Victoria Persky, M.D., came up with was the development of EnviroReport, a mobile app with reporting capability that could lead to a more timely resolution of individual and community concerns. CACHET partnered with Jill Johnston, Ph.D., from the Southern California Environmental Health Sciences Center, to refine the app, build training programs in English and Spanish, and test it in environmental justice communities in Chicago and Los Angeles.

“There are disasters happening regularly in our communities, such as a warehouse catching fire, yet we don’t have an aggregate source to understand where all these hazards happened,” said Johnston. “This creates a way for the community to collect that data and further identify places where regulatory agencies need to take additional action.”

Community as collaborators

The Flint, Michigan, water crisis was one of the most publicized environmental incidents in recent American history. According to Jennifer Carrera, Ph.D., from Michigan State University, the stories of the water crisis often portray the community members merely as victims, but the residents were not passive.

“They played a leading role in drawing attention to the disaster and holding institutions accountable,” said Carrera.

Carrera has been working with Flint residents since 2015, after the community's water supply was contaminated in 2014. She was awarded an NIEHS Transition to Independent Environmental Health Research Career Award in 2018 to work with community partners to develop low-cost tools for community environmental monitoring. Through preliminary focus groups prior to grant submission, Carrera's team discovered that residents were more interested in how this information was going to be shared within the community than any specific tools for testing.

“So, we shifted from thinking about low-cost technologies for testing to developing a mobile application to allow for true community control over the data collection and sharing process,” said Carrera.

Carrera coded the mobile application, working with a core leadership team of six Flint residents and a group of 26 additional residents to develop, test, and refine the app.

“The really exciting thing that came out of these conversations was an evolution in thinking about why this work was important,” said Carrera.

For example, one resident initially questioned why the city was not doing water testing (which it was, but not all residents trusted the results). By the end of the pilot, that same resident said it was important to engage more community members in the process of evaluating the safety of their own water.

“The group came to the conclusion that participating in science is an act of democracy,” said Carrera.

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)