Scientists supported by the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (SRP) together with community and tribal members are using phytoremediation to remove PFAS from a contaminated site in northern Maine. Phytoremediation is a technique that takes advantage of plants’ ability to take up and accumulate hazardous substances from the environment.

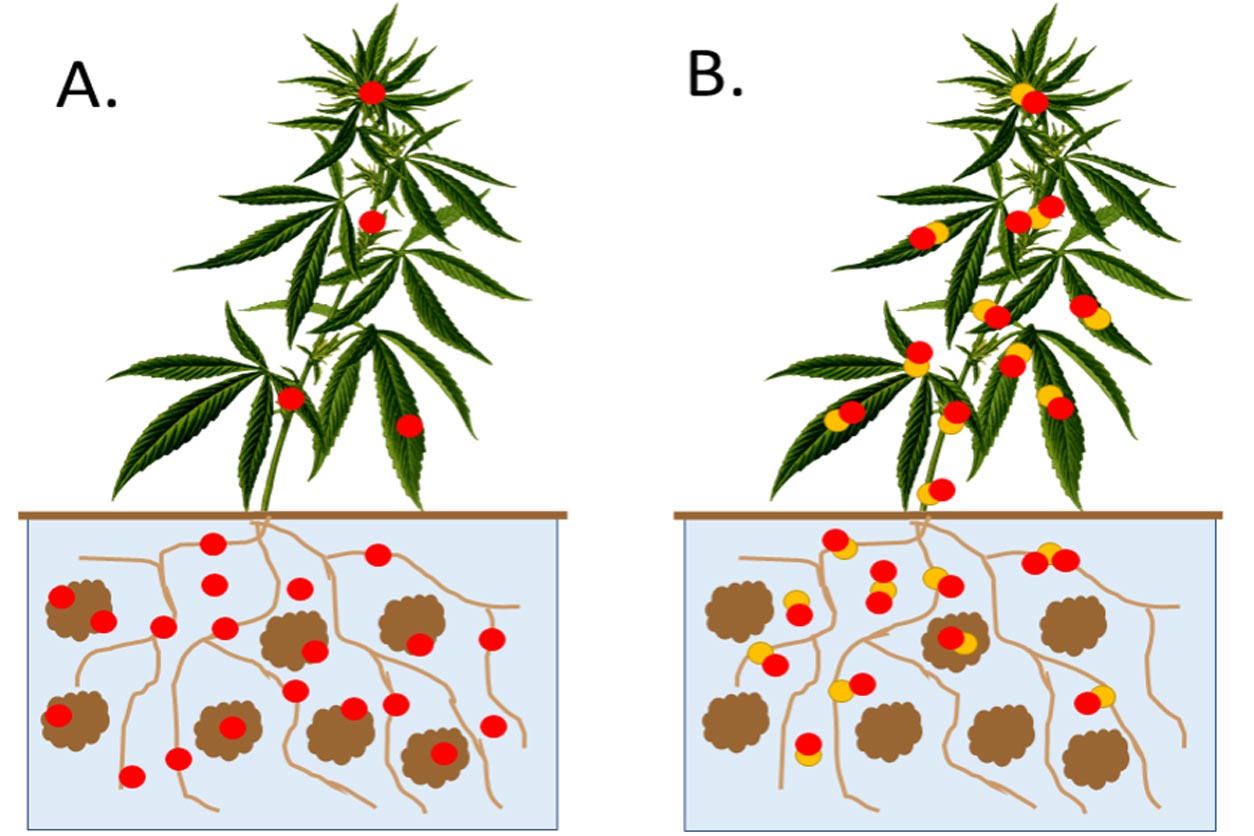

To boost the plants’ uptake of PFAS, the research team also plans to use nanoparticles made from silica, a chemical that is the main constituent of most rocks and minerals, and small carbon nanoparticles, called carbon dots.

“I hope that phytoremediation can become a feasible option for removing PFAS from soil,” said project researcher Sara Nason, Ph.D., of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES). “Current options are very limited overall, and phytoremediation on its own is not effective enough to produce the results many industries are seeking.”

The start of a collaborative project

In 2019, members of the Mi’kmaq Nation, an Indigenous tribe of about 1,500 people, and Upland Grassroots contacted CAES, a state government research organization. The goal was to kick-start a project using fiber hemp plants to remove PFAS from contaminated water and soil on land belonging to the Aroostook Band of the Mi’kmaq Nation. The land was formerly the site of Loring Air Force Base, which had for decades been a firefighting testing area. Firefighting foams usually contain PFAS because of the chemicals’ ability to suppress fire.

The collaborators chose fiber hemp because it grows quickly, takes up large amounts of water, and is usually not grazed by livestock. In addition, parts of the plant that are less suitable for PFAS storage, such as stems, may be used by tribal members to make products such as bricks and rope.

However, hemp plants are not able to remove all PFAS from soil and water because some of the molecules stay stuck in the soil. To address this challenge, CAES teamed up with researchers at Yale University and the University of Minnesota to study how nanomaterials can improve the ability of plants to absorb PFAS. SRP began to fund this research in 2021.

Nurturing community-based research

“I am proud that what started as a small pilot project working with Mi’kmaq community members and local organizations has grown into a large, multi-institution effort that still has ties to the community where the work started,” Nason said. “Having CAES staff funded by our SRP project has enabled us to be a stronger participant in remediation work with the tribe, while also pursuing new technologies to improve our current remediation options.”

While the nanomaterials are not yet ready for deployment in the field, work at the former Loring site has continued. CAES scientists work closely with Upland Grassroots and tribal leaders to develop plans for soil sample collection and hemp planting that allows the community to conduct most of the field research, while producing scientifically useful data.

“Listening to the needs of community researchers and designing projects around their interests and capabilities has been key to our success,” Nason said. “I hope that our work with Upland Grassroots and the Mi’kmaq Nation can be an example to other scientists doing community-based research.”

(Mali Velasco is a research and communication specialist for MDB Inc., a contractor for the NIEHS Division of Extramural Research and Training.)