Some neurobehavioral disorders — such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, and Tourette’s syndrome — are far more common in males than females. But why?

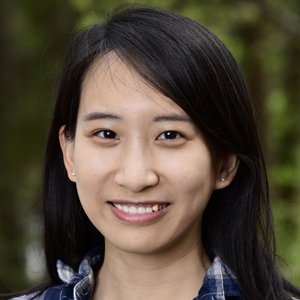

During her talk at NIEHS Sept. 24, grantee Marissa Sobolewski, Ph.D., explained that such disparity exists partly because males experience a testosterone surge early in life.

She noted that endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which mimic sex hormones, can intensify that surge and change the epigenetic profiles of males’ brains. Epigenetic changes, which are heritable, affect DNA function but not the underlying nucleotide sequence.

The big question Sobolewski seeks to answer is how disruption of early-life testosterone and brain epigenetics can increase males’ risk of developing one of these disorders.

Thaddeus Schug, Ph.D., a health scientist administrator in the institute’s Population Health Branch, hosted the talk as part of the Keystone Science Lecture Seminar Series.

Too much testosterone

“Hormones don't cause behavior,” Sobolewski said. “Instead, it's a more nuanced, causal relationship. Hormones change the probability that an organism will respond to an environmental stimulus in a particular way.” (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

“Hormones don't cause behavior,” Sobolewski said. “Instead, it's a more nuanced, causal relationship. Hormones change the probability that an organism will respond to an environmental stimulus in a particular way.” (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Sobolewski is a principal investigator at the University of Rochester Medical Center. “One of my favorite aspects of toxicology research is that we get to use [EDCs] to discover the basic science underlying the relationship between hormones and behavior across development,” she said.

Scientists have long known that males and females encounter different hormonal cues during early development, according to Sobolewski. Male mice, rats, and humans all experience a testosterone surge that starts in the womb and peaks after birth.

Less clear has been how major boosts in testosterone during development can increase males’ susceptibility to neurobehavioral disorders such as ADHD.

Chemical cocktail

Sobolewski’s laboratory exposed pregnant mice to a curated mixture of EDCs, including bisphenol A and perfluorooctanoic acid, which are found in many consumer and industrial products. That mixture resulted in significant increases in testosterone in male offspring but not in female offspring.

Those testosterone increases in turn disrupted endocrine processes that regulate reproductive and nervous systems, as well as other systems in the body. When Sobolewski’s team subjected the offspring to a battery of tests, they found that males demonstrated more severe behavioral problems than females.

Sobolewski shared videos from her laboratory in which male mice demonstrated attention deficits, greater impulsivity, and less sociability.

“Marissa has developed some very creative tools to investigate the effects of chemical mixtures on sex, development, and behavior,” said Schug. “Her research demonstrates the important biological role sex differences play in the origins of disease.

Schug oversees programs in male and female reproduction, metabolism, development and disruption of the endocrine system, and cardiovascular health. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Schug oversees programs in male and female reproduction, metabolism, development and disruption of the endocrine system, and cardiovascular health. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Observing chimps in Uganda

Sobolewski says that her research is influenced in part by her early-career work studying chimpanzees in the forests of Uganda.

There, she took advantage of the fact that circulating steroid hormones appear in urine about two to four hours after they are produced. She observed chimps as they engaged in aggressive acts such as killing a neighboring rival and then collected their urine, finding increased levels of the hormones cortisol and testosterone.

“But after spending over two years collecting 3,000 urine samples … I was left a little bit wanting,” said Sobolewski. “All my studies had been correlations, when what I wanted to show was causation. That’s when I found a love for toxicology.”

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)