More than 90 researchers gathered in Washington, D.C., on April 29-30 for the Converging on Cancer workshop, to assess interactions between environmental exposures and cancer, and to identify the best areas to focus research. Organized by scientists from the National Toxicology Program (NTP); the University of California, Berkeley (UCB); and others, the meeting drew hundreds more attendees from around the world who joined via webcast.

Lead organizers for NTP were toxicologist Cynthia Rider, Ph.D., and Nicole Kleinstreuer, Ph.D., deputy director of the NTP Interagency Center for the Evaluation of Alternative Toxicological Methods.

Co-organizers Rider and Kleinstreuer took the lead for NTP. (Photo courtesy of Cynthia Rider)

Co-organizers Rider and Kleinstreuer took the lead for NTP. (Photo courtesy of Cynthia Rider)Cancer — complex, multiple diseases

According to the National Cancer Institute, cancer is a leading cause of mortality worldwide, leading to 609,640 estimated deaths in the United States in 2018. Cancer is not one disease, but a complex set of related diseases with many different causes. Environmental factors ranging from cigarette smoke to arsenic and certain pesticides are associated with cancer development and progression.

“NIEHS and NTP have a long history of evaluating the carcinogenic potential of environmental chemicals, including mixtures of chemicals,” said NIEHS and NTP Director Linda Birnbaum, Ph.D. “Currently, there are a number of complementary efforts underway to modernize our approach to understanding environmental chemical contributions to human cancer incidence.”

New vision for carcinogenicity testing

One such modernization was described by NTP Associate Director Brian Berridge, D.V.M., Ph.D., who shared a new focus at NTP called health effect innovation, which includes carcinogenicity testing.

By supporting a higher throughput approach to identifying environmental agents that might be carcinogenic, he explained, NTP hopes to gain a better understanding of environmental contributors to cancers that are either common or particularly lethal.

“Our progress in identifying agents that contribute to cancer risks will depend on our ability to model the transition from normal and adaptive biology to a disease state likely to lead to cancer development,” Berridge said. “We’ll also need to build confidence in the accuracy and relevance of novel testing systems and define an appropriate decision-making process.”

Defining hallmarks and key characteristics

Smith defined terms during his presentation on the workshop’s first day. (Photo courtesy of Nicole Kleinstreuer)

Smith defined terms during his presentation on the workshop’s first day. (Photo courtesy of Nicole Kleinstreuer)By defining terms, workshop speakers helped refine research questions. Dean Felsher, M.D., Ph.D., from Stanford University, described cellular characteristics, or hallmarks, of cancer.

“The idea is to formulate and organize principles for what kinds of biological processes need to be perturbed in order to have a cancer,” Felsher said. Cancer hallmarks include cellular activities such as resisting cell death, activating metastasis, and evading immune destruction.

Key characteristics are the action of a substance, such as altering a DNA repair process, or stimulating chronic inflammation. “A cancer hallmark is the biology of the cancer cell, while a key characteristic is what makes [that] biology happen,” explained Martyn Smith, Ph.D., from UCB.

“Using this knowledge, can we predict that a chemical might possess multiple key characteristics and prioritize it for further evaluation as a possible or probable human carcinogen?” he asked.

What about mixtures?

Scientists now question the assumption that chemicals act independently — an assumption that underlies toxicological studies and regulatory approaches. Yet we are exposed to complex mixtures, from sources as varied as air pollution and personal care products. The study of such mixtures is a major focus area in the NIEHS 2018-2023 Strategic Plan.

Danielle Carlin, Ph.D., from the NIEHS Hazardous Substances Research Branch, asked a question while Weihsueh Chiu, Ph.D., right, from Texas A&M and a member of the NTP Board of Scientific Counselors, took notes. (Photo courtesy of Amy Wang)

Danielle Carlin, Ph.D., from the NIEHS Hazardous Substances Research Branch, asked a question while Weihsueh Chiu, Ph.D., right, from Texas A&M and a member of the NTP Board of Scientific Counselors, took notes. (Photo courtesy of Amy Wang)Rider raised big picture questions to help the group form hypotheses for study. “Should we be addressing the joint action of co-carcinogens below their individual cancer thresholds?” she asked. “Or focusing on chemicals that are not complete carcinogens but target pathways that lead to cancer and could potentially contribute to cancer development jointly?”

Attendees addressed these and other questions in focus groups on mixtures, hazard and risk evaluation, and assays and technologies.

Kleinstreuer spoke for the assays and technologies group. “We should look at both the interaction between multiple carcinogens that act on different biological pathways, as well as noncarcinogens that might be promoting cancer,” she said. “We should also focus our energies on chemicals with a high public health impact, like [contaminants in] ground water.”

(Sheena Scruggs, Ph.D., is the Digital Outreach Coordinator in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)

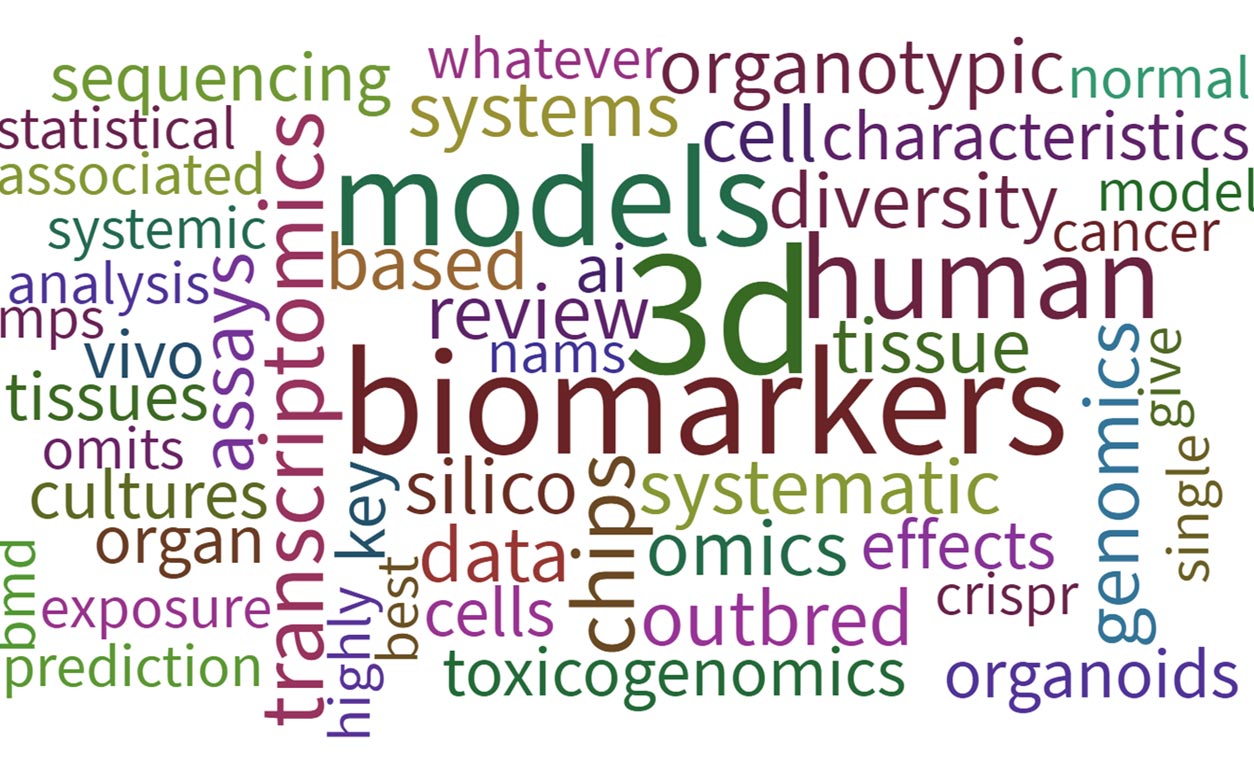

Participant responses to the question, “What technology holds the most promise for modern cancer assessment?” are represented in this word cloud. Polling was conducted with the Poll Everywhere web-based application. (Image courtesy of Cynthia Rider)