Artist Mallery Quetawki and NIEHS Superfund Research Program (SRP) scientists are turning complex environmental health concepts into meaningful images for Native American communities.

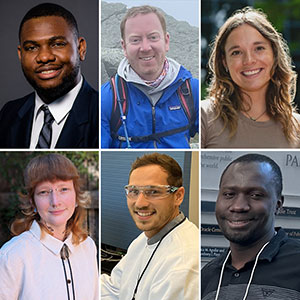

Quetawki is a member of Zuni Pueblo, an indigenous community in western New Mexico. She works with researchers at the University of New Mexico (UNM) SRP Center to increase environmental health literacy by bridging Western scientific concepts and traditional knowledge.

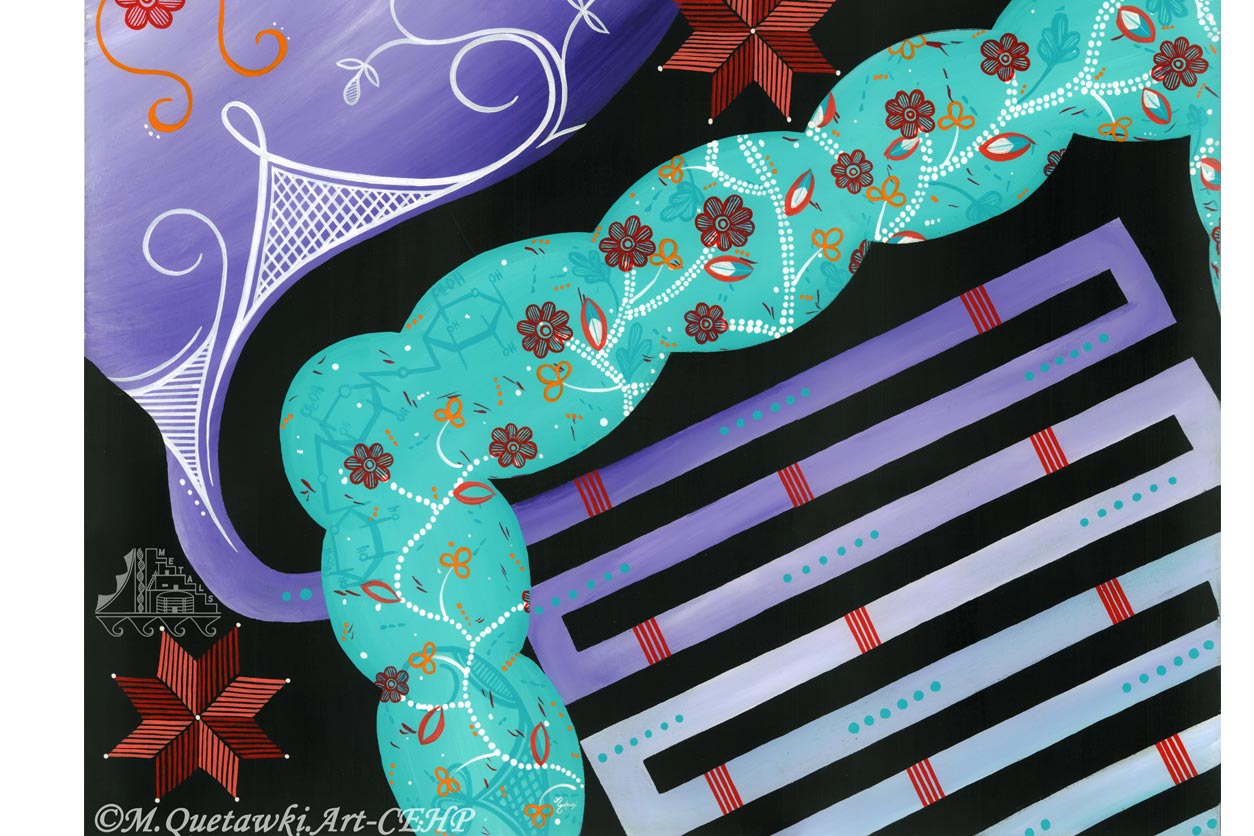

This painting explains that the gut microbiome is populated by diverse communities of bacteria that can change the environment of the digestive tract. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)

This painting explains that the gut microbiome is populated by diverse communities of bacteria that can change the environment of the digestive tract. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)“Scientific findings and terminology can be inaccessible to many of the people who are most affected by environmental exposures, due to inaccurate translation,” said SRP Health Specialist Brittany Trottier, who leads the program’s community engagement activities.

“It is exciting to see SRP teams moving research beyond the lab and into meaningful messages that communities can relate to and understand,” she added.

Quetawki’s artwork was featured on the cover of the June 2020 issue of the journal Maternal and Child Nutrition. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)

Quetawki’s artwork was featured on the cover of the June 2020 issue of the journal Maternal and Child Nutrition. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)Culturally relevant research translation

At the UNM SRP Center, researchers work alongside tribal partners to understand their environmental health concerns and how best to address them.

“I use art to help our Native communities understand concepts around environmental public health, especially individuals living in and around abandoned uranium mines,” Quetawki explained. “Many of these topics are complex, and some of the words do not exist in our indigenous languages. I help portray these ideas so that our relatives understand what is going on both in the environment and inside their bodies.”

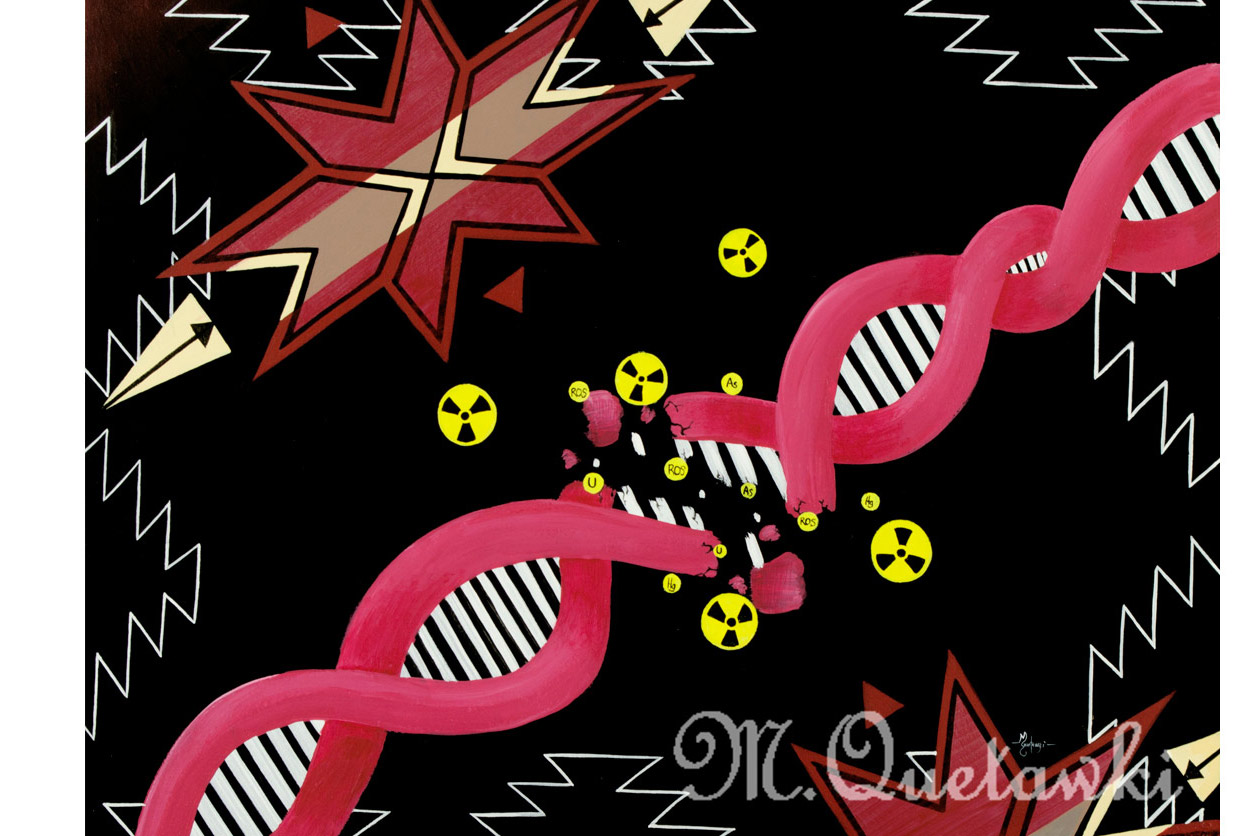

Using tribal symbolism, she creates intricate artwork to communicate how metals such as arsenic and uranium can damage DNA and the immune system.

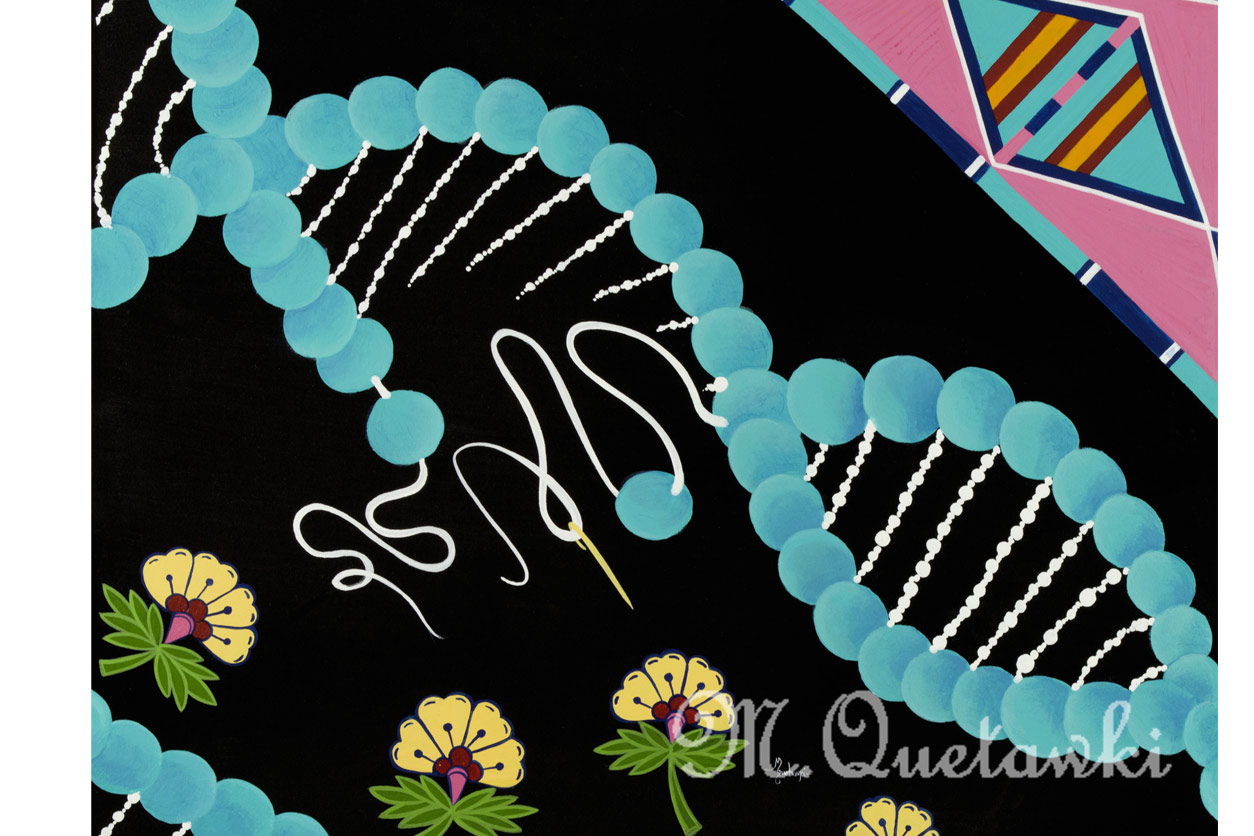

This image depicts how environmental contaminants cause damage to a strand of DNA. Background designs near edges of painting represent Pendleton blankets that are used in gift giving, trading, and traditional ceremonies. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)

This image depicts how environmental contaminants cause damage to a strand of DNA. Background designs near edges of painting represent Pendleton blankets that are used in gift giving, trading, and traditional ceremonies. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)She also developed paintings for participants in the Thinking Zinc clinical trial, which evaluates whether dietary zinc supplements can protect against metal exposure. Her painting compares DNA repair, aided by zinc, to the creation of beaded items in Native American culture.

“Quetawki’s approach demonstrates the importance of reporting back study findings to build trust and cooperation throughout the research process,” said Trottier.

Other art pieces by Quetawki explain the role of the immune system in protecting the body from environmental exposures and disease.

This image shows how the process of DNA repair, aided by zinc, is like restringing a traditional beaded necklace that is broken. The flower design symbolizes the idea of regrowth. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)

This image shows how the process of DNA repair, aided by zinc, is like restringing a traditional beaded necklace that is broken. The flower design symbolizes the idea of regrowth. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)COVID-19 response

Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, the team focused on creating artwork to communicate concepts such as masking and social distancing with tribes around the country.

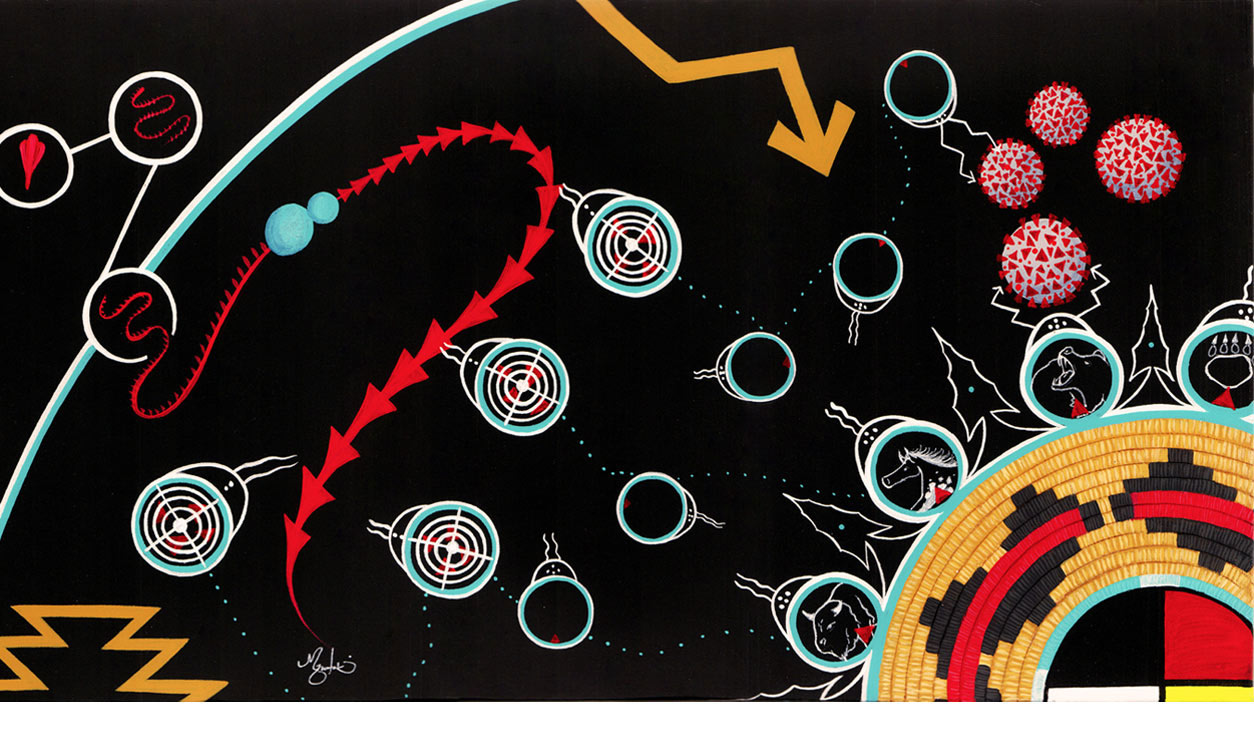

To promote COVID-19 vaccination among Native American communities, Quetawki created paintings to explain how mRNA, antibodies, and vaccines work. The art incorporates Zuni symbolism to show the human body’s natural defense mechanisms.

UNM SRP Center scientists and Quetawki are working to address tribal members’ concerns about COVID-19 vaccines. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)

UNM SRP Center scientists and Quetawki are working to address tribal members’ concerns about COVID-19 vaccines. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)“I’m interested in using art to promote health in our community, specifically using our cultural traditions, symbolism, and stories” said Quetawki. “By doing this, we are addressing the core values that come from our communities and providing a teaching tool.”

Art and public health intersect

UNM scientists and partners collaborate on a training program to increase participation in environmental health sciences research among Native American and Hispanic students in high school and college. Through that initiative, Quetawki leads workshops and discussions about using art as a tool for health and science communication.

Quetawki created artwork to fill in knowledge gaps regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, communicating the importance of wearing masks, washing hands, and getting tested. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)

Quetawki created artwork to fill in knowledge gaps regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, communicating the importance of wearing masks, washing hands, and getting tested. (Image courtesy of Mallery Quetawki)During the pandemic, she presented on the intersection of art and public health to several high school art classes and youth programs, and she hosted virtual art therapy painting classes.

Quetawki’s work has been featured by several museums, including a traveling exhibition by the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum of Contemporary Native Arts Exposure. Her art also has graced the covers of scientific journals such as Academic Medicine.

(Mali Velasco is a research and communication specialist for MDB Inc., a contractor for the NIEHS Superfund Research Program.)