A documentary titled “Air, Water, Blood: The Power of Community-Engaged Research,” funded through an NIEHS grant, was broadcast at the American Public Health Association Public Health Film Festival Oct. 24-27. It features the work of Clare Cannon, Ph.D., who is using a community-based participatory research approach (see sidebar) to address environmental health concerns of residents living in Kettleman City, California, which is an agricultural town.

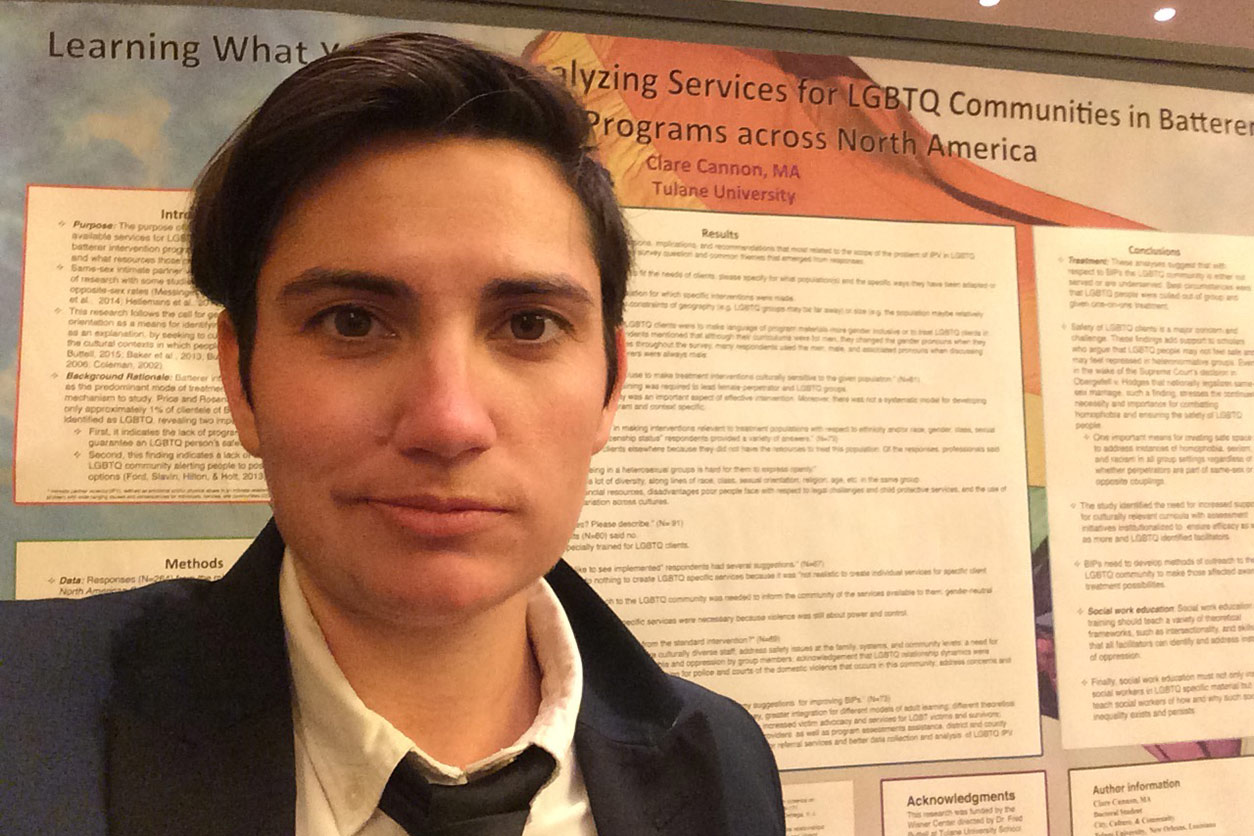

Cannon is an assistant professor of community and regional development at the University of California, Davis. (Photo courtesy of Clare Cannon)

Cannon is an assistant professor of community and regional development at the University of California, Davis. (Photo courtesy of Clare Cannon)Through a pilot grant from the NIEHS-funded Environmental Health Sciences Center at the University of California, Davis (UCD), Cannon and her partners in the community brought attention to potential negative health effects of a class 1 hazardous waste landfill located in the majority Latino, primarily Spanish-speaking town.

Air, Water, Blood: The Power of Community-engaged Research

PCBs, pesticide runoff, and diesel fumes

The dump is the only one in the state approved for the disposing of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which are found in products such as adhesives, oil-based paint, insulation, and electrical equipment. The substances are no longer commercially produced in the United States, but they persist in the environment. In humans, PCBs are considered probable carcinogens, and they have been linked to health issues such as diabetes, liver toxicity, and adverse effects on skin, as well as immune, neurological, and respiratory dysfunction.

According to Cannon, some Kettleman City residents suspect that they also have been affected by pesticide runoff and diesel fumes.

Cannon worked closely with Maricela Mares Alatorre and her son, Miguel, both of whom are community organizers for Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice. For the Alatorres, such organizing aligns with family tradition. Maricela’s parents formed a group called People for Clean Air and Water of Kettleman City in the early 1990s to stop the installation of a proposed toxic waste incinerator in the town.

From left, Miguel Alatorre gives a tour of Kettleman City to Jonathan London, Ph.D., co-director of the Community Engagement Core (CEC) at the UCD Environmental Health Sciences Center, and Aubrey Thompson, former associate director of CEC, pointing out potential sources of pollution. (Photo courtesy of Clare Cannon)

From left, Miguel Alatorre gives a tour of Kettleman City to Jonathan London, Ph.D., co-director of the Community Engagement Core (CEC) at the UCD Environmental Health Sciences Center, and Aubrey Thompson, former associate director of CEC, pointing out potential sources of pollution. (Photo courtesy of Clare Cannon)By the people, for the people

After a rash of birth defects and infant mortality affected the town from 2007 to 2009, the community lobbied the state to conduct testing to determine the cause. In 2016, the state released a study that reported no conclusive evidence of area pollution contributing to the birth defects. Some Kettleman City residents said they felt their concerns and their knowledge of the community had been ignored in the study.

In 2019, enter Cannon, a sociologist by training.

“My role is clearly to do the science and to put the science, made as accessible as possible, in the hands of the community,” she said. “They’re the experts on their community, they’re the advocates for themselves, and they’re good at movement building.”

To work with the people of Kettleman City, Cannon conducted interviews with residents and tapped the expertise of researchers from other disciplines at the UCD Environmental Exposure Core. They sought to study air pollution from volatile organic compounds and analyze residential water for benzene and arsenic. The team also took blood samples to test for PCBs.

Results showed high levels of particulate matter and carbon in the town’s air — indicators of diesel pollution. Although the study showed no direct signs of benzene, there is evidence of benzene derivatives. In addition, arsenic levels in residential wells that were sampled exceeded federal limits. The blood sample testing for exposure to PCBs is still ongoing.

Protecting vulnerable communities

“Having data like this in our hands is so powerful,” Maricela said in the documentary. “It validates our concerns, and it gives us something to be able to work with policymakers [who] don’t take us seriously,” she added.

“This is the first time that someone really showed true compassion and a real [desire] to figure out what’s going on here in Kettleman and give us results,” said Miguel.

The Alatorres and others are working with Cannon on a policy brief and fact sheet about the pilot study’s findings.

Cannon has applied for further funding from the National Institutes of Health to continue the study, which uses a transdisciplinary approach to address environmental health issues.

“Our work isn’t possible without people like Maricela and Miguel, who work day in, day out to improve health in their communities and reduce environmental injustice,” she said.

“Centers like the one at Davis really matter,” Cannon added. “Without linking partners, researchers, expertise, and the equipment of core investigators, this work can’t happen. Our transdisciplinary approach will become increasingly important to protect vulnerable communities experiencing environment injustice, particularly as we see more climate change effects.”

Citation: Cannon CEB. 2020. Towards convergence: How to do transdisciplinary environmental health disparities research. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(7):2303.

(Kelley Christensen is a contract editor and writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)