An innovative project called 'A Day in the Life' features Los Angeles-area youths telling stories and documenting air pollution levels where they live, go to school, work, and play.

The students, all from communities of color located near high-pollution areas, used a creative approach to visualizing data, which is known as a story map. The final project was released in December by the NIEHS-funded University of Southern California Environmental Health Centers Community Engagement Program on Health and Environment (CEPHE).

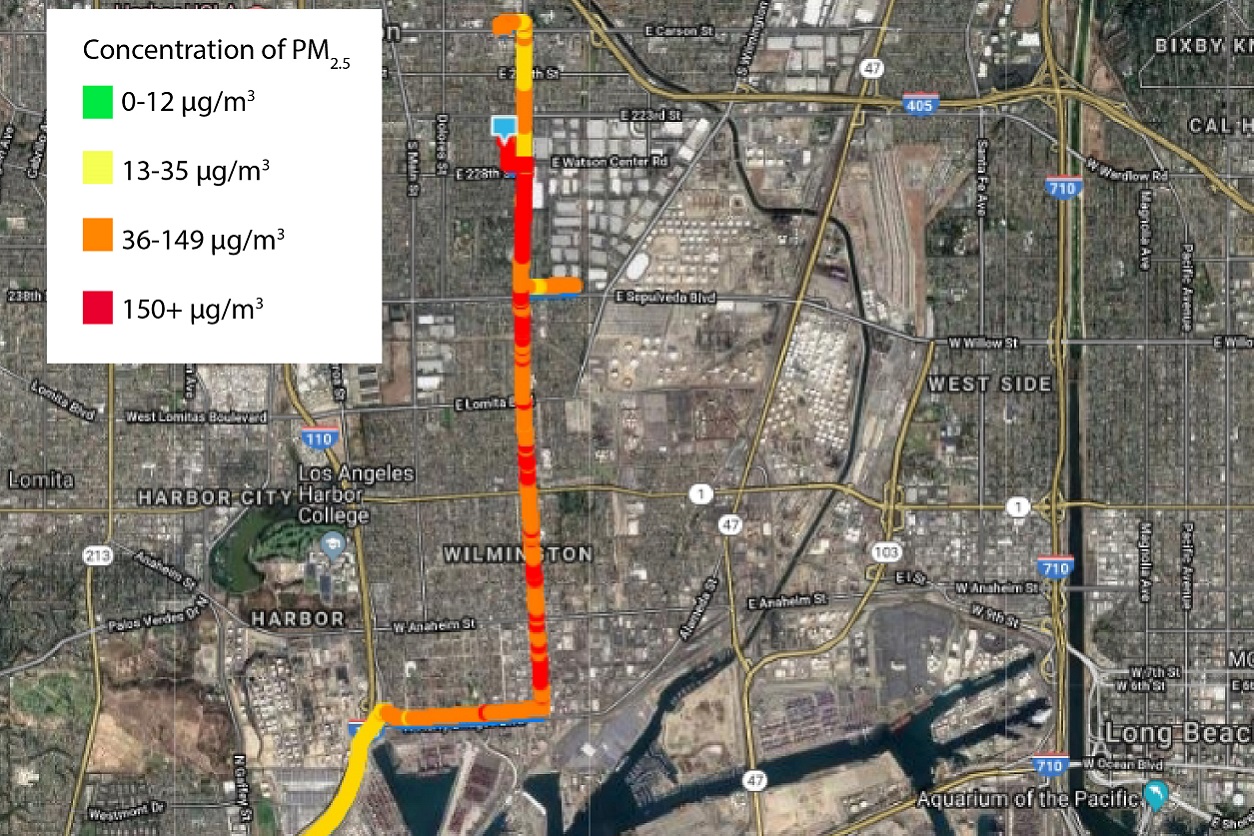

The map of a student named Isabel documenting her daily exposure to high levels of air pollution on her bus ride to school. (Photo courtesy of CEPHE)

The map of a student named Isabel documenting her daily exposure to high levels of air pollution on her bus ride to school. (Photo courtesy of CEPHE)CEPHE partnered with Communities for a Better Environment, South Central Youth Leadership Coalition, and Promoting Youth Advocacy/Asian and Pacific Islander Forward Movement.

'Air pollution across LA does not affect communities equally,' said Zully Juarez, community engagement project coordinator at CEPHE, explaining one aspect of environmental justice. 'The presence of freeways, industry, and oil refineries can worsen air quality around the high schools these students attend and places they hang out.'

Routes of exposure

CEPHE equipped each student with an a low-cost air monitor to measure fine particulate matter. The students went about their days, walking or riding a bus to school, attending classes, going to work, and spending time with friends.

Each student logged an average 22 hours of monitoring time, for a total of more than 400 hours of air quality data. The results were overlaid on maps and color-coded to show levels of particulate matter the students breathed.

CEPHE offered participants workshops and training about the health effects of poor air quality, and the students gained the skills to share their experiences.

'This creative program is helping youths visualize their exposures by providing them with the appropriate tools and training,' said Liam O’Fallon, director of the NIEHS Partnerships for Environmental Public Health.

Maps and motivation

The story maps document the students' experiences and motivations for joining the project. Many wrote that they were motivated by social injustices and disproportionate levels of illness in their communities.

'When you take a walk in the park, all you see is the refinery,' wrote a student named Ashley. 'People are aware of it, but they are not speaking up about it, so I wanted to focus on the parks because I feel it will open people's eyes to see how it is affecting kids, animals, and everyone.'

'These are [the] only two parks that are near my home… [T]he refineries are visible, and you can see the particulate matter in the air,” wrote CEPHE participant Ashley. Wilmington Waterfront Park is shown. (Photo by Ashley Solorio, courtesy of CEPHE)

'These are [the] only two parks that are near my home… [T]he refineries are visible, and you can see the particulate matter in the air,” wrote CEPHE participant Ashley. Wilmington Waterfront Park is shown. (Photo by Ashley Solorio, courtesy of CEPHE)Another student traced her bus route to school, measuring high particulate levels along most of the way. To her, the environmental justice issues that plague this part of LA are apparent, but often unaddressed.

'I breathe the toxins that go in and out of my body every day,' she wrote. 'Low-income communities not only face discrimination because of their skin, but they also face environmental racism.'

Building skills to collaborate

'This program provides structure to build environmental health literacy, technical skills, and collaboration between scientists, residents, and environmental justice organizations,' said Wendy Gutschow, CEPHE community engagement administrator. '[It] teaches youths that resources exist for them to study their environments, gives them the tools and knowledge to influence policy, and encourages them to be active in their communities.'

'Through this project, students can ask questions about their exposure levels and consider solutions,' said O'Fallon. 'It may even inspire them to study environmental health science in college.'

Gutschow said they want to continue the program with other local groups, and share documentation so it can be replicated elsewhere. 'Our hope is to identify ways this program can accommodate audiences other than high school youths, such as adults who are involved in a local environmental justice organization,' she said.

(Sheena Scruggs, Ph.D., is the Digital Outreach Coordinator in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)