NIEHS researchers and their collaborators found that mice from which the gene IRGM1 was removed developed an autoimmune disease that looked like Sjogren’s syndrome in humans. The mouse condition appeared to be caused by accumulation of defective mitochondria — energy-generating organelles in the cell — which activated the immune system. The team published their work Jan. 28 in the journal Nature Immunology.

The accumulation of defective mitochondria led to overproduction of an inflammatory protein called type 1 interferon. The findings suggest that failed quality control of mitochondria may cause Sjogren’s, lupus, and other autoimmune diseases through production of interferon.

Mouse model displayed autoimmunity

'Our studies show how mitochondrial DNA that is not removed activates the immune system in mice and how it may happen in humans,' said Fessler. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

'Our studies show how mitochondrial DNA that is not removed activates the immune system in mice and how it may happen in humans,' said Fessler. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)According to senior author Michael Fessler, M.D., many autoimmune diseases exhibit increased type 1 interferon. Fessler is head of the NIEHS Immunity, Inflammation, and Disease Laboratory, as well as the Clinical Investigation of Host Defense Group.

He added that small changes in the DNA code, called polymorphisms, in certain genes increase a person’s risk of developing autoimmune disease. One of these genes is IRGM — called IRGM1 in the mouse — which is required for autophagy. That process clears defective structures inside cells through a process similar to digestion.

One of Fessler’s collaborators had created a strain of mice lacking IRGM1 to study the gene’s role in fighting infections (see sidebar). Fessler noticed that the mice displayed an autoimmune condition that looked like Sjogren’s.

When team members checked the animals’ type 1 interferon levels, the mice, like Sjogren’s patients, had increased amounts of the protein. Fessler wondered if the inability to remove damaged mitochondria was driving the production of type 1 interferon.

'We speculated that if autophagy is deficient, then maybe autophagic clearance of mitochondria, called mitophagy, is also deficient,' Fessler said. 'If so, this might provide new hints into what happens in Sjogren’s syndrome.'

Mitochondria, descendants of pathogens

Mitochondria make energy for each cell to survive, but they originated from an unusual source. Fessler said they are descended from ancient bacteria that were co-opted by human cells long ago because they generated energy efficiently.

Since these bacteria would prompt an immune response, evolution led to them being surrounded with layers of membrane inside cells. Cloaked from the immune system, the bacteria — now mitochondria — are engaged in a symbiotic relationship with mankind.

However, mitochondria can sometimes become damaged, spilling their DNA and RNA into the interior of the cell, where immune sensors detect the molecules as foreign. The immune system reacts and turns on production of type 1 interferon, causing inflammation and autoimmunity.

'Interferon seems to play a crucial role in the severity of autoimmune conditions,' said Rai. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

'Interferon seems to play a crucial role in the severity of autoimmune conditions,' said Rai. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)'There is some evidence in lupus that mitochondrial DNA is increased and cannot be properly cleared,' said Prashant Rai, Ph.D., an NIEHS visiting fellow who works with Fessler and is the paper’s first author. 'When we genetically blocked interferon in the IRGM1 knockout mouse, we cured the Sjogren’s-like autoimmune disease.'

Tissue-specific triggers

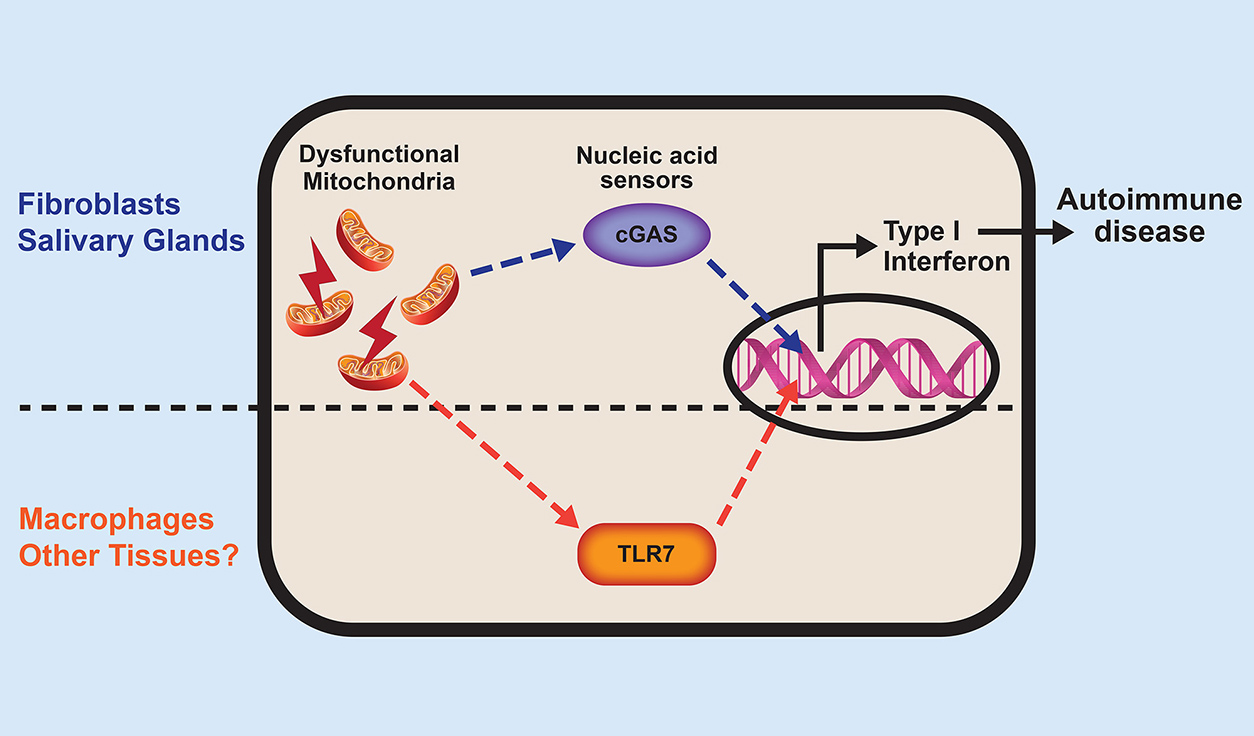

Fessler and Rai wanted to confirm whether leakage of mitochondrial DNA initiated an immune response the same way in every tissue. They tested two very different cell types: fibroblasts, which maintain connective tissue, and macrophages, specialized immune cells that eat harmful organisms.

The researchers saw a marked difference between the cells. In fibroblasts, leaking DNA activated an immune receptor called cGAS, but in macrophages, an RNA receptor known as TLR7 was activated, likely due to mitochondrial RNA.

'Both fibroblasts and macrophages made type 1 interferon, but the mechanism was different, suggesting that autoimmune diseases can affect different tissues in a selective manner,' Rai said.

In short, cGAS caused autoimmune damage in some organs of the IRGM1-deleted mouse, but not in others.

Citation: Rai P, Janardhan KS, Meacham J, Madenspacher JH, Lin WC, Karmaus PWF, Martinez J, Li QZ, Yan M, Zeng J, Grinstaff MW, Shirihai OS, Taylor GA, Fessler MB. 2021. IRGM1 links mitochondrial quality control to autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 22(3) 312–321. (Summary)

The nucleic acids — DNA and RNA — that spill out of broken mitochondria activate tissue-specific sensors, or receptors. These processes trigger type 1 interferon production and eventually autoimmune disease. (Illustration courtesy of Prashant Rai / NIEHS)