Pauli Murray was many things in life, but in all things, a trailblazer. A Black lawyer and activist for gender equality and civil rights, a published poet, and an episcopal priest, she was long overlooked by history. The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice in Durham, North Carolina (see sidebar), is now helping to tell and preserve her stories, noted center director Barbara Lau during a July 21 virtual lecture.

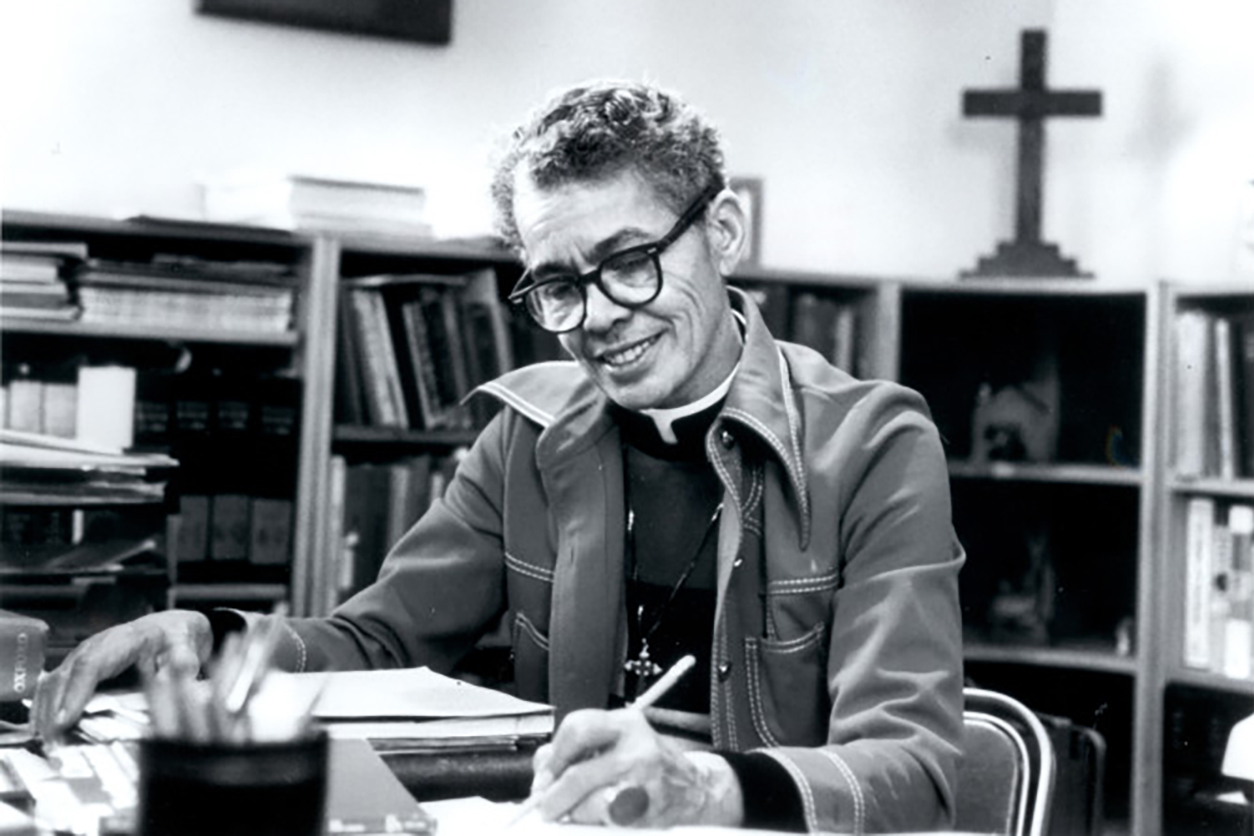

In 2012, the Episcopal Church named Pauli Murray a saint, acknowledging her as the first Black female priest. (Photo courtesy of Carolina Digital Library and Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

In 2012, the Episcopal Church named Pauli Murray a saint, acknowledging her as the first Black female priest. (Photo courtesy of Carolina Digital Library and Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)Lau’s presentation was sponsored by the NIEHS Office of Science Education and Diversity both as part of the institute's Diversity Speaker Series and in recognition of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion’s Special Emphasis Portfolio for Sexual and Gender Minorities.

“Murray was a visionary leader, yet many people don’t know about her legacy,” said Sharon Beard, head of the NIEHS Worker Training Program. “I am glad that Murray is being recognized in today’s talk because her life and contributions are truly inspiring.”

Pursuing social justice, equality

One of six children, Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland. When her parents died suddenly, Murray went to live near her maternal grandparents in Durham, North Carolina, where Murray was raised by an aunt.

When Murray reached college age, the historically Black Wilberforce College in Ohio offered her a full scholarship. Instead, she wanted to attend an integrated school, so Murray went to New York City to see Columbia University. At the time, however, women were not allowed to study at the university, so she visited the women’s school across the street, Barnard College.

Finding that the family did not have the resources to attend the college, she visited Hunter College, a state school in the city. When Murray realized that she didn’t have enough of an education to apply, she earned an additional high school degree before applying to Hunter College, where she graduated in 1933.

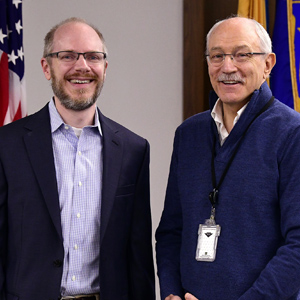

Barbara Lau is executive director of the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice. (Photo courtesy of Barbara Lau)

Barbara Lau is executive director of the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice. (Photo courtesy of Barbara Lau)During those years, Murray explored her interests and worked as an elevator operator, a teacher with the Works Progress Administration, and a waitress. She chose a gender-neutral name, Pauli, and met with doctors about gender confirmation treatments, including hormone therapy, but was refused treatment.

“I think it was also during this period that Pauli found they were attracted to women and began a process of discernment around gender identity and sexuality that was a part of the rest of their life,” said Lau. (A webpage developed by the Pauli Murray Center explains the use of they/them/their pronouns in the context of Murray’s history.) “They were very driven by these principles of social justice and human equality.”

Several years later, Murray returned to Durham at the request of her aunts, who felt like they needed more help at home.

Making an impact

Back home in North Carolina, Murray was eager to enroll in a new graduate program in sociology focused on race relations, which was housed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had just visited the university, extolling its virtues as a progressive institution. But UNC was not admitting Black students, even to its program on race relations.

Incensed, Murray wrote a letter to the president and sent a copy to his wife, Eleanor, asking how UNC could be considered progressive when it wouldn’t allow Black students into its graduate school program on race relations. The letter began a relationship between the First Lady and Murray consisting of more than 300 letters now memorialized in the 2016 book The Firebrand and the First Lady.

Eventually, Murray earned a scholarship to attend law school at Howard University, where they crafted a paper proposing a different argument to dismantle Plessy v. Ferguson, a case that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation. Years later, the NAACP used Murray’s argument to win the Brown v. Board of Education case that desegregated schools across the country, a fact Murray didn’t know until years later.

When Murray graduated at the top of their class, an accomplishment that usually allowed one to continue their education at Harvard Law School, Murray was prohibited from attending because of their gender, despite having a letter of recommendation from Franklin D. Roosevelt. They enrolled in what is now Berkeley Law to get their LLM degree.

Later, Murray went to New York to open their own law practice, and they would eventually write State Laws on Race and Color, which documented all such laws in every state.

“It really made a big difference to have this compilation,” said Lau. “Thurgood Marshall later referred to this as the Bible for civil rights litigators who, in many places, were looking for those cases that could eventually help to overturn Jim Crow laws or, as Murray later called them, Jane Crow laws.”

A person of firsts

Murray went on to become the very first Black person of any gender to graduate with a Doctor of Science of Law degree from Yale Law School in 1965. While there, they wrote a dissertation on policy and women's rights, mentoring young women such as Eleanor Holmes Norton, J.D., who now represents the District of Columbia in Congress, and Marian Wright Edelman, who founded the Children's Defense Fund.

Murray and her partner of 20 years, Irene Barlow, had been active Episcopalians who encouraged policy changes to allow women to become priests. When Barlow died, Murray turned her attention to faith and enrolled in divinity school, waiting four years before the church allowed women to become priests. Murray eventually became the first Black woman ordained.

“Pauli Murray might not have been a person of their day, but they are certainly a person of our day,” said Lau.

(Susan Cosier is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)