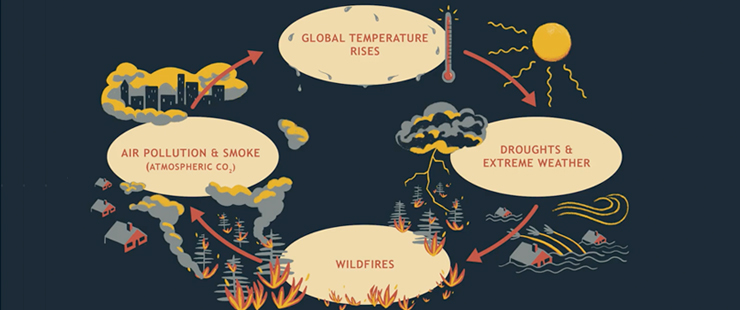

A warming planet brings drier vegetation, more lightning, and more wildfires. The typical three-month fire season now stretches to nearly a year, according to Toddi Steelman, Ph.D., dean of the Duke University Nicholas School of the Environment.

That new reality has grave implications for firefighters who now put themselves at risk year-round, she said. Steelman spoke July 23 at a lecture sponsored by the NIEHS Office of the Director.

Steelman explained that as humans, we are full of contradictions, such as wanting to live near wildlands and also wanting to be safe. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Steelman explained that as humans, we are full of contradictions, such as wanting to live near wildlands and also wanting to be safe. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)“Dr. Steelman’s talk was fascinating and highlighted many opportunities for intersections between NIEHS and Duke,” said Acting Chief of Staff Richard Kwok, Ph.D., who introduced Steelman. “Her talk highlights the important role of research in disaster preparedness and response, which has been a focus of NIEHS through our Disaster Research Response program [see sidebar].”

Effective work may be missed

Steelman, a social scientist and wildfire expert, has catalogued damaging wildfires from across the world. Between January and July 2019, more than 24,000 fires erupted in the U.S., burning more than 2.5 million acres. However, this has been a quieter fire season than the last two years, she noted. Ten-year averages for this time of the year are 41,524 fires and 4.7 million acres burned.

“We are incredibly effective as a fire-fighting community at putting out 93-98% of fires,” she said. “It is the 2-3% that we are not effective at putting out that command our attention, suck up all of our resources, and induce billions of dollars in damage.”

The July 2018 Skyline fire near Corona, California burned 250 acres before it was contained. (Photo courtesy of Tim Gray, Shutterstock.com)

The July 2018 Skyline fire near Corona, California burned 250 acres before it was contained. (Photo courtesy of Tim Gray, Shutterstock.com)A human tragedy

On June 28, 2013, Steelman and her team were concluding field work outside Prescott, Arizona. As they packed up to leave, a lightning strike ignited brush just over the mountains, near a town called Yarnell. The team flew home and woke up June 30 to the news that the fire overran and killed 19 members of the Granite County Hotshots.

Kwok co-leads a long-term health study, with Dale Sandler, Ph.D., and Larry Engel, Ph.D., (not shown), on oil spill clean-up workers and volunteers. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Kwok co-leads a long-term health study, with Dale Sandler, Ph.D., and Larry Engel, Ph.D., (not shown), on oil spill clean-up workers and volunteers. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)It was the largest single-day loss of firefighters since September 11, 2001, according to the National Fire Protection Association. Though significant attention focused on the decision-making in the days, hours, and minutes before the disaster, Steelman said it was a tragedy that was years in the making.

Setting the stage

To prove her point, Steelman gave a primer on recent trends in wildfires, starting in 1988 with the Yellowstone fires that burned a third of the national park. She explained how the history of fire suppression, the movement of people into areas prone to wildland fires, and increases in hot, dry, windy weather were leading to bigger, more dangerous, and faster moving fires.

“That is exactly what the Granite Mountain Hotshots were facing on their fateful day,” she said. “The fire was moving at 10-12 miles per hour — that is something you can’t outrun.”

The 2008 Sayre fire destroyed 489 residences in Los Angeles, California, the worst loss of homes due to fire in the city’s history. (Photo courtesy of Krista Kennell, Shutterstock.com)

The 2008 Sayre fire destroyed 489 residences in Los Angeles, California, the worst loss of homes due to fire in the city’s history. (Photo courtesy of Krista Kennell, Shutterstock.com)The big picture

According to Steelman, few people appreciate how trends at the global, national, and regional scales affect what happens at the local scale. She argued that scientists and policymakers need to work at all levels, through efforts like initiating international climate change relief and recognizing the limits of fire suppression, to change the trends.

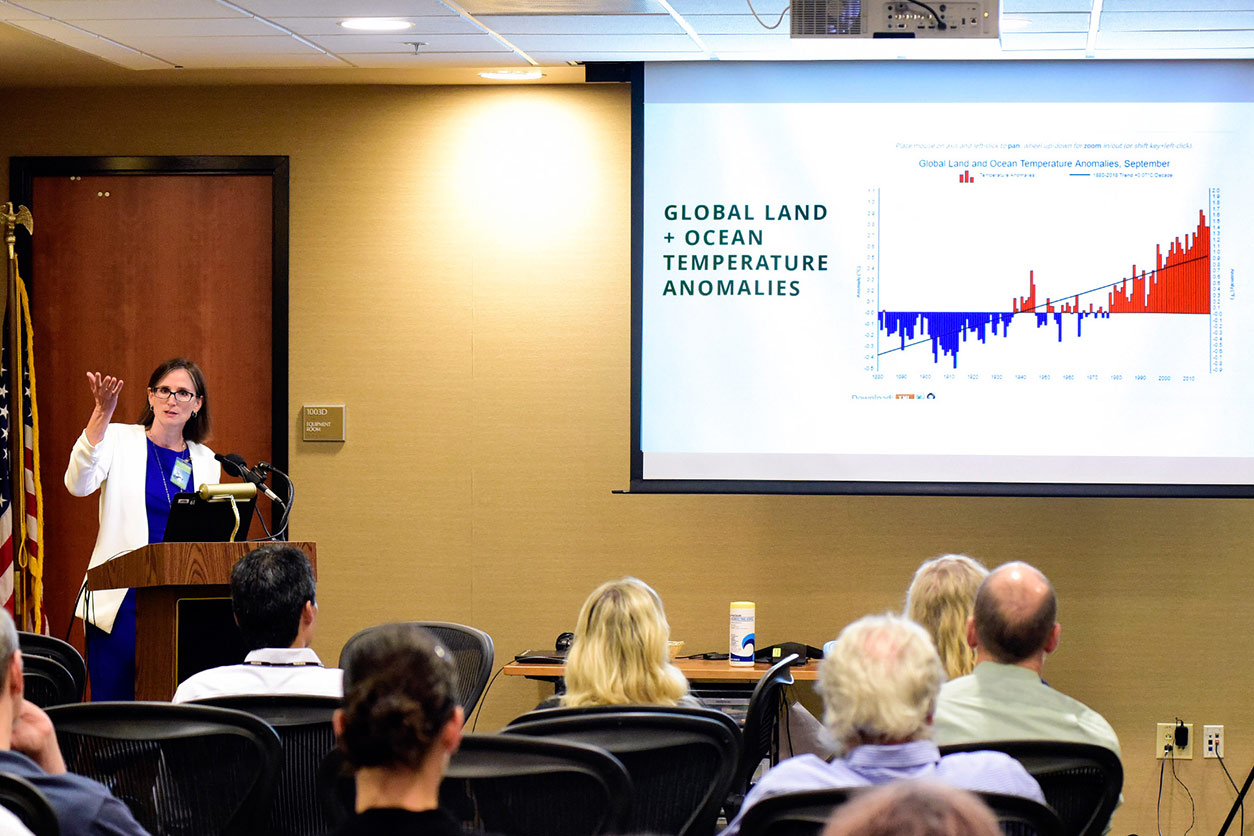

Steelman presented data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association showing increases in global land and ocean temperature for the last 500 months in a row. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Steelman presented data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association showing increases in global land and ocean temperature for the last 500 months in a row. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)In a discussion following the lecture, Trisha Castranio, an NIEHS program analyst in Global Environmental Health, asked how to foster resilience in the people and communities most likely to be affected by wildfires.

Steelman said it is important for firefighters to recognize they are one piece of a larger process that will unfold over a long period of time. “We have found that bringing expectations for success in line with what’s possible is important for the mental health issues faced by firefighters who are used to going out and being very effective in their job,” she added. “These aren’t your grandfather’s fires.”

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)