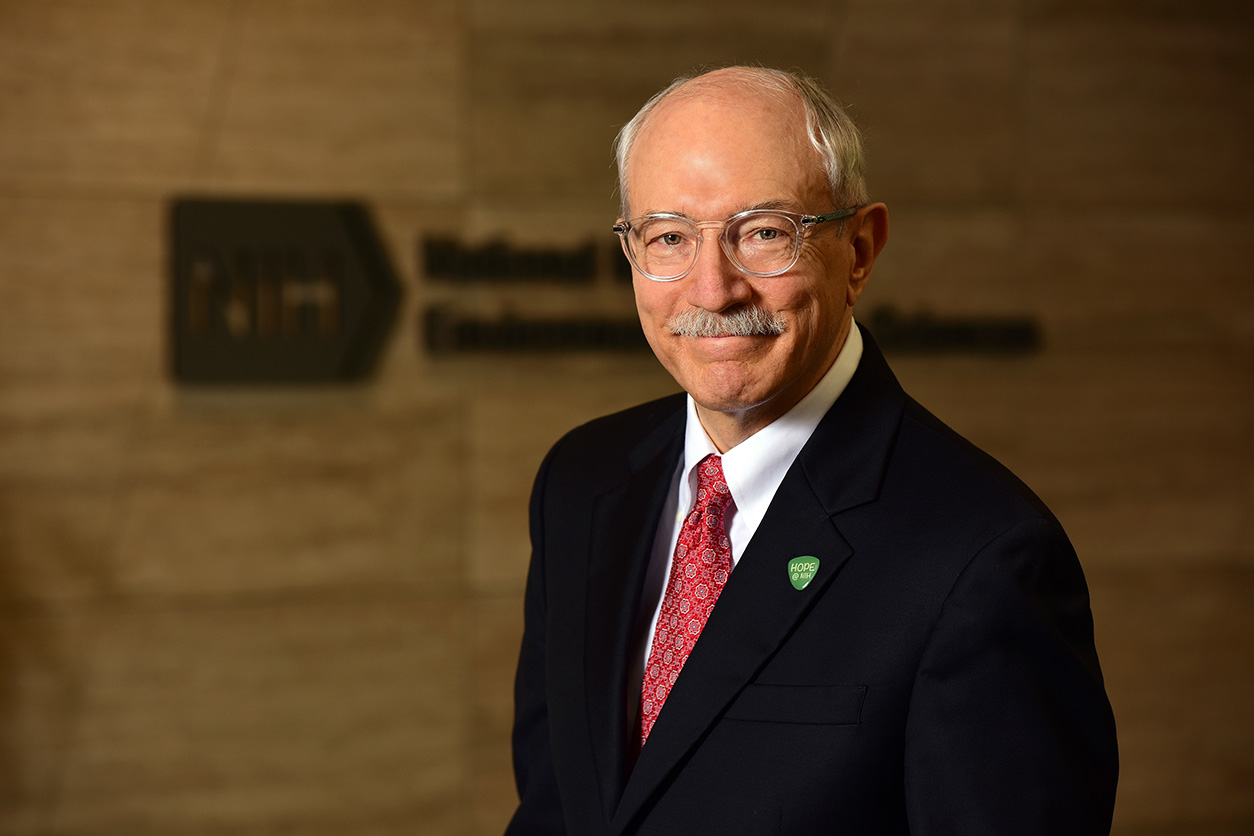

Rick Woychik, Ph.D., directs NIEHS and the National Toxicology Program. (Image courtesy of NIEHS)

Rick Woychik, Ph.D., directs NIEHS and the National Toxicology Program. (Image courtesy of NIEHS)When disaster strikes, whether due to wildfires, hurricanes, chemical spills, or other calamities, it is critical to understand effects on human health and the environment. Some concerns are grounded in short-term recovery and response efforts, involving questions about whether it is safe to breathe air or drink water in an affected neighborhood. Still other issues may reverberate years and even decades after a given event, such as how exposure to harmful agents, wildfire smoke, or severe mental stress affects our biology, potentially leading to ill health and disease.

Environmental health scientists can play a pivotal role in disaster response by increasing our understanding of potential health effects and building resiliency among affected communities. (Photo courtesy of PRESSLAB / Shutterstock.com)

Environmental health scientists can play a pivotal role in disaster response by increasing our understanding of potential health effects and building resiliency among affected communities. (Photo courtesy of PRESSLAB / Shutterstock.com)One of my goals as Director of NIEHS and the National Toxicology Program (NTP) is to increase scientific collaboration, and disaster research is an area where that is especially needed. In 2020, there were 22 weather- and climate-related disasters, each of which resulted in at least one billion dollars of damage, not including healthcare costs. That set the annual record and marked the sixth straight year that there were at least 10 such events.

To provide timely information to affected communities after a catastrophe, scientists need specialized resources and an infrastructure that promotes greater knowledge-sharing. The good news is that at NIEHS, our Disaster Research Response (DR2) program offers data collection tools, training, opportunities to engage local stakeholders, and guidance on best practices related to study protocols, among other support. And just last month, DR2 launched an online portal that includes more than 500 curated research tools and resources.

Recently, I spoke with Aubrey Miller, M.D., who directs DR2 and serves as NIEHS Senior Medical Advisor. He reflected on the history of the program, described some of the challenges and opportunities in this research area, and shared personal stories about his path to a public health career (see sidebar) as well as lessons learned along the way.

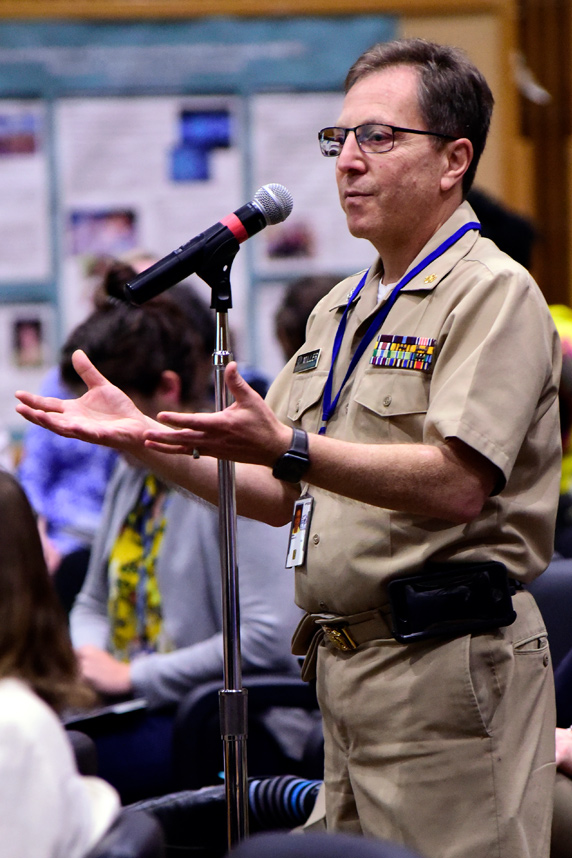

Miller has helped to coordinate large-scale responses to disasters and crises such as hurricanes, the H1N1 influenza pandemic, and the World Trade Center and anthrax attacks, among many others. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Miller has helped to coordinate large-scale responses to disasters and crises such as hurricanes, the H1N1 influenza pandemic, and the World Trade Center and anthrax attacks, among many others. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)Bringing researchers to the table

Rick Woychik: You joined NIEHS in 2010, three weeks before the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, 42 miles off the coast of Louisiana. Can you talk about the institute’s response and discuss some of your takeaways?

Aubrey Miller: What emerged from that spill was an amazing model highlighting NIEHS’s diverse programs and strengths for responding to disasters and other emergencies, and it helped to spur creation of the DR2 program.

The NIEHS extramural division teamed up with other NIH [National Institutes of Health] institutes to provide more than $25 million to academic centers at Gulf-area universities. Those centers then worked with affected communities to perform important studies to address their health concerns, such as the safety of the seafood and risks for pregnant women.

In addition, our intramural program developed the GuLF STUDY [Gulf Long-term Follow-up Study], which is tracking the health of 33,000 workers and volunteers who helped with various aspects of cleanup and recovery activities. Also, NTP conducted research in partnership with FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] and NIOSH [National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health] to help understand the toxicity of spill-related exposures. The NIEHS Worker Training Program provided vital health and safety education to almost 150,000 clean-up workers across the Gulf region.

Subsequently, NIEHS initiated the development of the DR2 program, which started as a pilot project in 2013, in collaboration with the National Library of Medicine. We received seed money from Dr. Francis Collins’s NIH Director’s Discretionary Fund after he and other officials called for improving research related to public health emergencies. NLM has been a DR2 partner from the beginning because they were developing important resources and access to scientific papers, technical reports, and other disaster-related information to advance the research. So, it made good sense for them to be a collaborator.

I learned that making progress in this space requires bringing the research community to the table. At NIEHS and across NIH, we have the best and brightest minds in the world, and if they're not part of the conversation and helping to respond to these situations, we’re missing a big piece of the puzzle.

DR2 also has contributed significantly to the COVID-19 research response, providing more than 120 scientific instruments and surveys to help advance the literature. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

DR2 also has contributed significantly to the COVID-19 research response, providing more than 120 scientific instruments and surveys to help advance the literature. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)Helping the most vulnerable

RW: Following one of these catastrophes, people may tend to think more about recovery and cleanup efforts, and less about the role science can play in mitigating harm. Can you talk about why research matters in disaster response?

AM: I can probably best answer that question with an example. Last year, wildfire season was especially intense, and I had a woman from California call with concerns. Her house had not burned down, but much of her neighborhood had. She had questions such as will my kids be safe, what about my pets, is the food growing in my garden still edible, and so forth. But we couldn't give her satisfactory answers because we don't yet have that science.

In the case of wildfires, part of the problem is understanding what the exposures are and what are the long-term effects. Also, many exposures involve mixtures, which further complicates matters. NIEHS and NTP scientists are working to understand complex mixtures, which continues to be increasingly important to answer these questions.

Given our changing climate and health emergencies such as COVID-19, it is clear that we need to create sound, deep science, and we need to bring together experts in exposure science, modeling science, epidemiology, and toxicology, to name just a few.

These issues are really close to my heart because I’ve personally worked with those devastated by hazardous exposures and disasters. In some cases, people not only lose their homes, but they also lose their communities. Through research and translation of that research, we can provide support to them in the short term, and in the long term we can strengthen our public health infrastructure and help our most vulnerable communities build resiliency before the next crisis hits.

Local control, federal support

RW: DR2 is all about empowering the research community to respond effectively to disasters and providing them with the resources to do so. But as you say, the program also is about sharing new scientific knowledge with stakeholders and the broader public. Can you expand on that aspect of your work, which scientists call translational research?

Miller, a retired Captain of the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, spoke with panelists at the 2018 NIEHS Global Environmental Health Day event. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Miller, a retired Captain of the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, spoke with panelists at the 2018 NIEHS Global Environmental Health Day event. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)AM: In 2015, we participated in a workshop in Houston that focused on what would happen if a hurricane hit the city. We shared some of the tools we had developed, such as the NIEHS RAPIDD, which stands for Rapid Acquisition of Pre- and Post-Incident Disaster Data. It is a research protocol that helps scientists reduce the time needed to collect health data, biological samples, and other critical information from people exposed to hazardous environmental agents. Many DR2 partners were there, and after we left, they kept working, and their relationships kept growing. Those efforts paid off two years later, when Hurricane Harvey ravaged Houston.

We went down there and brought together partners from the 2015 workshop, so we had academic centers collaborating with local health departments, emergency management groups, community organizations, and even NIEHS grantees from other parts of the country with expertise on exposures, the mental health effects of disasters, and so forth. They used the DR2 framework and research protocols to quickly unite with affected communities and initiate studies to help people and health agencies understand the exposures and risks at their homes and schools.

That experience showed that our research networks can be brought to bear on these events if we provide a platform, invite them in, and let them engage and do great work to translate science. Hurricane Harvey was a nice demonstration of local ownership with federal support, the opposite of a top-down approach, which never works in addressing the communities’ needs. For affected individuals and families, the issue is who's going to stay and help address their problems for the long haul, and that's the local folks.

Citation: Lurie N, Manolio T, Patterson AP, Collins F, Frieden T. 2013. Research as a part of public health emergency response. N Engl J Med 368(13):1251–5.

(Rick Woychik, Ph.D., directs NIEHS and the National Toxicology Program.)