Remote geospatial technology generates data that offer precision insights to environmental health scientists and decisionmakers. The experts who gathered for the latest workshop by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) discussed how geospatial data may improve exposure estimates. The April 14-15 meeting, co-sponsored by NIEHS, connected those who produce geospatial data with users of their output.

“Place really matters for health,” said Susan Anenberg, Ph.D., from The George Washington University (GWU). Anenberg chaired the workshop’s organizing committee.

NIEHS and National Toxicology Program Director Rick Woychik, Ph.D., gave opening remarks. He described the enormous challenges involved in estimating the exposome, or the sum of all exposures a person experiences across the life span. “It’s becoming clear that geospatial information can provide a powerful enhancement to the way that we collect environmental exposure data,” he said.

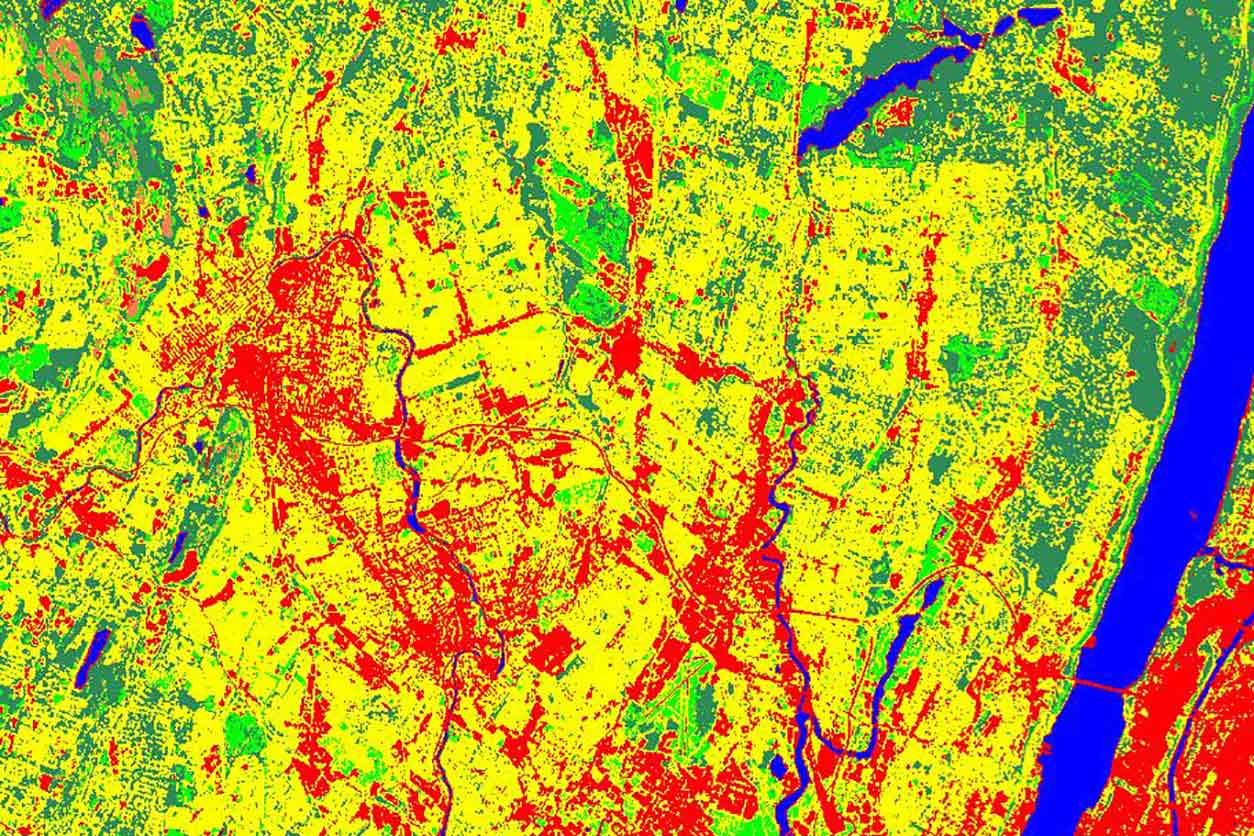

The Paterson, New Jersey area, taken by Landsat 7, from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), shows land cover as Red: heavily urbanized; Yellow: low intensity residential; Light Green: urban, recreational, grasses; Green: forests; Blue: water; Coral: bare soil, rock. (Image courtesy of the NASA-funded Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center at Columbia University)

The Paterson, New Jersey area, taken by Landsat 7, from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), shows land cover as Red: heavily urbanized; Yellow: low intensity residential; Light Green: urban, recreational, grasses; Green: forests; Blue: water; Coral: bare soil, rock. (Image courtesy of the NASA-funded Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center at Columbia University)More than pollution, genetics

As several of the speakers highlighted, health is more than just pollution and genetics. Anenberg noted that geospatial technologies open new avenues in environmental health, from novel epidemiological approaches to forecasting extreme weather.

Anenberg explained that remote sensing of microenvironments and individual behaviors helps scientists move toward individual-level exposure data, risk models, and interventions. (Photo courtesy of Susan Anenberg)

Anenberg explained that remote sensing of microenvironments and individual behaviors helps scientists move toward individual-level exposure data, risk models, and interventions. (Photo courtesy of Susan Anenberg)- The distribution of pollution levels and vulnerability in the underlying population influence environmental health inequities.

- Advances in remote sensing and personal monitors of environmental conditions and behavior take exposure science down to the individual level.

- Electronic health records expand the amount and type of anonymized health data available for environmental health studies.

- Satellite data and geospatial models can help communities prepare for and respond to extreme weather and other disasters.

The confluence of heightened awareness about environmental health risks and environmental injustice, coupled with widening availability of different types of remote geospatial technologies, make this the right time to foster the transdisciplinary collaborations needed to make the best use of geospatial data, Anenberg said.

Equity moves to forefront

Organizers invited two keynote speakers. Cecilia Martinez, Ph.D., the White House Council on Environmental Quality senior director for environmental justice, discussed a new program called the Justice40 Initiative. The government-wide effort aims to deliver 40% of the overall benefits of federal investment in clean energy to disadvantaged communities.

“Equity and justice, as part of climate and energy, is a relatively immature field,” she said. “My role is to make sure equity is front and center ... in decision-making tools and in the data portals.” She further stressed the importance of community engagement and building trust between scientists, government representatives, and community members.

Spatial patterns matter

Keynote speaker Marie Lynn Miranda, Ph.D., from the University of Notre Dame, focused on four concepts.

- Health is spatially patterned, in terms of trends, disease statistics, and other health indicators.

- Contributions to health — such as green space, industrial exposures, water quality, and access to fresh food — are spatially patterned.

- Health care access — how far is the nearest dentist or mental health professional? — is spatially patterned.

- Scale matters when looking at data. State, county, and zip code level data tell different stories.

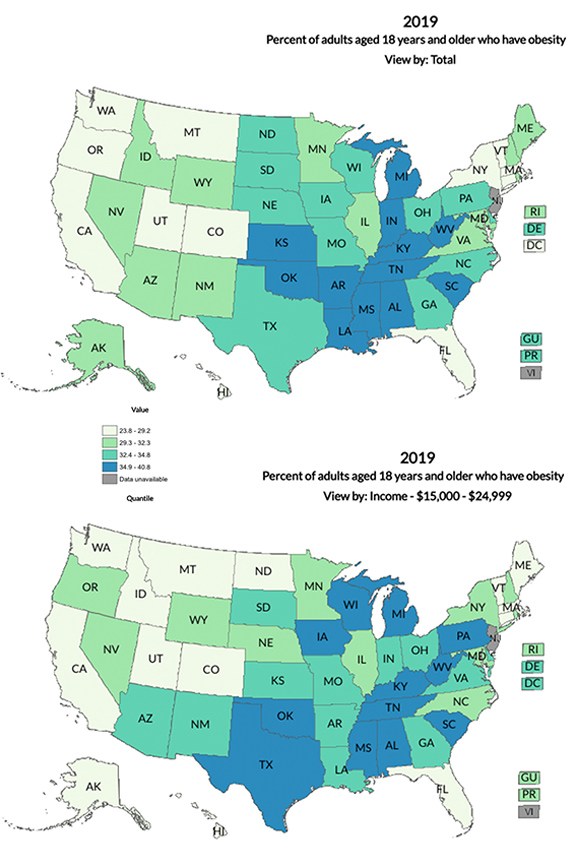

Besides geography, scale matters in demographic and other data. Obesity rates in New York, Arkansas, Alaska, and other states change when all adults are counted instead of only those at certain income levels. (Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Besides geography, scale matters in demographic and other data. Obesity rates in New York, Arkansas, Alaska, and other states change when all adults are counted instead of only those at certain income levels. (Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)Satellites transmit data on vegetation, temperature, urban development, air pollutants, and more. In addition, scientists may draw on data from wearable sensors, mobile phone tracking, and administrative records collected by various government entities. “What geospatial data makes possible is precision medicine at scale,” Miranda explained.

The way forward

“We need to be training public health professionals to use geospatial data, and we need to train geospatial data developers and analysts on the problems that data can be used for,” Miranda noted.

Melissa Perry, Sc.D., co-chair of the NASEM Emerging Science for Environmental Health Decisions Committee, charged participants to think ahead. “Take time to look into the future: what aspirational goals do we want to set and where would we like to be in three to five years?” she said. Perry chairs the GWU Department of Environmental and Occupational Health.

She encouraged fostering multidisciplinary collaborations; innovating the research training enterprise; improving funding success of grants that use geospatial methods, especially with respect to community partners; and reducing structural racism and environmental injustices.

Videos and a summary report will be posted to the meeting website in the coming months.