Fenton is an expert on how PFAS can affect reproduction and early-life development. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Fenton is an expert on how PFAS can affect reproduction and early-life development. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)Manmade substances known as forever chemicals were front and center during the 3rd National PFAS Meeting held June 15-17 in Wilmington, N.C. Scientists, community members, and policymakers shared research and, in some cases, emotional stories about per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

“We designed the meeting that way because the communities affected by PFAS really know what is going on,” said event organizer and moderator Suzanne Fenton, Ph.D., from the NIEHS Division of the National Toxicology Program. “Engaging them was a fabulous way to support the communities affected.”

Former NIEHS and National Toxicology Program Director Linda Birnbaum, Ph.D., spoke about the health effects of PFAS and the need for more research. She received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the nonprofit Clean Cape Fear.

EPA health advisories

The meeting made headlines when Radhika Fox, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Assistant Administrator for Water, announced new health advisories for drinking water standards for four PFAS: PFOA, PFOS, PFBS, and GenX.

Although health advisories are nonbinding, in the cases of PFOA and PFOS, “safe” levels were reduced to parts per trillion below detectable levels, meaning no amount is now considered safe.

Later this year, Fenton said, the EPA will propose draft PFOA and PFOS Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs). “Once the MCLs are finalized, those values will be regulatory,” she said. “So, essentially, these health advisories are a ‘Get Yourself Ready’ warning.”

Cape Fear contamination

“Students and scientists had opportunities to connect with people in the community, and seeing that was powerful,” said Hoppin, shown here at a 2018 NIEHS meeting at which she discussed the chemical GenX. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

“Students and scientists had opportunities to connect with people in the community, and seeing that was powerful,” said Hoppin, shown here at a 2018 NIEHS meeting at which she discussed the chemical GenX. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)Jane Hoppin, Sc.D., who directs the Center for Human Health and the Environment at North Carolina State University (NC State), served on the event organizing committee. She described PFAS contamination of the Cape Fear River and watershed — a major focus of the meeting.

In June 2017, the discharge of GenX and other PFAS directly into the Cape Fear River by a Chemours chemical plant became public knowledge when the Wilmington Star News broke the story of the widespread contamination. Wells miles away — upriver but downwind — had also been contaminated when PFAS emitted into the air fell back to earth in rainwater.

“People woke up to find out they’d been drinking Teflon for 40 years,” Hoppin said.

Cooperation — and painful stories

Hoppin, who also directs the GenX Exposure Study at NC State and is a member of the Center for Environmental and Health Effects of PFAS at the university, praised the comprehensiveness of the three-day event.

“The EPA health advisories are the headline, but the more profound thing for the meeting was how it really brought the community and scientists to the table,” Hoppin said.

She spoke of the emotional impact of hearing how these chemicals have affected people’s lives. Women choosing not to breastfeed because of the PFAS levels in their bodies. Maine dairy farmers whose fields are contaminated by PFAS that lead to contamination of milk. Firefighters who say they have been lied to about the health impacts of chemicals in firefighting foam — and breaking down about colleagues getting cancer in their early 30s.

“We also got to hear how grateful people are for what we’re doing,” Hoppin said. “Children sent drawings thanking us for studying PFAS. That's pretty adorable.”

“The EPA announcement was great,” she added, “but it doesn’t change the fact that all of these communities have been exposed without their knowledge. How can we help identify solutions for them?”

Listening, learning

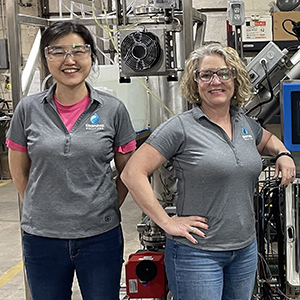

“Things are going to get done,” Markesino said. “You know the needle is moving.” (Photo courtesy of Beth Markesino)

“Things are going to get done,” Markesino said. “You know the needle is moving.” (Photo courtesy of Beth Markesino)Beth Markesino has a partial answer. She lives in Wilmington and is the founder of North Carolina Stop GENX In Our Water. “In 2017, I lost my son Samuel at 24 weeks of pregnancy, when he failed to develop critical organs,” she said. “Later, we learned about our water contamination. I started our Facebook group that day, which later became a 501(C)(3).”

The group shares information about PFAS in drinking water and sponsors a billboard campaign in the Wilmington area. They also help provide low income and minority residents with water filtration devices.

Markesino is from Michigan, where she worked on the Flint water crisis. “I've been to a few of these conferences,” she said. “You don't think somebody is listening, and then you go to an event like this, and they're listening and want to know your opinion. That means a lot to us.”

The event was funded in part by NIEHS and hosted at Cape Fear Community College by the Center for Environmental and Health Effects of PFAS.

(John Yewell is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)