Humphrey Yao, Ph.D., head of the NIEHS Reproductive Developmental Biology Group, presented a webinar for institute researchers titled “How to Write a Scientific Manuscript” on April 7. He offered tips on crafting clear and compelling papers, and advice on choosing journals in which to publish.

Environmental Factor sat down with Yao, who in 2018 was awarded tenure by the National Institutes of Health, to learn more about his approach to scientific communication — and his path to NIEHS.

“I have always loved to do comparative biology because I don’t think understanding only one species tells the whole story,” said Yao. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

“I have always loved to do comparative biology because I don’t think understanding only one species tells the whole story,” said Yao. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)EF: You have published more than 60 papers, many in top science journals, and you serve on various editorial boards. How has this experience informed your writing advice?

Yao: I have learned that if we only write for other experts, the value of our research is minimal. If I just present facts and data, others may not be able to appreciate my paper because it is too dry. That includes scientists who are not in my field. So, I try to show the importance of developing a story — a scientific narrative that is engaging and easy to understand.

Another lesson came early in my career, as a faculty member at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign [UIUC]. I applied for an internal grant but was declined. I remember a comment from a reviewer saying that I was not a good hire for the university because I did not have high-profile publications.

Some people think that the only good scientists are those with papers in top journals, such as Science and Nature. But what is important is doing great science, coming up with novel ideas, and testing them. You earn respect by conducting quality research, no matter where you publish.

EF: Can you talk about your career path and how you came to NIEHS?

Yao: In Taiwan, where I was born, males must serve two years in the military, so I did that after college. Then I found a job translating English literature to Chinese. I probably picked up the skill from my mother, who is artistic and speaks multiple languages.

But in college, I had been intrigued that different animals use different mechanisms to produce eggs and sperm. So, I pursued a doctoral degree in animal sciences and reproductive biology, eventually coming to America and earning my Ph.D. from [UIUC]. My mentor, Dr. Janice Bahr, taught me how to become a true scientist. She changed my life for the better.

My postdoctoral training was at Duke University, in the lab of Dr. Blanche Capel. I studied whether animals have common biological mechanisms that determine sex. After three years, I went back to [UIUC], joining the faculty. I used mouse models to learn how the ovary forms in the embryo. I also taught veterinary students histology, anatomy, and reproductive biology.

At a scientific meeting, I met Dr. Carmen Williams, deputy chief of the NIEHS Reproductive and Developmental Biology Laboratory. She told me about a job opening at the institute. I came to NIEHS for an interview, and I was very impressed, especially by the quality of the research and resources available to scientists here. Fortunately, the institute appreciated my work and offered me a position in 2010.

EF: What does your lab focus on?

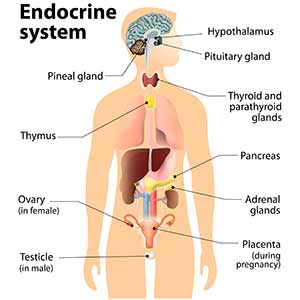

Yao: A major issue humans face involves defects in reproductive organs during fetal development. Hypospadias, in which the opening of the urethra is on the underside of the penis instead of at the tip, is an example. It is one of the most common birth defects. Genetic factors are involved, but we also know that if we expose pregnant mice to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, males can develop this disorder.

Our lab uses animal models to better understand that condition and other reproductive diseases, and to determine whether chemical exposures in development may affect people later in life.

Citations:

Nicol B, Grimm SA, Chalmel F, Lecluze E, Pannetier M, Pailhoux E, Dupin-De-Beyssat E, Guiguen Y, Capel B, Yao HHC. 2019. RUNX1 maintains the identity of the fetal ovary through an interplay with FOXL2. Nat Commun 10(1):5116.

Zhao F, Franco HL, Rodriguez KF, Brown PR, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY, Yao HHC. 2017. Elimination of the male reproductive tract in the female embryo is promoted by COUP-TFII in mice. Science 357(6352):717–720.

(Jesse Saffron, J.D., is a technical writer-editor in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)