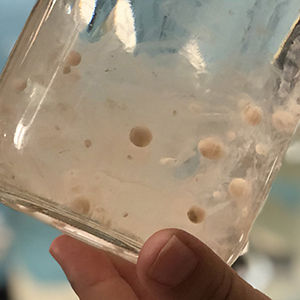

Using data from the United States and Brazil, NIEHS grantees have unearthed the genetic basis for the production of guanitoxin, an important cyanotoxin produced by freshwater harmful algal blooms (HABs). Their findings could help researchers around the world understand, monitor, and mitigate HABs, which are overgrowths of toxin-producing algae that can create dangers for both human and animal health.

Moore’s research interests include marine biomedicine, biotechnology, microbial genomics and metabolomics, natural product drug discovery, natural toxins and pollutants, and synthetic biology. (Photo courtesy of Erik Jepsen, UC San Diego)

Moore’s research interests include marine biomedicine, biotechnology, microbial genomics and metabolomics, natural product drug discovery, natural toxins and pollutants, and synthetic biology. (Photo courtesy of Erik Jepsen, UC San Diego)“We really opened the black box of this mostly unmonitored toxin’s cell production,” said NIEHS grantee Bradley Moore, Ph.D., from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California at San Diego (UC San Diego). “Having this new knowledge of the functions and roles of each and every gene involved in creating this most potent of freshwater neurotoxins, guanitoxin, gives us knowledge for the future — on what organisms carry those genes and if there are environmental factors that initiate producing [that toxin].”

The research was published May 18 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. The work involved other researchers from Scripps, the University of California at Santa Cruz, and the University of São Paulo, Brazil. Moore and fellow NIEHS grantee Timothy Fallon, Ph.D., also from Scripps, are co-authors. NIEHS and the São Paulo Research Foundation were among the institutions that funded the study.

Making guanitoxin easier to detect

Although public health agencies monitor most toxins that cause HABs, guanitoxin is not presently environmentally monitored. Standard analytical methods cannot easily detect the toxin, partly because chemical instability causes it to degrade quickly. And, until now, scientists did not know guanitoxin’s genetic composition or how to track it in water.

One of the most lethal cyanotoxins, it affects the nervous system.

If a dog jumps in water with floating scum that produces guanitoxin or another deadly toxin, such as saxotoxin, that healthy pet could be dead hours later.

“A lot of these events are mysterious,” said Moore. “It’s encouraging that there’s a chance now to test for guanitoxin in the water.”

Yet, standard compounds for guanitoxin or its degradation products were and are not commercially available, making direct tests for guanitoxin hard to develop, noted Moore. The researchers designed new synthesis methods to produce these molecules, and the scientists plan to make them available to the cyanotoxin research community.

Mapping toxicity

Moore’s Brazilian colleagues sequenced the genome of a guanitoxin-producing cyanobacterium isolated from a reservoir in Brazil. The combined group then found and validated the cluster of genes and nine enzymes that cause an amino acid, arginine, to convert into guanitoxin.

Fallon, analyzing environmental sequencing data sets from Wisconsin, Ohio, and Brazil, found that the genes responsible for guanitoxin biosynthesis repeatedly show up in municipal freshwater that has experienced past toxic algal blooms.

They also discovered that two cyanobacterial groups not previously known to produce guanitoxin — Cuspidothrix and Aphanizomenon — actively express the toxin biosynthesis genes.

Planning for HABs

Now that the Scripps team has mapped guanitoxin’s genetic source, they hope researchers can use that knowledge to monitor guanitoxin in inland waters around the world.

“Toxic hotspots of algal blooms that might include guanitoxin seem to be a global problem, not just in North America or Brazil,” said Fallon. “This toxin is also in Europe and Asia, as far as we can assume. We don’t yet have hard data on that, but we’re hoping this new genetic information will allow researchers elsewhere to conduct their own analyses and add to known information.”

“As we gather more data from around the world, we’ll be able to look at annual patterns and understand in advance what each year will bring us,” Moore added.

Fallon aims to perfect an environmental molecular diagnostic assay for the genes that play a role in producing guanitoxin. A company already has licensed their technology, Moore said.

The genetic finding will help with advance planning, according to Anika Dzierlenga, Ph.D., who directs the NIEHS Oceans and Human Health Program.

“As climate change continues to increase HAB events around the country, it is great to develop new approaches that help predict whether such events will be particularly toxic,” she said. “Getting ahead of the situation is critical, which is why this research is so important.”

Citation: Lima ST, Fallon TR, Cordoza JL, Chekan JR, Delbaje E, Hopiavuori AR, Alvarenga DO, Wood SM, Luhavaya H, Baumgartner JT, Dörr FA, Etchegaray A, Pinto E, McKinnie SMK, Fiore MF, Moore BS. 2022. Biosynthesis of guanitoxin enables global environmental detection in freshwater cyanobacteria. J Am Chem Soc; doi:10.1021/jacs.2c01424 [Online 18 May 2022].

(Catherine Arnold is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)