Environmental factors may be more closely tied to chronic disease development than genetics, according to Alison Motsinger-Reif, Ph.D., who co-leads the Personalized Environment and Genes Study (PEGS).

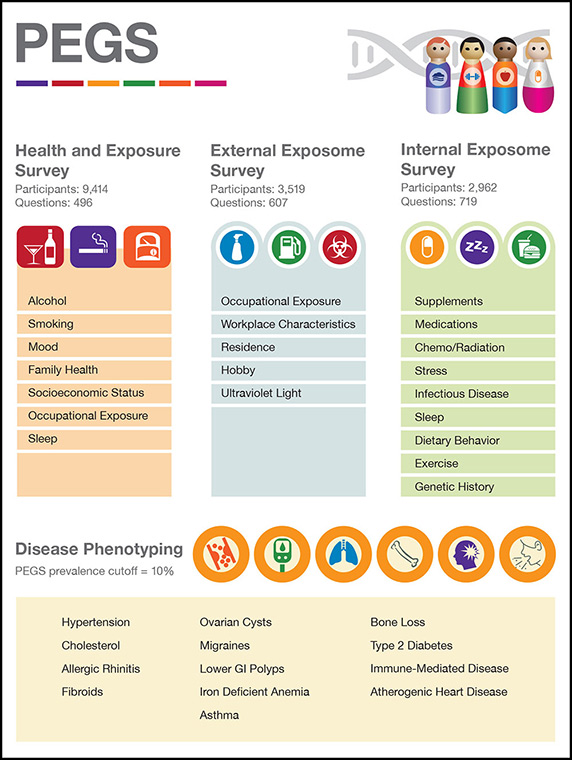

This ongoing study, begun by NIEHS scientists in 2002, collects extensive genetic and environmental data as well as self-reported disease information from nearly 20,000 participants. The team’s most recent statistical analysis assessed nearly 2,000 measures of health — including diet, lifestyle, occupational or home exposures, geographical distance to sources of pollution, and more.

“I'm hoping this knowledge could one day help clinicians decide who to screen for what diseases, which questions to ask, and how to tailor all of that information into more holistic care,” Motsinger-Reif said.

Motsinger-Reif presented the findings as part of a Center for Precision Health Research lecture held in-person and online by the National Human Genome Research Institute, Feb. 27.

Environment influences type 2 diabetes risk

Motsinger-Reif’s research team set out to determine whether participants’ genetic makeup, environmental exposures, or social environment best predicts development of specific health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cholesterol, and high blood pressure.

The researchers combined several measures known to influence each condition to arrive at a representative overall score, or “poly” score, for genetics, for exposures, and for social factors.

- Polygenic score: The overall genetic risk score for developing a condition that was calculated using 3,000 genetic traits.

- Polyexposure score: The combined environmental risk score calculated using exposures that can be modified or addressed through targeted interventions. Exposures include occupational hazards, such as chemical exposure or ergonomic risks, hobbies or lifestyle choices, and stress from work or social environments.

- Polysocial score: The overall social risk score includes factors such as socioeconomic status and housing, which are more difficult to change at the individual level.

The research team found the environmental risk score — the polyexposure score — served as the best predictor of disease development.

“In every case, the polygenic score has much lower performance than either the polyexposure or the polysocial score, and there’s really not a big difference between the polysocial and the polyexposure score,” Motsinger-Reif explained.

She added that when looking at genetics alone or social factors alone, the environmental risk score always added significant value in terms of predicting disease development.

Of all the diseases evaluated, the investigators found the environmental and social risk scores best predicted the development of type 2 diabetes.

More clues about the environment-health connection

PEGS researchers also recently identified potential links between study participants’ physical and social environments and cardiovascular disease using what’s called an exposome-wide association study. The exposome is the integrated compilation of physical, chemical, biological, and social influences and their impact on biology and health.

Researchers identified links between acrylic paint and primer exposure with stroke, and linked biohazardous materials with heart rhythm disturbances. Even a father’s level of education, a social influence, may raise the risk of stroke, heart attack, and coronary artery disease in his children.

They also found participants living nearer to a caged animal feeding operation, which produce meat, dairy, or eggs, had slightly to moderately higher risk of immune-mediated diseases. Further, living nearer to one of these facilities and having a specific genetic variant associated with autoimmune diseases more than doubled a person’s risk of developing immune-mediated conditions, including allergies and seasonal allergies.

On the horizon

“We often talk about the importance of genetic code, but this adds a whole different layer on that as we talk about lifestyle, environment, and biology,” said Josh Denny, M.D., who hosted the lecture and leads the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program.

Motsinger-Reif says that integrating environmental data holds the promise of uncovering environment-related biomarkers to improve diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of disease.

She is not alone in this belief. Researchers involved in nearly 50 collaborative studies have used PEGS data, which include participant responses to more than a thousand survey questions. PEGS investigators are now gathering longitudinal data by linking to electronic health records to follow changes in participants’ health over time. The goal is to inform clinical practice for more personalized medical care.

(Daniel M. Keller, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)

Explore NIEHS resources

To learn more about how a person’s lifestyle, physical environment, and social environment drive health and disease, check out the following NIEHS webpages and fact sheets.

Webpages: Biomarkers; Exposure Science; Nutrition, Health, and Your Environment.

Fact sheets: Endocrine Disruptors and Your Health; The Microbiome, the Environment, and Your Health; Occupational Health: Why the Environment Matters.