Telomeres, the repetitive DNA sequences that protect the ends of chromosomes from fraying like the caps on a shoelace, are more complicated than previously thought. They encode two small proteins that appear to play important roles in cancer and aging, according to a discovery by Jack Griffith, Ph.D., of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine.

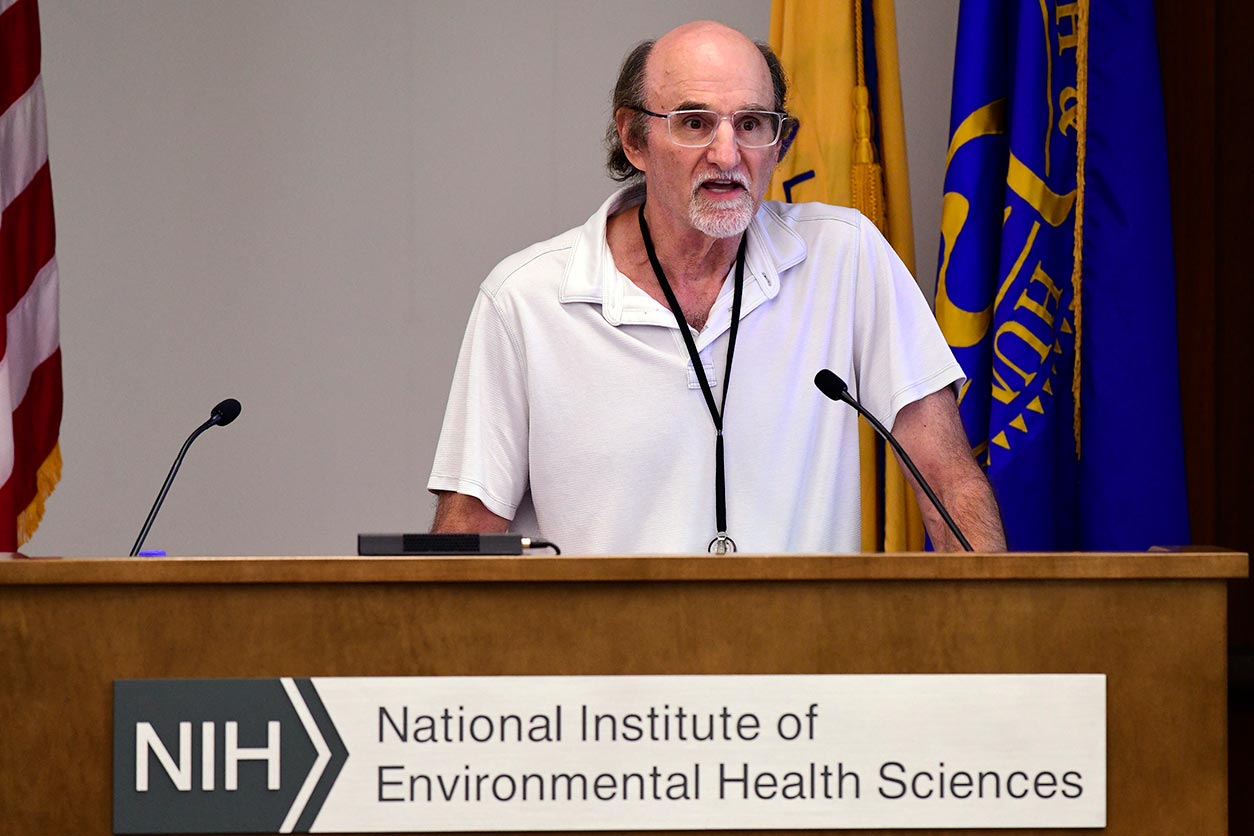

Griffith is a pioneer in electron microscopy, a sophisticated technique for capturing high-resolution images of biological specimens. His scientific snapshots have graced the covers of countless academic journals and textbooks. Griffith shared his research detailing how DNA and proteins interact during the second annual Sam Wilson Memorial Lecture August 2.

“Sam was a very dear friend,” said Griffith, explaining how they had worked together to bring the first cryogenic electron microscopy machines to Research Triangle Park. “I think if he was still with us, he would have been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences. He was very highly regarded, and so we miss him.”

There in spirit

NIEHS launched the Sam Wilson Memorial Lecture Series in 2023, two years after his death. Wilson was deputy director of NIEHS and the National Toxicology Program (NTP) from 1996 to 2007 and served as acting director from 2007 to 2009. Over the course of his career, he made seminal contributions to the study of genomic maintenance and DNA repair.

“Many of us adored Sam and looked to him for guidance,” said Bill Copeland, Ph.D., head of the NIEHS Genome Integrity and Structural Biology Laboratory. “The speakers we choose for this event emulate Sam’s spirit and quality of research.”

As Copeland explained, Griffith is known for his achievement both inside and outside of the laboratory. He grew up in Alaska and learned how to fly bush planes before most people knew how to drive. He likes to rebuild old cars, particularly Jaguars and Ferraris. He and his wife, the pianist Karen Allred, D.M.A., enjoy riding horses and raising their cats and dogs.

Griffith’s efforts to enable photography through the lens of the electron microscope garnered the 2021 Photographic Society of America’s Progress Award, putting him in the ranks of previous winners Walt Disney and Ansel Adams.

“He is considered the world’s guru on visualizing DNA-protein interactions,” said Copeland.

The tale of telomeres

Even though telomeres make up a small fraction of our DNA — less than 1/3,000th of the entire sequence — they play a big role in keeping us healthy. They keep track of how many times a cell has divided, help prevent cells from turning cancerous, and respond to damage caused by toxic substances. Griffith’s visual displays have provided critical insights into the function of these tiny structures.

For example, his microscopy work revealed that telomeres create loops by folding back on themselves, protecting the ends of chromosomes and keeping them from fusing together.

Recently, his research team showed that the genetic information contained within telomeres — the sequence TTAGGG repeated over and over again — serves another function. Taghreed Al-Turki, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Griffith’s lab, discovered that telomeres actually encode two very unusual proteins called VR (valine-arginine) and GL (glycine-leucine) that signal dysfunction. Both proteins form long filaments that can build up in cells and organs like the amyloid deposits seen in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

Griffith said that as we age, our telomeres shorten, which could trigger an increase in the levels of VR and GL in our cells.

“This could be a link between DNA damage and the formation of amyloid plaques in the brain or between aging and these diseases,” he said.

Some environmental chemicals might alter telomeres or cause telomere dysfunction, according to Griffith. In particular, he named chemicals including BRACO-19; 2,4-D, an herbicide; and Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), a plasticizer.

Griffith’s laboratory recently showed that exposing cells to BRACO-19 resulted in the dramatic accumulation of VR, suggesting that the chemical can have a big effect. But he said more experiments are needed to gain a clearer picture of what telomeres may be telling us about genomic and environmental toxicology.

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)