At the NIEHS Autism Awareness Month seminar on April 11, speakers focused on gene-environment associations in autism and how tailoring learning environments for children with autism can improve their capacity to learn and communicate.

Hosted by Cindy Lawler, Ph.D., and Astrid Haugen, both from the NIEHS Genes, Environment, and Health Branch, the event featured presentations by institute grantee Heather Volk, Ph.D., from Johns Hopkins University, and John Constantino, M.D., from Washington University School of Medicine. Research by Volk and Constantino intersects in several ways, including that both scientists use twin or family studies to research gene-environment interactions involved in neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

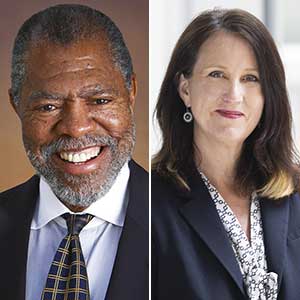

Lawler, left, is the lead NIEHS representative for extramural research related to autism. Haugen, right, coordinates activities and provides oversight for the institute’s Autism and Environment program. (Photos courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Lawler, left, is the lead NIEHS representative for extramural research related to autism. Haugen, right, coordinates activities and provides oversight for the institute’s Autism and Environment program. (Photos courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)“NIEHS supports research that investigates how environmental factors like air pollution, pesticides, or maternal nutrient levels may interact with genetic factors during development to increase or decrease risk of ASD,” said Haugen.

Heritability, diagnosis, intervention

Constantino first focused on metrics of heritability uncovered from studies involving children who are twins, where both or only one of the twins are autistic.

“If a child has autism and they have an identical twin, there’s a 90% chance their twin has autism as well,” he said. “If you take a pair of twins reared in the same environment and the same exposures but cut the genetic similarity of the twins in half, the likelihood of both being autistic plummets to 20%.”

Constantino noted that autism occurs uniformly across socioeconomic strata in the U.S. (Photo courtesy of John Constantino)

Constantino noted that autism occurs uniformly across socioeconomic strata in the U.S. (Photo courtesy of John Constantino)According to Constantino, 85% of autism is caused by population-attributable inherited risk, but the role that gene-environment interactions play in influencing the likelihood of a child having autism is not yet known.

“We often underestimate what the environmental influence is for a condition through twin studies like this [because] those environmental factors remain unmeasured,” he said. “Unless we measure them and study interaction with genetic factors, we can’t know causation.”

Constantino stressed the importance of early diagnosis and intervention. Unfortunately, he noted, there is a significant increase in care disparities among Black and African American populations. That could be due to a variety of issues, ranging from the effects of socioeconomic stress to the increased likelihood that polluting industries are in areas where most residents are minorities.

“There’s a very sad gene-environment correlation in our country,” he said. “If the color of your skin is black or brown, that is associated with cognitive impairments that disproportionately compound autism. There is evidence that this is due in large measure to a general lack of service access and delay in diagnosis. That delay occurs not because the families are not insured or parents weren’t concerned, but because of an average 42-month delay in establishing a diagnosis, and race-based disparities in access to intervention services after a diagnosis is made. There’s no excuse for this anymore. This is an environmental variable we have control over, and we must do something about it.”

There is good news, according to Constantino. He noted that children who received just five hours of focused intervention per week for nine weeks showed significant cognitive gains in a current pilot program that couples early diagnosis with definitive, autism-specific intervention.

“It would be great to prevent and treat core symptoms, but it’s very important to make this point that improvement in adaptive functioning — even if core symptoms don’t change — is very worth pursuing,” he said. “Improvements in communication, composure, and/or response to unexpected day-to-day life events can make or break quality of life of an individual with autism and can change the manner in which they adapt to their condition and express themselves.”

Environmental exposures and autism

Volk also focused on heritability and autism in families, with a special focus on the potential role of air pollution. Both Volk and Constantino noted that in families with an autistic child, the condition’s incidence increases with the number of children, but symptoms and severity vary significantly.

“ASD occurrence varies wildly throughout the world,” Volk said. “Due to the issue of competing risks, such as bigger challenges to survival, ASD often isn’t diagnosed.” (Photo courtesy of Heather Volk)

“ASD occurrence varies wildly throughout the world,” Volk said. “Due to the issue of competing risks, such as bigger challenges to survival, ASD often isn’t diagnosed.” (Photo courtesy of Heather Volk)“Clearly, something is happening broadly here when looking at the ASD phenotype,” Volk said. She added that genetic risks are likely compounded by environmental exposures, but researchers are not yet sure to what extent.

Constantino and Volk agreed that a limitation to the study of autism is that most genetic samples come from people of European ancestry, which likely also contributes to delays in diagnosis among non-White populations.

“If you want a polygenic risk score that works in all ancestral backgrounds, you have to test it in all ancestral backgrounds so that it represents all human diversity,” Constantino said. “And we haven’t done that yet.”

Environmental epidemiology suggests that there are many places where interventions can improve quality of life and level of functioning in people with ASD, according to Volk. Those include limiting exposures to chemicals in air pollution and pesticides, as well as limiting maternal exposures in utero, such as alcohol and tobacco. Maternal body mass index and gestational diabetes appear to be influential, but so too is “neighborhood deprivation,” meaning a lack of green space and proximity to industrial facilities where there may be greater exposure to fine particulate matter emissions.

“Air pollution has broad effects on the developing brain and neurodevelopment,” said Volk. “Numerous studies look at prenatal air pollution exposure and ASD. More recent papers note poor performance among ASD cases when there is exposure to environmental pollutants.”

Volk noted that the temporal nature of some exposures, such as to heavy metals, makes it difficult to measure the impact on autism risk. Potential avenues for future study include assessment of body burden of microplastics, flame retardants, and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

(Kelley Christensen is a contract writer and editor for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)