“These AFFFs are used in a 3-6% concentration in either fresh or sea water when they are put in big tankards to fight fires,” said Mauge-Lewis. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

“These AFFFs are used in a 3-6% concentration in either fresh or sea water when they are put in big tankards to fight fires,” said Mauge-Lewis. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Chemical mixtures used in firefighting were the focus of a March 30 webinar sponsored by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s (UNC) graduate toxicology and environmental medicine program. Kevin Mauge-Lewis, an NIEHS Intramural Research Training Award fellow, said there is concern that use of aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) may lead to adverse human health effects.

AFFFs consist of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), detergents, other chemicals, and water. That blend creates a sudsy layer over flames, cutting off oxygen and extinguishing them. The foams are widely used at U.S. military bases, airports, and chemical plants, among other places, to put out fuel-based fires. Runoff from those sites has contaminated groundwater, soil, and surface water.

Mauge-Lewis works in the Division of the National Toxicology Program (NTP) Reproductive Endocrinology Group, which is led by Sue Fenton, Ph.D. They seek to better understand any potential health effects of new-generation AFFFs, which were created to replace the older formulations that contained legacy PFAS.

Biologically persistent

Early versions of AFFFs, first produced in the 1960s, contained a PFAS called perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). The chemical later became cause for concern.

“That substance is itself an environmental contaminant,” said Mauge-Lewis. “It is not produced anymore in the U.S., and emissions have been reduced, but it is biologically persistent. It has a strong carbon-fluorine backbone that doesn’t degrade very well in the human body or in the environment,” he explained.

“Military bases have drinking water wells of their own, and these chemicals can get down into the groundwater that feeds those wells,” said Fenton. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

“Military bases have drinking water wells of their own, and these chemicals can get down into the groundwater that feeds those wells,” said Fenton. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)PFOS and another chemical, perfluorooctanoic acid, are two of the most well-studied PFAS, according to Mauge-Lewis. They have been used to manufacture many commercial and industrial products, such as stain-resistant fabrics and nonstick cookware.

“Even at low concentrations [in rodents], these chemicals can be detrimental in regard to kidney and testicular cancer, developmental defects, low birth weight, immune disorders, and thyroid disruptions,” he noted. Such findings come from broader NIEHS efforts to study the effects of PFAS.

In recent years, alternative versions of AFFFs have been developed, with the goal of helping people avoid potential health issues. For example, some of the foams contain PFAS with shortened carbon-fluorine chains to reduce how long the substances remain in the environment.

Liver toxicity

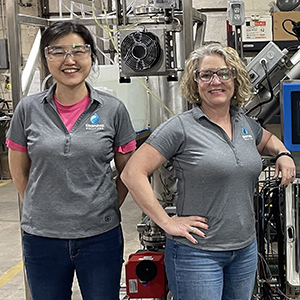

Fenton’s lab recently tested 10 of those AFFFs, building on collaborations with scientists at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and in academia (see sidebar). Mauge-Lewis studied their effects in a liver cell model.

Firefighting training is one of the main ways that AFFFs enter the environment.

Firefighting training is one of the main ways that AFFFs enter the environment.“We chose the liver because most PFAS tested in rodents affect it in a significant way,” said Fenton. “Also, we have a lot of experts in NTP with liver experience. We have both rat and human liver models. It’s really nice when you can compare across species and have greater confidence in your outcomes,” she added.

High concentrations of AFFFs killed most of the cells in the researchers’ liver model. But could substances other than PFAS be causing that cell death?

Mauge-Lewis tested a PFAS-only mixture and found that high concentrations resulted in almost identical damage to liver cells, suggesting that the toxicity came from PFAS rather than other chemicals or detergents.

Going forward, Fenton, Mauge-Lewis, and their collaborators will study how lower doses of AFFFs may affect key biological processes underlying other PFAS-associated health concerns, such as fatty liver disease.

(Jesse Saffron, J.D., is a technical writer-editor in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)