The National Toxicology Program (NTP) Board of Scientific Counselors (BSC) met Feb. 21 to discuss the critical issues of making toxicology testing more human relevant, as well as micro- and nanoplastics in our environment, among other topics.

“NTP’s key value is our ability to take on complex problems requiring prolonged focus,” said NTP Associate Director Brian Berridge, D.V.M., Ph.D., as he reflected on previous BSC input. “These are the things that nobody else can, or will, do and [this key value] is a great guide to the kinds of things we pick to focus on.”

“Part of NTP’s mission is to build confidence in new approaches,” said Berridge. “We are moving toxicology into a much more predictive science.” (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

“Part of NTP’s mission is to build confidence in new approaches,” said Berridge. “We are moving toxicology into a much more predictive science.” (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Because of the snowy weather in North Carolina, the board’s chairman, David Eaton, Ph.D., from the University of Washington, joined the other board members in an online-only meeting.

Organs-on-a-chip for human toxicity insight

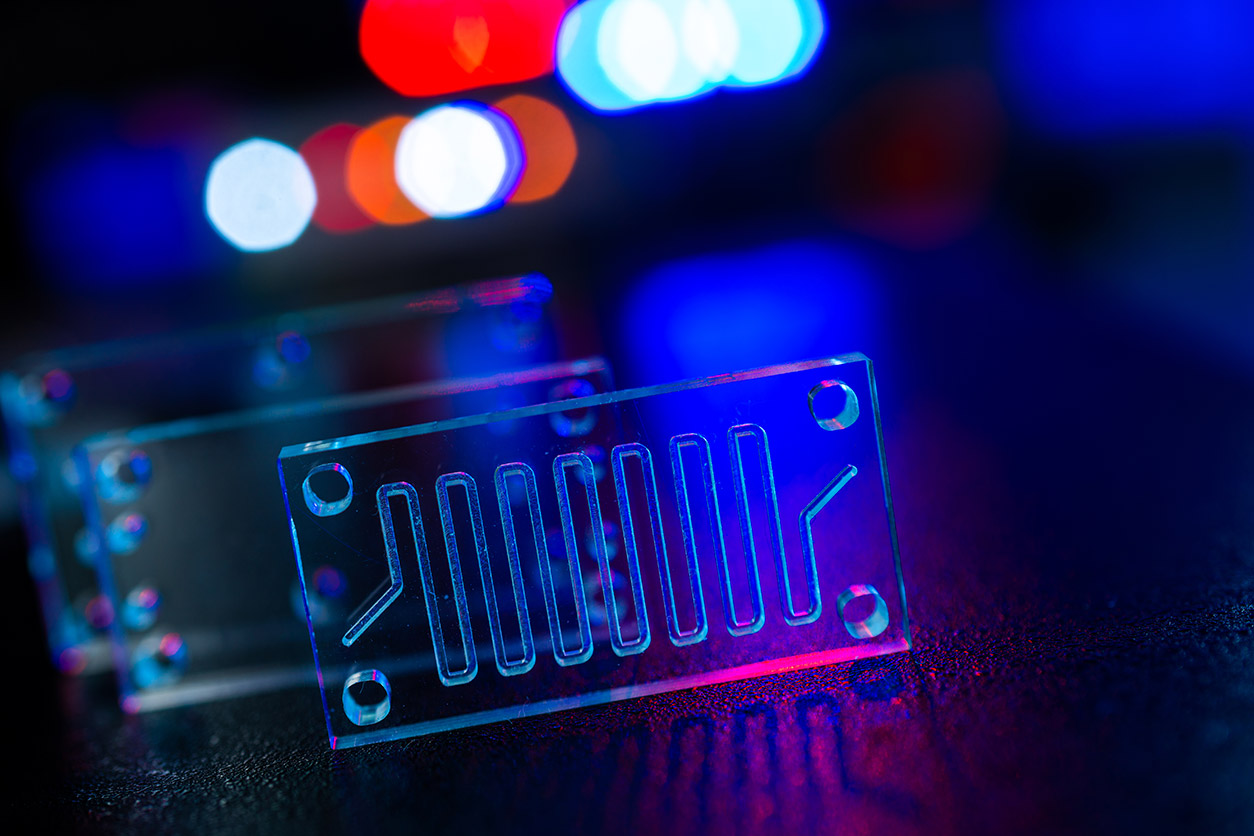

Berridge challenged the board to discuss developing novel approaches to some of the issues NTP grapples with, such as a reliance on animal testing. One example is known as a microphysiological system (MPS). These systems use multicellular organs-on-chips or 3D organs engineered from human cells to model how the human body responds when exposed to a potentially harmful chemical.

Organ-on-chip systems are one alternative to animal models. Populated by human cells, the systems model how different cell types or organs can interact in the human body.

Organ-on-chip systems are one alternative to animal models. Populated by human cells, the systems model how different cell types or organs can interact in the human body.To protect public health, animal studies have been effective at identifying chemicals that may cause human harm, but that protection has come at a significant price. Many researchers are reluctant to use animals in ways that intentionally cause harm. They also face the challenge of extrapolating effects in animals to potential effects in people.

“Most global communities frown on experimenting on people,” Berridge explained. “Could we leverage advances in modeling technology if we asked slightly different questions, while still protecting human health?”

MPSs allow researchers to answer questions in more human-like conditions.

- Does this chemical have activity in a human cell or tissue?

- What human cell or tissue type is most susceptible?

- At what exposure level do biological changes happen in human cells?

“NTP is really excited about this new technology, as it allows a fundamental shift in the way we think about toxicology testing,” Berridge said. “We’re moving from animal to human, from looking for a static effect to evaluating activity in a more dynamic way, and from a population focus to precision for individuals. It’s a way to reinvent how we traditionally do toxicology.”

The board was enthusiastic about the new approach and discussions touched on how a technology like this could supplement animal studies for comparison and interpretation of existing data.

BSC Chair Eaton, on screen, kept the meeting running smoothly despite a few technical glitches during the webcast. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

BSC Chair Eaton, on screen, kept the meeting running smoothly despite a few technical glitches during the webcast. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Other comments pointed to MPSs as a way to model the genetic differences seen between people, and how individual differences can affect a person’s response to a chemical exposure.

Microplastics — an emerging exposure challenge

On the topic of micro- and nanoplastics, the board heard from Anil Patri, Ph.D., director of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Nanotechnology Core Facility at the National Center for Toxicological Research. “Plastic waste is a global challenge,” he said. “We are producing more than 300 million tons of plastic every year, and only 10-15% of that is recycled. Most plastics end up in lakes or rivers.”

Patri explained that a single piece of large plastic can break down into millions of pieces of micro- or nanoplastics. Humans can be exposed through inhalation, skin contact, or ingestion. For example, microplastics have been found in honey, beer, poultry, seafood, salt, and sugar. Although there is yet no scientific evidence of human harm from these exposures, studies in zebrafish have shown that the particles can be taken up by tissues (see related story).

“This problem presents potential [opportunities for] collaboration between government agencies,” said Patri. “Currently, NTP and the FDA are working with groups that collect samples from various sources of potential human exposure and using existing knowledge with nanomaterial characterization to develop novel methods that are applicable to mixtures.”

Goncalo Gamboa da Costa, Ph.D., the FDA liaison to NTP, agreed that collaboration is key. “Different agencies have different questions and interests,” he said. “One point common to all is the need to understand what is out there. The issue of microplastics is a prime example of what NTP should be taking on as a collaborative entity.”

da Costa, left, spoke with Berridge, center, and NIEHS and NTP Director Rick Woychik, Ph.D., on NTP’s future plans. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

da Costa, left, spoke with Berridge, center, and NIEHS and NTP Director Rick Woychik, Ph.D., on NTP’s future plans. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)To close out the meeting, board members heard from two more scientists. Brandy Beverly, Ph.D., updated the group on recent NTP reports on traffic-related air pollution and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Researchers will build on its results with efforts to identify biomarkers that might clarify how exposures affect these disorders.

Chad Blystone, Ph.D., used the example of NTP studies of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, to foster discussion of how the program might better communicate study results to the public (see sidebar.)

“We’re using [traffic-related air pollution] as an example of how to address a contemporary issue in toxicology,” Beverly said. “We wanted to spark a question as to how to investigate this and look at other environmental exposures in the context of disease.” (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

“We’re using [traffic-related air pollution] as an example of how to address a contemporary issue in toxicology,” Beverly said. “We wanted to spark a question as to how to investigate this and look at other environmental exposures in the context of disease.” (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)(Sheena Scruggs, Ph.D., is digital outreach coordinator in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)