NIEHS-funded researchers have created a new framework designed to help scientists report back study findings about potential exposures to participants. The 12-point framework, developed by Katrina Korfmacher, Ph.D., and Julia Brody, Ph.D., aims to make report-back a routine part of research within the environmental health sciences.

“This is a timely project that aligns well with recent NIEHS efforts to advance report-back of gene-environment interactions to people participating in research studies,” said NIEHS Health Scientist Administrator Kimberly McAllister, Ph.D. “Their framework offers many valuable insights and guidelines needed to move this important area of environmental health research forward.”

Studies suggest there are a variety of benefits to reporting back personal data. In particular, participants who were informed of their study results displayed higher levels of scientific literacy, increased retention rates, and were more likely to take action against sources of harm (see sidebar).

Despite these benefits, report-back has not yet been widely adopted in the environmental health sciences. In proposing their framework, the authors hope to change this by providing a blueprint for institutionalizing appropriate participant report-back.

“Community-based research teams have laid a really strong foundation outlining how and why to report back,” said Korfmacher, a professor of environmental medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center. “But to scale that up across the environmental health sciences, we need funders, institutions, reviewers, and regulatory systems to set clear guidelines.”

12 steps to implementing report-back

Korfmacher and Brody offer a 12-point framework designed to encourage report-back within the wider environmental health sciences community. Their proposals are divided into three sections, each of which corresponds to a major need within the field.

Guidelines

- Set expectations for participant-centric design of report-back plans.

- Specify components of report-back plans by providing details about when, how, and with whom data will be shared.

- Clarify strategies to appropriately communicate uncertainties in research data so that people can make decisions based on their own values.

- Convene stakeholders to refine guidelines for specific types of research across different fields in the environmental health sciences.

- Include report-back plans in relevant funding opportunities offered by individual grant-making agencies.

- Disseminate report-back guidelines to affected stakeholders, such as researchers, review boards, and community partners.

Training

- Train research teams, reviewers, and review boards in how to report back study results in accordance with the guidelines.

- Train external stakeholders, such as community members, clinicians, or government partners, so they can support participants who wish to act on the data reported back to them.

Resources

- Provide appropriate financial resources to support report back in the form of grants, post-grant awards, or individual research supplements.

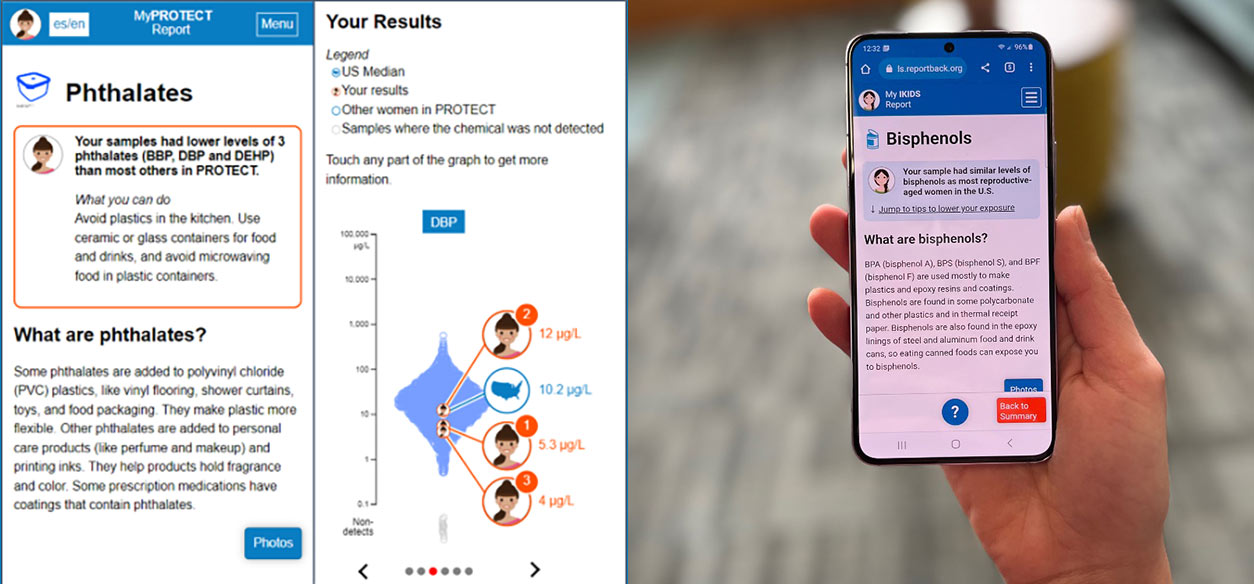

- Create cost-effective tools and shared report-back infrastructure, such as science-based content libraries, semi-automated reporting platforms, and digital applications.

- Develop resources to meet environmental health researchers’ needs, such as guidance for laboratory standards and legal issues.

- Focus on accessibility, equity, and action as basic principles to maximize report-back’s contribution to promoting environmental justice.

Future of community-engaged research

Taken together, these proposals offer a detailed road map for navigating the future of report-back in the environmental health sciences.

“Our framework highlights the importance of engaging with participants, community leaders, and public officials to develop meaningful report-back protocols,” said Brody, who leads the Silent Spring Institute. “We hope to guide scientists in using report-back as a core part of environmental health research.”

Silent Spring Institute researchers will lead a hands-on digital exposure report-back interface (DERBI) training, as well as a workshop with Korfmacher on operationalizing this framework at the upcoming NIEHS Partnerships for Environmental Public Health meeting Feb. 20-22. In addition, individuals interested in online training can register here.

(Ben Richardson, Ph.D., is a Presidential Management Fellow in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)