Effectively communicating research with non-scientific audiences is challenging, and it requires practice. For the past seven years, the NIEHS Office of Fellows’ Career Development (OFCD) has sponsored a competition that gives early-career researchers an opportunity to explain their science in plain language, in just three minutes.

This year’s event, held March 10, was titled “Big Picture, Small Talk: Environmental Health and Science for a General Audience,” and it included presentations by 10 NIEHS fellows. The three winners, listed below, will receive $1,500 for either travel to a scientific conference or professional development.

- Ayland Letsinger, Ph.D., Intramural Research Training Award (IRTA) postdoctoral fellow in the Neurobiology Laboratory, mentored by Jerry Yakel, Ph.D. Letsinger aims to find out why people like — or don’t like — physical activity.

- Ciro Amato, Ph.D., IRTA postdoctoral fellow in the Reproductive and Developmental Biology Laboratory, mentored by Humphrey Yao, Ph.D. Amato studies the biological mechanisms involved in a birth defect called hypospadias.

- Paige Bommarito, Ph.D., IRTA postdoctoral fellow in the Epidemiology Branch, mentored by Kelly Ferguson, Ph.D. Bommarito researches the causes and effects of fetal growth restriction.

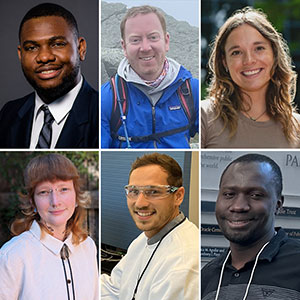

Your 2022 Big Picture, Small Talk winners, clockwise from top: Bommarito, Amato, and Letsinger. Each excelled in their three-minute presentations. (Photo courtesy of Tammy Collins / NIEHS)

Your 2022 Big Picture, Small Talk winners, clockwise from top: Bommarito, Amato, and Letsinger. Each excelled in their three-minute presentations. (Photo courtesy of Tammy Collins / NIEHS)“It is clear that it is becoming increasingly important to be able to communicate with the broader public so that they understand the importance of the scientific research we are doing and why we are doing it,” said OFCD Director Tammy Collins, Ph.D. “This annual challenge encourages NIEHS fellows to step outside of their everyday box and really think about their work in the broader picture of how it can benefit society, and how to articulate that to people.”

Get off the couch

Letsinger, the top vote-getter in the competition, studies why people like or dislike physical activity. He noted that there is a critical need to improve abysmally low levels of physical activity.

“My objective is to discover why an organism may choose to engage in physical activity by measuring sub-second fluctuations of neurotransmitters in the brains of mice during wheel running,” Letsinger explained.

“Once characterized, we may be able to increase physical activity levels by modulating the function of those neurotransmitters through nutritional or pharmaceutical interventions,” he added.

Focusing on a common birth defect

Amato researches a birth defect called hypospadias, which is a malformation of the penis where the urethra does not form at the tip but rather somewhere along the shaft. About 1% of boys are born with hypospadias.

“What’s really concerning is that the incidence has nearly doubled over the past 60 years,” he said. “We think this is largely due to environmental contaminants such as pesticides and plastics that are being ingested by the mom,” Amato noted.

“My research is focused on understanding how the normal penis develops so that we can make more and better hypotheses about what's causing hypospadias,” he said.

“So, what I’m doing now is looking at how cells in the penis are communicating, and I’m identifying novel factors that are potentially contributing to hypospadias in humans,” added Amato. “I'm planning to investigate how things like plastics and pesticides can disrupt normal communication between the different cell populations.”

Babies’ growth trajectories

Bommarito’s talk focused on her work to strengthen clinicians’ ability to identify fetal growth restriction. That is a birth outcome that increases the risk of health complications, including infant death.

“One of my goals is to use novel statistical methods to help us better distinguish the babies that truly have birth restriction from those that are perfectly healthy but just a little small,” she said.

“I have found that babies that have the smallest growth trajectories from mid through late pregnancy are at higher risk compared with other babies, regardless of their weights at the time of delivery,” noted Bommarito.

“This work will have broad impact on both research and clinical settings because our ability to understand and ultimately prevent the effects of growth restriction is only as good as our ability to diagnose it,” she added.

(Ernie Hood is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)