On August 26, Bevin Blake, a predoctoral researcher in the National Toxicology Program (NTP) Reproductive Endocrinology Group, spoke about a controversial group of man-made chemicals.

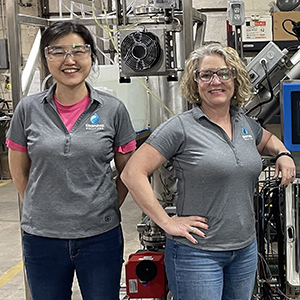

Blake, standing, explained some of the research methods used by scientists studying PFAS. (Photo courtesy of Jesse Saffron)

Blake, standing, explained some of the research methods used by scientists studying PFAS. (Photo courtesy of Jesse Saffron)She discussed per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) with local graduate students, early-career scientists, and citizens. A restaurant in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, hosted the event as part of a unique monthly series aimed at communicating science to a broad audience.

Today, more than 4,700 PFAS exist. They are found in many consumer and industrial products, such as food packaging, stain- and water-resistant fabrics, and firefighting foam.

Buyer beware

Unfortunately, explained Blake, some of the chemicals may increase risk for cancer, low birth weight, immune system deficiency, and elevated cholesterol levels.

Researchers are concerned because PFAS can stay in humans and the environment for many years. “They are considered forever chemicals because once they get into the environment, they essentially never go away,” she said. “This sets them apart from other environmental contaminants because most others will eventually break down.”

Blake pointed to research showing that PFAS, including perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), are in the blood of almost all Americans. “In fact, we detect these chemicals in the blood of polar bears, so that’s pretty far from their source,” she added.

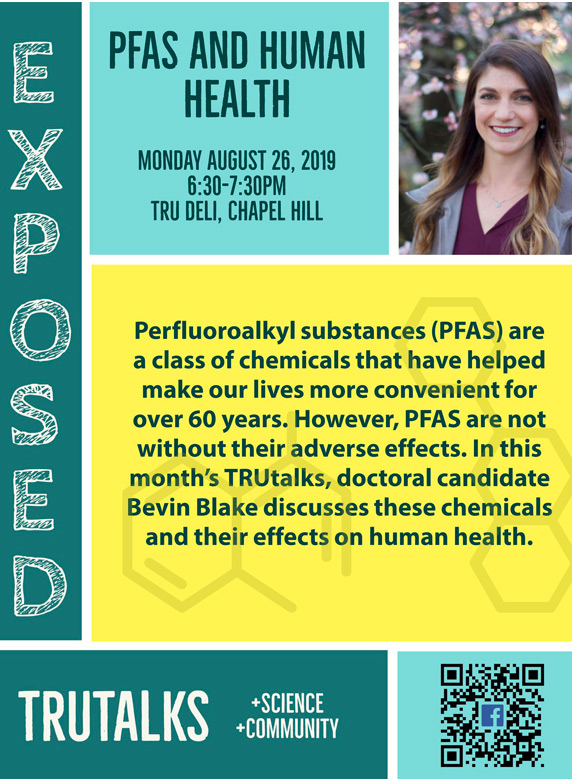

On social media, an e-flier advertised Blake’s talk. (Photo courtesy of @TruSciTalks, Twitter)

On social media, an e-flier advertised Blake’s talk. (Photo courtesy of @TruSciTalks, Twitter)Many U.S. companies have phased out PFOS and PFOA in recent years, but they persist in the environment — and many similar substitute chemicals are being created and made available for commercial use.

“We know absolutely nothing about health effects of replacement PFAS,” Blake said, likening the problem to a game of Whack-a-Mole. But policymakers, scientists, and stakeholders have made the chemicals a research priority.

Scientists respond

One example Blake shared is the North Carolina PFAS Testing Network, a research partnership whose participants include some NIEHS grantees. They measure the chemicals’ levels in water and air samples in an effort to inform state legislators and the public about potential contamination.

She also discussed research by grantee Scott Belcher, Ph.D., at North Carolina State University. His team studies how PFAS exposures in animals such as striped bass and alligators may shed light on the potential for risks to human health.

“There are fantastic [researchers] in his lab who are out there in the field sampling wildlife and giving us a better understanding of the environmental consequences of PFAS,” Blake added.

Earlier in August, Blake presented a poster about her PFAS research at a meeting of the North American Division of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Earlier in August, Blake presented a poster about her PFAS research at a meeting of the North American Division of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)At the national level, she said, NTP scientists and NIEHS-funded researchers(https://tools.niehs.nih.gov/pfas/) use a variety of methods to expand knowledge of these complex chemicals. Their groundbreaking work is receiving major public attention. But Blake said much remains to be done.

Raising awareness

“This [problem] has to do with the point in life at which you are exposed, various socioeconomic factors, genetic variation, and issues of environmental justice,” she said. “It turns out that people most affected are often ones at the lowest end of the socioeconomic spectrum.”

Blake suggested that consumers can spur positive change by being more mindful of products they purchase. “Think about these bigger-picture questions: What’s essential? What’s necessary? And what can we live without?”

(Jesse Saffron, J.D., is a technical writer-editor in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)