Ciguatera poisoning is the most common non-bacterial seafood-borne illness in the world. More than 50,000 cases are reported annually, but scientists think that the true numbers may be much higher, because the symptoms — vomiting, diarrhea, tingling, muscle weakness and pain, and tactile sensitivity to cold — can be easily mistaken for other seafood illnesses.

During a Feb. 27 Keystone Science Lecture, Alison Robertson, Ph.D., described her team’s efforts to track the accumulation and movement of ciguatoxins — the source of ciguatera poisoning — in reef food webs across the world. There is no diagnostic test for ciguatoxins, which is why tracking their movement is so important.

“On a weekly basis, our team is contacted about poisoning outbreaks that are happening among people who have eaten seafood and ended up sick,” said Robertson, an associate professor at the University of South Alabama and senior marine scientist at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab. “We’ve seen an increase in the number of these reports at our lab, because not a lot is known about ciguatera, and people are desperate to find answers.”

Her team is interested in understanding how, when, and why the microscopic marine algae produce these potent neurotoxins, and how fish metabolize and respond to them when exposed. By tracing this complicated food web, they aim to develop better methods of predicting and monitoring ciguatoxin buildup in the environment and ultimately improve seafood safety.

“Dr. Robertson demonstrated that understanding the delicate balance of the aquatic ecosystem and marine life is crucial to answering some long-standing questions about ciguatera poisoning in humans around the globe that are pertinent for the development of prevention strategies,” said Anika Dzierlenga, Ph.D., a scientific program director in the Genes, Environment, and Health Branch and lecture host. “Her work is an excellent example of One Health research capturing the interrelatedness of environmental, animal, and human health.”

Uncovering the source

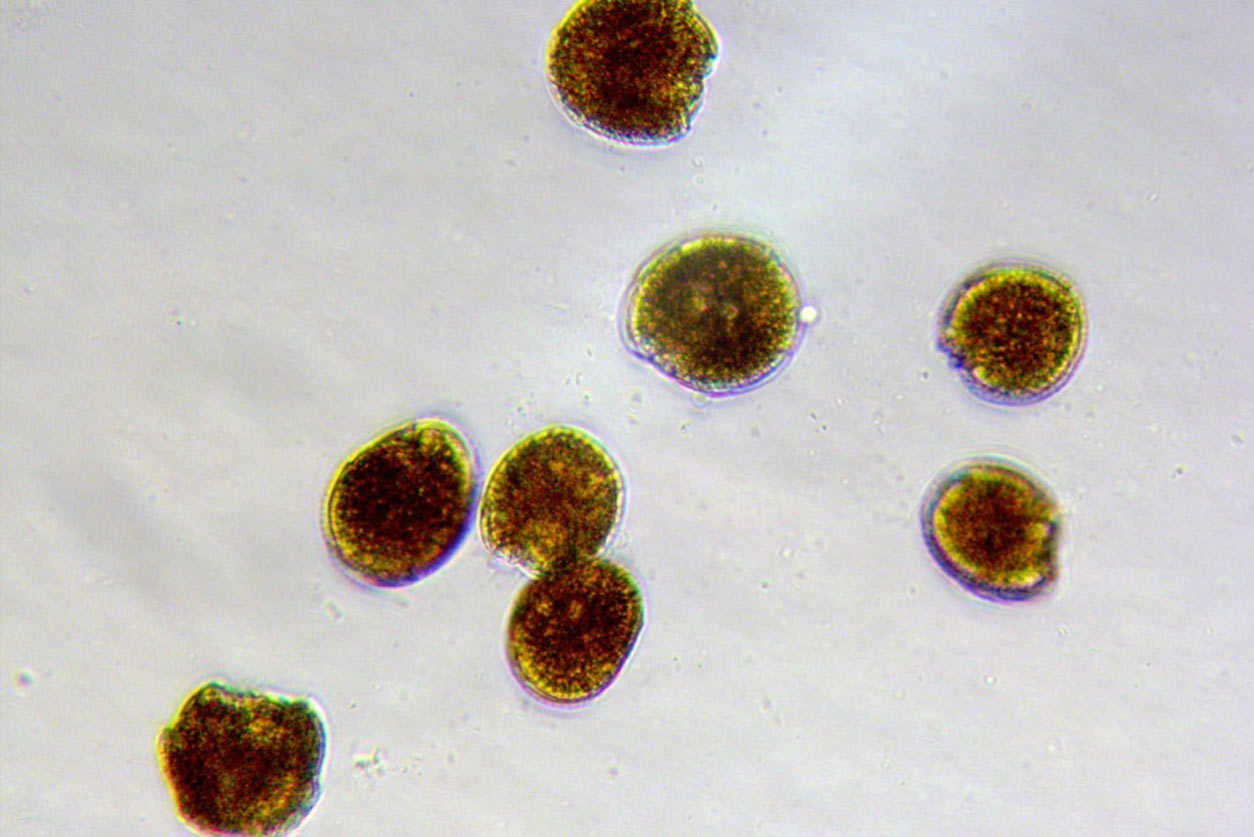

Robertson explained ciguatoxins first enter the food web when they are produced by some algae of the genera Gambierdiscus and Fukuyoa that live on degraded surfaces, as well as sea grasses and macroalgae in coral reefs. These microscopic algae are eaten by a wide variety of fish and marine invertebrates, which are, in turn, consumed by other reef predators, such as triggerfish, snappers, and grouper. If the fish have been feeding in an area where ciguatoxins are being produced locally, they also have the potential to bioaccumulate ciguatoxins and cause ciguatera if consumed by people.

In tracing ciguatoxin movement in the marine food web, Robertson and her collaborative team identified for the first time the specific type of algal ciguatoxin — a neurotoxin called Caribbean CTX-5 — that caused ciguatera in the Caribbean.

“We had identified Gambierdiscus silvae as the likely algal source species (along with a few others), but we had not yet worked out the toxin it was producing,” Robertson said. “Through strong partnerships and collaborations with the National Research Council and the Norwegian Veterinary Institute, we were finally able to uncover the toxins responsible, which makes tracing them through the environment a realistic goal, and something many in the field have been chasing for decades.”

Next steps

Given the lack of pre-market fish testing, diagnostic testing, and medication available to treat ciguatera poisoning, Robertson said she hopes her research will lead to more robust environmental monitoring of CTX-5 and other fish metabolites of the ciguatoxins to reduce ciguatera outbreaks in vulnerable communities.

“If money was no object, we would have teams in the water in all heavily impacted areas trying to do spatial surveys of the algae,” Robertson said. “Fishermen know quite a lot about areas that are causing illness, and they’re avoiding them. I would like to see teams that can integrate environmental sampling and monitoring with geospatial analysis and fisheries science to get to some kind of predictive capacity.”

(Ben Richardson, Ph.D., is a Presidential Management Fellow in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)