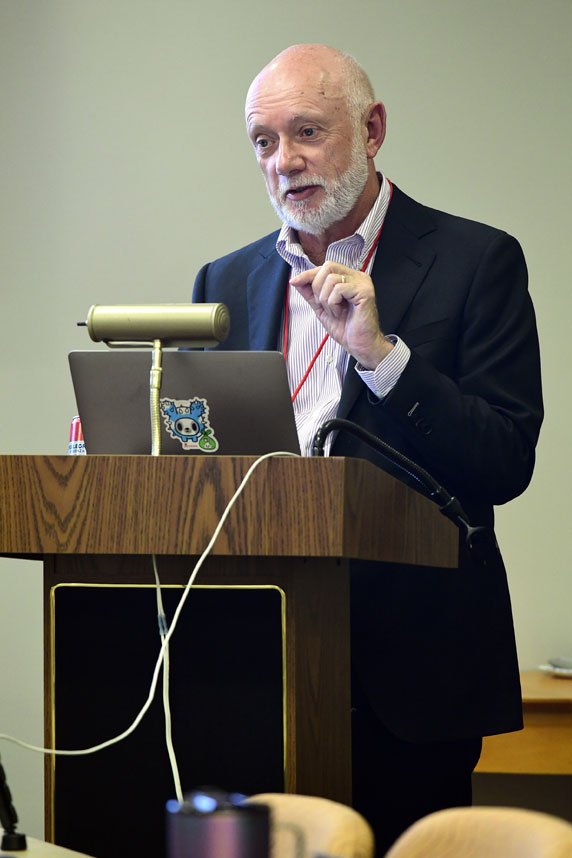

Researchers typically use three streams of evidence to assess whether a chemical may cause cancer or other adverse outcomes: epidemiological research (human populations), biological effects (animal models), and studies to identify underlying mechanisms driving disease. These days, mechanistic data is becoming increasingly important in identifying chemical hazards, as Martyn Smith, Ph.D., explained during his Jan. 14 Keystone Science Lecture.

But the growing number of chemicals — and the sheer volume of mechanistic data being generated about them — makes it challenging to prioritize which potential hazards to investigate.

“If you look for mechanistic studies for benzene, for example, you get about 7,000 papers,” said Smith, a distinguished emeritus professor of toxicology at the University of California, Berkeley.

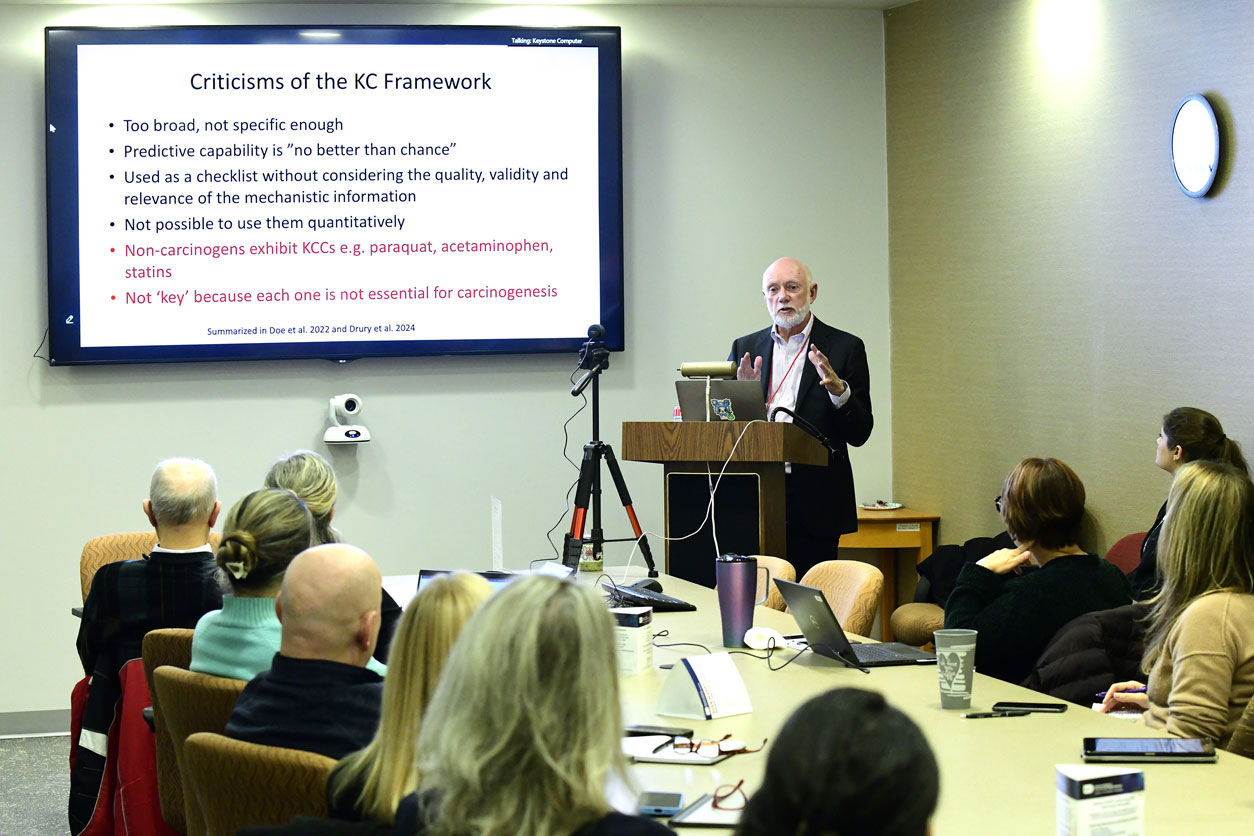

During his talk, Smith described a way to organize this data based on the properties of toxic chemicals. He and several colleagues first tested this concept by devising a list of 10 key characteristics of cancer-causing agents, like benzene. Smith has since helped to develop similar lists for endocrine-disrupting and metabolism-disrupting chemicals, as well as substances that can harm the heart, the liver, the reproductive system, and the immune system.

“He is very well-recognized for his innovative research, especially for his work on the key characteristics framework,” said Danielle Carlin, Ph.D., an NIEHS health scientist administrator who hosted the lecture.

The framework’s history

The framework emerged from meetings held in 2012 at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in Lyon, France. There, Smith led a subcommittee of working group members as they proposed and discussed the characteristics that were important for cancer development, including genomic instability, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Over the years, that list has been used by the National Toxicology Program Report on Carcinogens to help determine the likelihood that a chemical or other agent is a carcinogen.

Smith said the key characteristics of carcinogens should not be confused with the hallmarks of cancer.

“Hallmarks are properties of cancer cells and tumors,” said Smith. “Key characteristics are the chemical and biological properties of substances, and by substances we mean everything from viruses to chemicals to radiation.”

Umbrella and unique

In response to guidance from the National Academy of Sciences, teams of researchers also compiled key characteristics for other forms of toxicity. They quickly noticed that some characteristics were shared among various toxic substances, whereas others were very specific to certain toxicants.

Smith said that means there may be “umbrella” key characteristics for potentially hazardous chemicals that could be used in predictive toxicology.

“There are, however, characteristics that primarily target a specific organ and these ‘unique’ key characteristics could be especially important to predicting organ-specific toxicity,” said Smith. “This knowledge could help develop an overall battery of new approach methodologies.”

Further refinement

Smith proposed the use of AI and computational approaches to take the key characteristics framework to the next level. He and his team developed a database of all the methods used to evaluate the key characteristics of carcinogens. The resource will soon be made publicly accessible as a “living document” that will be continually updated.

Smith and team also created a web server called NR-TOXPRED that can be used to predict the activity of various potentially toxic chemicals. Through a large multisite collaboration, Smith and colleagues have used NR-TOXPRED and other computational tools provided by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the NIEHS Division of Translational Toxicology to screen 57,000 chemicals for potential toxicity. They have identified numerous environmental chemicals with high affinity for nuclear receptors, which control the biology of many cell types. Further validation of these findings is ongoing.

“I am very keen on this type of approach, which I think demonstrates that large-scale collaborations can be very productive,” said Smith.

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)