The impact of pollution on human health took center stage Nov. 26 as the NIEHS Office of the Director hosted three distinguished speakers for presentations and a workshop.

The issue is particularly critical because pollution kills three times more people than AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined, according to John Balbus, M.D., NIEHS senior advisor for public health. Yet those diseases receive the lion’s share of investment in global health.

Balbus introduced the three distinguished speakers to a gathering of NIEHS researchers and leadership. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Balbus introduced the three distinguished speakers to a gathering of NIEHS researchers and leadership. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Richard Fuller, Phil Landrigan, M.D., and Howard Hu, M.D., Sc.D., shared their visions for global research efforts. They suggested expanding the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation’s Global Burden of Disease Report to better capture environmental risk factors and to raise the visibility of the societal burdens of pollution-related disease and death.

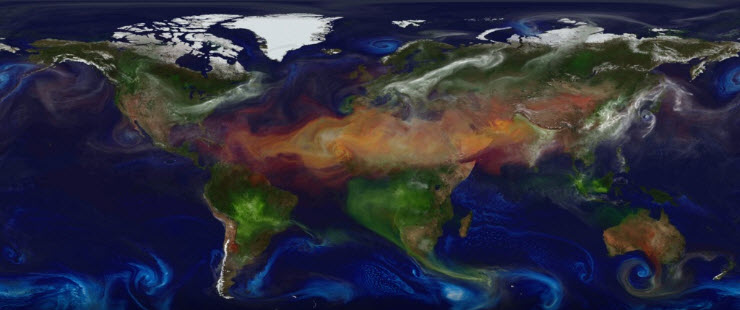

Pollution knows no boundaries

Pollution is the leading cause of death around the globe, said Fuller, president of the international nonprofit Pure Earth and co-chair of the seminal Lancet Commission report on pollution and health. The 2017 report blamed pollution for more than 9 million deaths, warning that it “endangers the stability of the Earth’s support systems and threatens the continuing survival of human societies.”

Fuller said the Global Alliance on Health and Pollution is a group of more than 65 leading institutions and governments working together to address the pollution crisis. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Fuller said the Global Alliance on Health and Pollution is a group of more than 65 leading institutions and governments working together to address the pollution crisis. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)Although nearly 92 percent of pollution-related deaths occur in poor countries, wealthier regions do not escape unscathed, said Fuller, because pollution spreads around the world. He presented other sobering statistics. He noted that 29 percent of shellfish consumed in the U.S. comes from China. In 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was able to test 0.10 percent of imports. Of that, about 9.5 percent was rejected due to heavy metals and antibiotic residues.

“There is great evidence of arsenic showing up in baby cereal, there is cadmium in other foods, there is lead all through the system,” said Fuller. He is working to highlight pollution as something that demands global attention.

Good news — a solvable problem

Landrigan stressed that pollution control can be cost-effective. “The control of ambient air pollution in the United States has yielded about $30 in benefits for every $1 invested,” he said. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Landrigan stressed that pollution control can be cost-effective. “The control of ambient air pollution in the United States has yielded about $30 in benefits for every $1 invested,” he said. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)The good news, said Landrigan, who co-led the Lancet Commission, is that pollution is a solvable problem. He directs Boston College’s Global Observatory on Pollution and Health, launched in September 2018.

“We hope … that this body of evidence will stimulate ministries of government, ministries of public health, and ministries of finance to invest resources in pollution control, all of which is good for global public health,” said Landrigan.

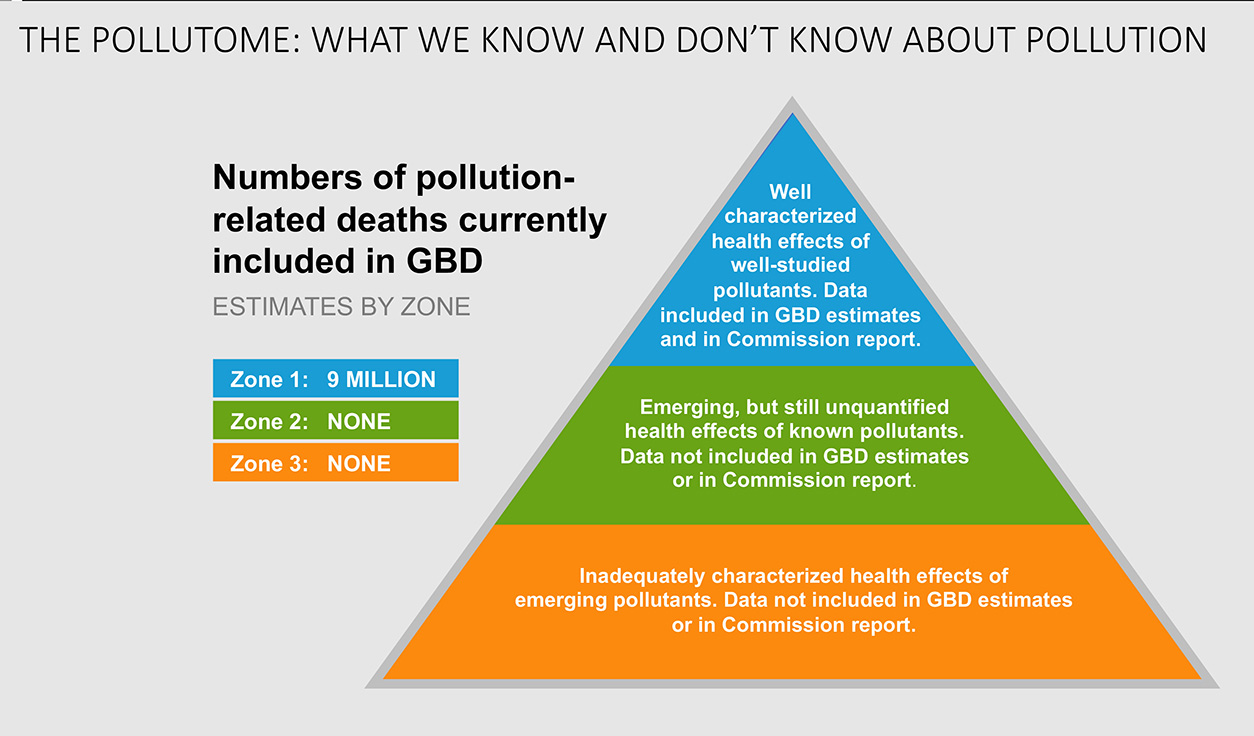

The pollutome — visualizing the unknown

The main challenge, he cautioned, is that the burden of disease attributed to pollution has always been undercounted. So he and his colleagues coined the word “pollutome” to cover all forms of pollution that have the potential to harm human health.

Linda Birnbaum, Ph.D., director of NIEHS and the National Toxicology Program, and others discussed communication needs around the health impacts of pollution and climate change. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Linda Birnbaum, Ph.D., director of NIEHS and the National Toxicology Program, and others discussed communication needs around the health impacts of pollution and climate change. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)The pollutome looks like a food pyramid gone awry. Divided into three zones, the tip of the pyramid, or Zone 1, contains the well-characterized health effects of well-studied pollutants. This is the source of the data on which the estimate of 9 million premature deaths is based.

Zones 2 and 3 include the unknown. Zone 2 holds the emerging, unquantified effects of known pollutants. Zone 3 covers inadequately characterized health effects of emerging pollutants.

The true burden of pollution

Hu, from the University of Washington, is leading an effort to quantify deaths due to these uncharted zones. He envisions a Pollution and Health Initiative as part of the Global Burden of Disease study, which involves a collaboration of more than 3,000 researchers in 140 countries and 3 territories.

Hu suggested that actual exposures exceed estimates in the Global Burden of Disease study, for reasons such as missing hot spots and imbalance in data from urban versus rural areas. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)

Hu suggested that actual exposures exceed estimates in the Global Burden of Disease study, for reasons such as missing hot spots and imbalance in data from urban versus rural areas. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw)“We are looking at years of life lost due to premature mortality, years lived with disability, disability-adjusted life years, healthy life expectancy,” Hu explained. “Our goal is to ultimately help clarify the true burden of pollution, thereby raising prevention and associated policies as a societal priority in all countries.”

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)