NIEHS grantees Mark Hahn, Ph.D., and John Stegeman, Ph.D., contributed to a recently released study focusing on how plastics may affect ocean and human health. Stegeman directs the Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health, which is jointly funded by NIEHS and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Stegeman and Hahn were part of a first-ever collaboration with healthcare, ocean science, and social science researchers to quantify plastics’ considerable risks to all life on earth. The resulting Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health report published on March 21 is a comprehensive analysis showing plastics as a hazard at every stage of their life cycle.

“It’s only been a little over 50 years since we’ve been aware of the presence of plastics throughout the ocean,” said Stegeman, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). “The Minderoo-Monaco Commission’s work is a significant leap forward in connecting the broad health implications of plastics to the ocean and to humanity.”

The report was led by scientists at the Minderoo Foundation, the Centre Scientifique de Monaco, and Boston College. Philip Landrigan, M.D., a longtime NIEHS grantee, co-led the overall Commission producing the report. Hahn and Stegeman were lead authors on the section focusing on plastics’ effects on the ocean.

Key findings

“This report summarizes decades of work, shedding new and important light on global public health issues related to marine plastic pollution,” said Anika Dzierlenga, Ph.D., who oversees the NIEHS grant that supports the Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health.

The Commission’s key findings include the following.

- Plastics may cause disease, impairment, and premature mortality at every stage of their life cycle, with the health repercussions disproportionately affecting vulnerable, low-income, and minority communities, particularly children.

- Toxic chemicals that are added to plastics and routinely detected in people are known to increase the risk of miscarriage, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and cancers.

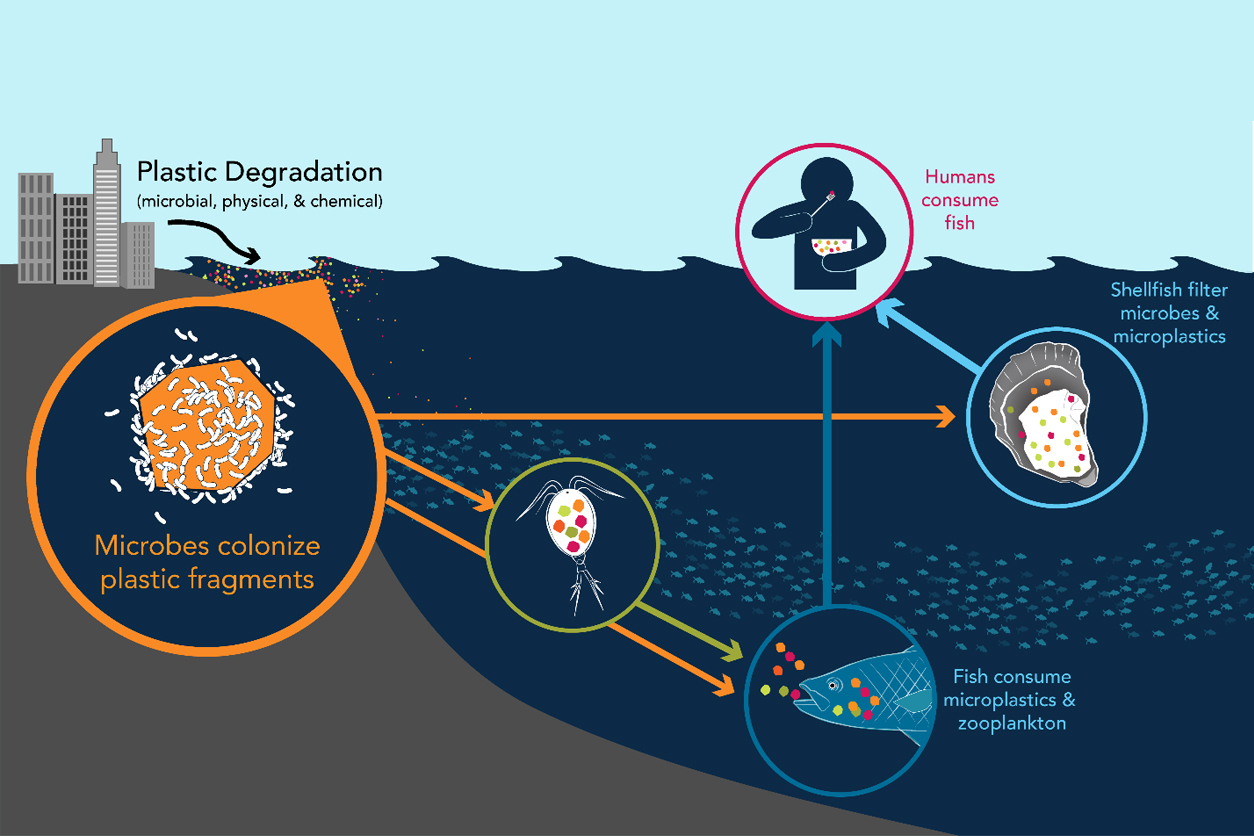

- Plastic waste is ubiquitous in the global environment, with microplastics occurring throughout the ocean and the marine food chain.

- There is a need for better information about the concentrations of the smallest micro- and nano-plastic particles in the marine environment and their potential impacts on marine animals and ecosystems.

Environment and health costs

The Commission concluded that current plastic production, use, and disposal patterns are not sustainable and are responsible for significant harm to human health, the economy, and the environment — especially the ocean — as well as deep societal injustices. Plastics, the report notes, account for an estimated 4%-5% of all greenhouse gas emissions across their lifecycle, making them a large-scale contributor to climate change.

The study also calculated health costs attributed to plastic production to be $250 billion in a 12-month period, which is more than the gross domestic product of New Zealand or Finland in 2015. In addition, health care costs associated with chemicals in plastics are estimated to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars. The researchers also noted that the ubiquity of fast food and discount stores in poorer communities increased residents’ exposure to plastic packaging, products, and associated chemicals.

Next steps

As a result of its findings, the Commission recommends that a cap on global plastic production be a defining feature of the Global Plastics Treaty currently being negotiated at the United Nations. The Treaty should address the impacts of plastics across their entire life cycle, including the many thousands of chemicals incorporated into plastics and the human health impacts. Many potential harms from plastics can be avoided through better production practices, alternative design, use of less toxic chemicals, and decreased consumption, according to the Commission.

“Ocean health is intimately and intricately connected to human health,” said Hahn, a senior scientist at WHOI. “Our attention now needs to be on creating a broadly acceptable international agreement that addresses the full life cycle of plastics in order to prioritize the health of the ocean that supports us all.”

(This article is adapted from a March 21 press release by WHOI.)

(Caroline Stetler is Editor-in-Chief of the Environmental Factor, produced monthly by the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)